Economics 101 For the Political Junkie: Part 2 - Microeconomics - The Foundation Of All Economic Theory

CLASSICAL ECONOMICS

AS DEVELOPED IN PART 1, classical economics was the first attempt to explain why a relatively free economy worked the way it did. Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and John Stuart Mill were central in coming up with and then expanding on the initial ideas of economic theory. Adam Smith kicked things off with his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. From there, other thinkers expanded on or offered alternative ideas thereby fleshing out this new field of economic theory. The term "classical economics", by the way, was actually coined by Karl Marx in describing Ricardo's and Mill's version of economic theory, but it soon encompassed all of the related hypothesis.

One of the principal thoughts underlying classical economics is that a free market, unencumbered by government interference, will regulate itself; Smith's supposition was that an "Invisible Hand" will guide markets toward a state of natural "equilibrium"; a central argument made by political junkies, political pundits, and economists today. What Adam Smith posited, just as the feudal system was breaking down and the industrial revolution just beginning, was that national income was produced by labour, land, and capital. Further, with property rights to land and capital being held more and more by individuals rather than feudal lords or a king, the national income would be divided up between labourers, landlords, and capitalists in the form of wages, rent, and interest or profits.

From this followed the proposition of supply and demand, the underpinning of microeconomics, which applied to both the acquisition of goods and services as well as to labor. Under classical economics, the following assumptions are asserted:

- Supply creates its own demand - that is, aggregate production will generate an income sufficient enough to purchase all the output produced (Say's Law)

- Aggregate national savings must equal aggregate national investment and this equilibrium is maintained through flexible interest rates.

- Prices for goods and wages are flexible, moving up and down according to market forces

For the most part, it is the battle over these three assumptions that make economics so volatile and therefore interesting. Changing one, two, or all three assumptions leads us down paths to sometimes diametrically opposed economic theories.

JEAN-BAPTISTE SAY

BUILD IT, AND THEY WILL COME - SAYS :LAW

USING THE ABOVE ASSUMPTIONS and combining them with other observations, the field of microeconomics emerged. We will start our investigation by looking briefly at Say's Law, named after Jean-Baptiste Say, 1767 - 1832. He postulated the fundamental idea that supports sound-bite names like "supply-side" and "trickle-down" economics. Say holds that in any free market economy, the aggregate amount of product produced will produce sufficient income in wages to allow the aggregate demand to consume 100% of all that was produced. This then, would generate the demand needed to keep production and full employment moving right along, where full employment is the natural constraint on how much can be produced. In short, supply drives demand, a basic premise of classical and neo-classical economics. This idea held until John Maynard Keynes and his peers entered the picture to propose theories that turned this idea on its head by arguing that demand drives supply.

IF YOU SAVE, THEY WILL BUILD

YOU MIGHT START NOTICING the linkages between various economic activities that might have seem disconnected at first glance. My sub-title is a cute way of saying "aggregate national savings must equal aggregate national investment". Now this idea becomes much more complex when you bring in foreign trade and deficit spending, but let's leave it at personal and institutional savings at the moment.

The idea behind this second major assumption (these are not really assumptions by the way, there is a lot of mathematical analyses to back them up) is that money used for investing in the production of goods comes from savings of individuals or institutions. Where else can it come from? All other money in the economy is in circulation being used to buy goods, services, and labor. When circulating money comes to rest and is waiting to be used for something, that is basically your pool of savings from which investors can draw upon to borrow; this includes a person borrowing from his or her own savings to start a personal business.

Classical, neo-classical, and Keynesian economists all agree on the above points. They all also agree that the amount of savings will come into equilibrium with the amount of investment in an economy. For example, if an economy initially has $1 trillion in savings and $0 in investment, at some point in the future that ratio will change such that there are $500 billion in savings and $500 billion in investment. It is how this happens where the three economic systems disagree; in the case of classical economics, Smith et. al., believed flexible interest rates were responsible for this equilibrium.

The idea is simple. As savings increase, interest rates decrease making the cost of borrowing lower. This in turn will incentivize investment. As investment increases, interest rates increase thereby making it more advantageous to save; classic supply and demand. When the dust settles therefore, half the money is being saved and the other half is being invested.

THE LAW OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND

IF I DEMAND A LOT, I WILL PAY A LOT

THE THIRD MAJOR PREMISE OF THE CLASSICAL SCHOOL, as well as all other economic theories is that Prices are flexible; that prices of goods, services, and wages will vary based on market forces. Again, it is the characteristics of this flexibility that come under debate depending upon which economic system you are considering. Classical and, to a large extent, neo-classical economists believe that prices generally move smoothly with changes in supply and demand. Further, differing assumptions as to the relative "smoothness" of price changes lead to substantially different conclusions regarding outcome of economic activity.

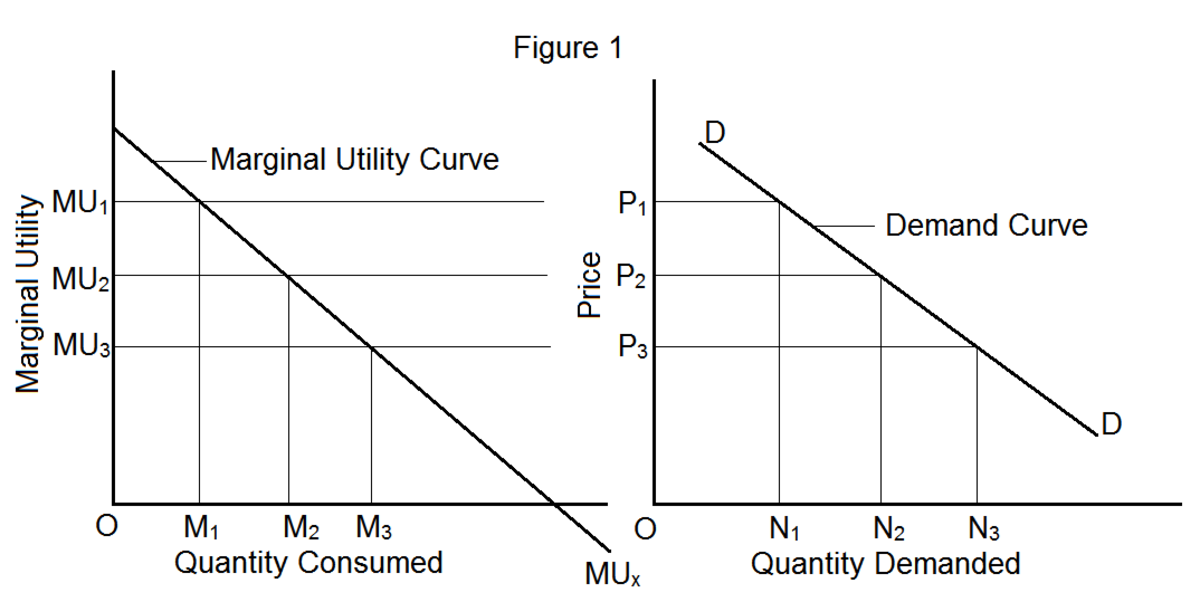

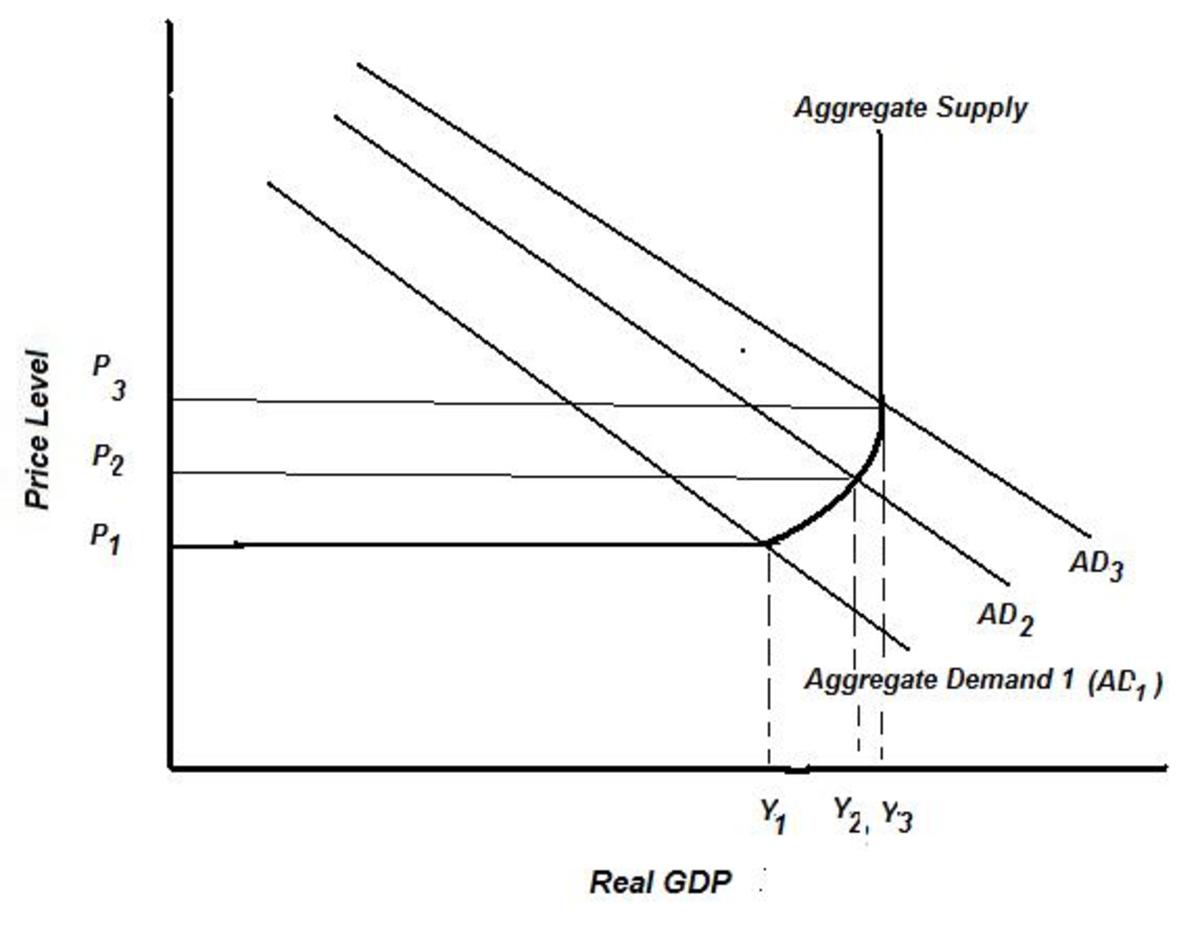

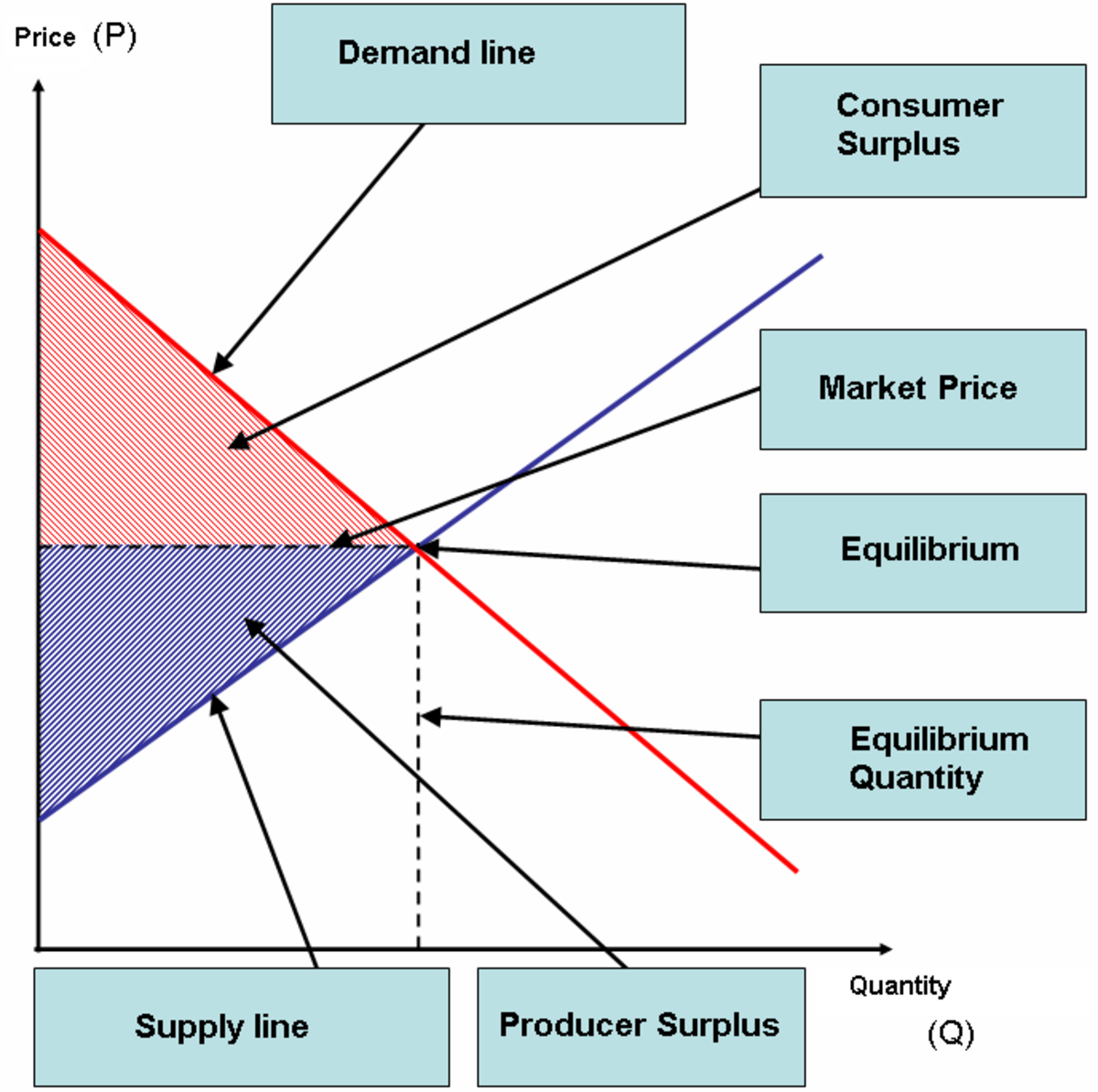

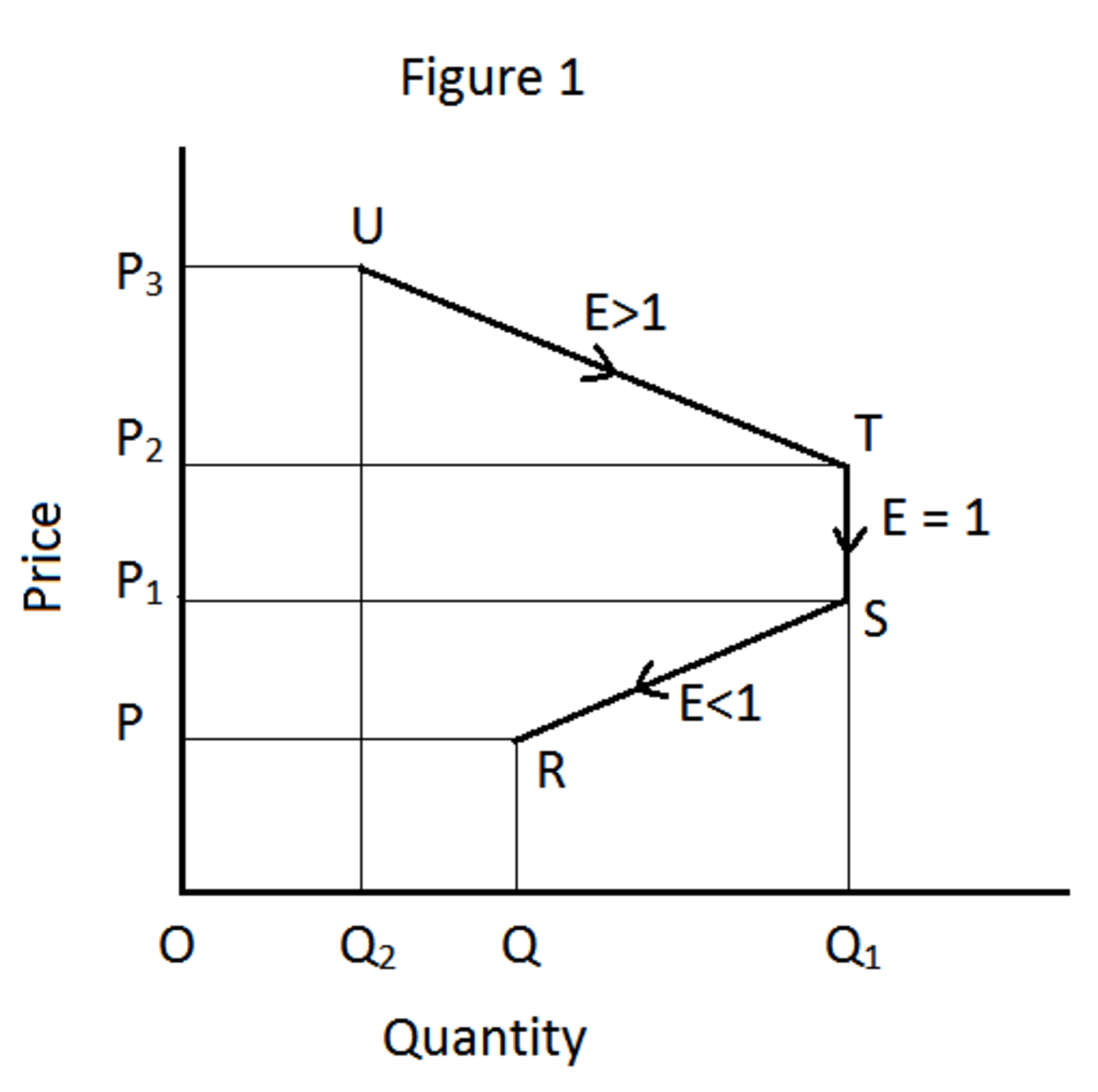

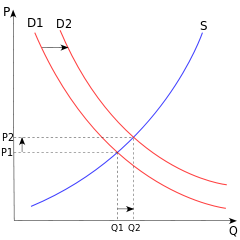

Here, however, we will just consider the basics of supply and demand, the heart of microeconomics. First, consider curve D1 on Chart 1; that is a "Demand Curve". It plots each point where consumers are willing to purchase quantity Q of product A if the price is P; as the price of product A falls, consumers are willing to buy more.

Now consider curve S, this is a "Supply Curve". Like the demand curve, it plots the quantity Q of product A the producer is willing to produce at price P. Similar to demand, as the consumer is willing to pay more for product A, the producer is willing to produce more. Where the demand curve D1 and the supply curve S meet, is the point of equilibrium that economist of all stripes say prices tend toward.

Let's complicate things slightly and tell you that the producer put on a major advertising campaign about product A, and it worked. The public became wildly enthusiastic and demanded a lot of product A. As a result, the consumer is willing to buy more of product A at every price level. This state of affairs "shifts" the demand curve to the right such that demand now follows demand curve D2; resulting in a new equilibrium point at a higher price, P, and quantity, Q.

NEO-CLASSICAL (FRESHWATER) ECONOMICS

NEO-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS MOVES ECONOMIC THEORY further down the road into esotericism. Some say neo-classisim arose with Alfred Marshall (26 July 1842 – 13 July 1924) and his book/text, Principles of Economics (1890); Marshall appears to be the Adam Smith of neo-classical economics. With his book, he ushered in the ideas like marginal utility and synthesized supply and demand, marginal utility, and costs of production into a single, unified idea.

The new ideas brought into economic theory by Marshall and many others are the following:

- People have rational preferences among outcomes that can be identified and associated with a value.

- Individuals maximize utility and firms maximize profits.

- People act independently on the basis of full and relevant information.

The thrust of these three maxims is a departure from classical economics in that it shifts the focus of the valuation of products from being based largely on "cost of production", as Smith and Ricardo suggest, to relative values placed on competing goods by the consumer; this is a fundamental shift. Those terms above, rational preferences, utility, and information coupled with the three assertions from classical economics form the underpinning of microeconomic theory.

ALFRED MARSHAL - THE BEGINNING OF THE NEO-CLASSICAL REVOLUTION

MICROECONOMICS

WIKIPEDIA DEFINES MICROECONOMICS as

"Microeconomics (from Greek prefix micro- "μικρό" meaning "small" + "economics"- "οικονομια") is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individual households and firms in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources."

From this simple idea flow a cornucopia of theories and schools to try to explain why the economy acts in the way it does under various external environments.

For example, you have the "theory of the firm" to describe profit maximization, and the derivation of demand curves leads to an understanding of consumer goods, while similarly the supply curve allows an analysis of the factors of production. Supporting the theories surrounding consumption, demand, and supply is the theory of "Utility maximization". Further, microeconomics is also about the theories that explain why supply and demand for a good or for an economy tends toward an equilibrium state as well as the factors which determine each; and so it goes.

So, how are all these ideas connected, as Marshall suggests? Well, from Chart 1 above you have already seen how two of them, supply and demand are related. If you believe the classical and neo-classical economists, suppliers produce goods which pay wages to labor which, in turn, creates demand for goods. How much is demanded is based on the Price of the good. If your a classical economist, the Price set by the "cost of production". Under neo-classical economics, however, it is the relative merit or "marginal utility" that consumers give one good over another (or not having it at all) that determines Price.

Price and Quantity are related in two ways, as we have seen, and they work in opposite directions depending on whether you are talking about demand or supply. On the Demand side, it is pretty simply. Demand for a good is the distribution of the quantity of a good that consumers are willing to purchase at a given price. It is a distribution since not all consumers act alike and therefore some may be willing to buy a good at a higher price than others simply because it represents a higher marginal utility to them, while others will buy something else or forgo the purchase altogether.

The idea behind marginal utility is not about cost but, instead, a goods perceived value, which, in turn, leads to some strange scenarios that on their face appear to be non-rational; remember that "rationality" is one of the three tenets of the neo-classical system. For example, the only thing holding me back from buying a $35,000 Nissan Leaf all-electric car is my wife. Here, an all-electric car has high utility for me but low utility for her and, of course, she is the wife; I lose. On the other hand, I will forgo buying a $2 bottle of soda pop in an airport because I think that is too expensive for that product; I would pay $1.50 however. Others, on the other hand, may pay $2.50. It is the number of people and quantity of soda pop each will buy at their respective price levels that produce the demand curve for soda pop. Likewise, you make decisions like this almost every moment of your life in some fashion or another and the aggregation of these decisions for a product or for an economy leads to that simple looking Demand Curve.

Similarly, there are many factors behind the decision to supply a certain quantity of a product. Probably the first thing to consider is if the maximum reasonable price consumers might pay times the total quantity they are willing to purchase at that price will cover the fixed costs of production. Fixed costs are those costs that don't change based on the number of things produced, e.g., the lease on the production facility. Say it is $10,000/month; well, it will be that amount whether you make zero units or make a million; it is fixed in the short-term. Therefore, if the maximum reasonable price doesn't cover fixed costs, no product will be produced.

The next thing that might be considered is profit margin. Profit margin, or, more specifically, net return on investment (ROI) is how much $1 invested earned at the end of the day. It might be, for example, 3% in a very high volume business like grocery stores or 10% in some defense industry programs, where volume is much lower, or 25% in new growth companies. The idea is that you set your internal goal, or internal rate of return (IRR), a related number, and if the price you are getting for a product doesn't generate this rate, you stop production for it is not worth your while to produce it. Why? Because you can find better alternatives to invest your $1 that will return the rate you want.

THE FOUNDERS OF THE AUSTRIAN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS

AUSTRIAN NEO-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS

NOW, THERE ARE VOLUMES UPON VOLUMES, of high level mathematics that goes on behind the scenes to support each of these ideas, unless you are from the Austrian School of neo-classical economics. The Austrians reject the use of models, econometrics, and the like being used to describe economic systems because they claim this approach doesn't model reality very well. Austrians, instead, believe the mechanics of the economy can best be undestood better if you consider it in subjective human terms rather than by objective numeric analyses.

From Wikipedia - "The Austrian School [think of Rep. Ron Paul] follows an approach, termed methodological individualism, a version of which was codified by Ludwig von Mises and termed "praxeology" in his book published in English as Human Action in 1949. Mises argued against the use of probabilities in economic models. Instead, his praxeological method is based on deductive arguments from what are considered undeniable, self-evident axioms, or irrefutable facts, about human existence."

From this, Mises asserts that this kind of reasoning can yield conclusions which could not be discovered by empirical observation or statistical inference.

Even so, the Austrian's accept, in fact even developed some of, the fundamental factors that that make up microeconomics, e.g. supply and demand curves, opportunity costs (Austrian idea), interest rates, capital costs and the like. How Austrian economists believe these and other factors influence economic activity, however, differ significantly with the mainstream neo-classic counterparts. We will discuss these differences at another time.

TIME FOR REHEARSAL

I HAVE PREVIOUSLY OFFERED UP THE DEFINITION OF MICROECONOMICS as being "a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individual households and firms in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources." How does what we have discussed support this definition?

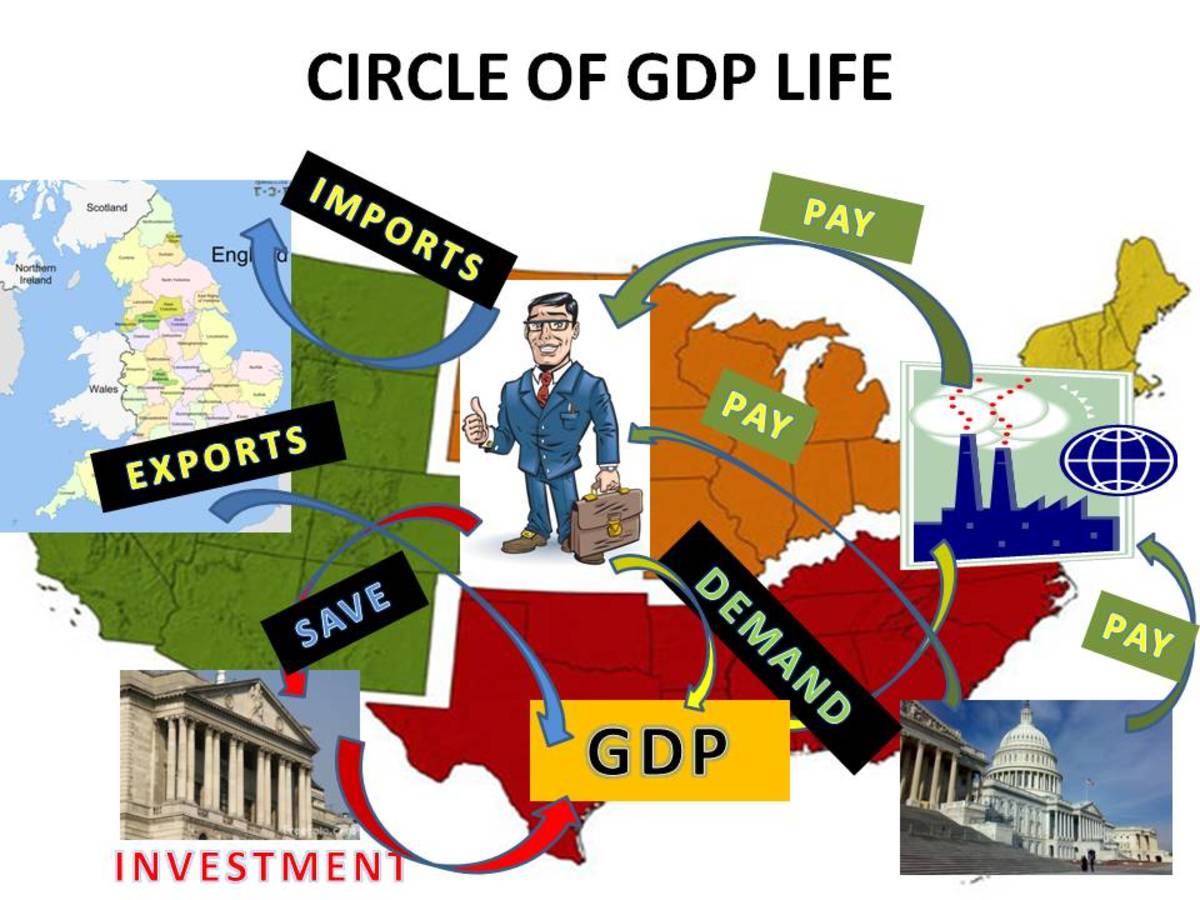

Let's consider the firm first, since classical and neo-classical economists believe supply drives demand; Keynesian's believe it is the other way around, but we haven't talked about them yet. An individual firm makes an estimation of saleability of a product and, if deemed profitable, produces it. To do that, the firm will borrow money either from themselves or others, if the interest rate savers are willing to accept is low enough, to buy the resources, including the labor needed for production. From the sale of the product the profits are either returned to company savings, to be used again, or distributed as profits which may end up as demand or savings. In the process workers are paid wages, some of which may be used to buy the product the firm made. In an extremely simple sense, that is a firm's economic cycle, if I may be so bold.

Embedded in this simplistic cycle are the individual decisions firms make in order to decide how much, Quantity, if any, of a product to produce and what Price to sell it at. In coming to such decisions, the "factors of production" are considered; factors such as cost of goods sold, cost of capital, fixed costs, opportunity costs and many others. It is both an objective and subjective exercise in decision making where some are successful at it and many are not, but in total for a product or products, the result is the Supply Curve.

On the flip side are household decisions regarding resource allocation. Here the decision-making process is much simpler, but, at the same time, much more personal and emotional. Classical and neo-classical economic theory relies on households, i. e., consumers, making rational decisions most of the time and not becoming caught-up in an emotionally motivated herd-mentality;' a state which can turn an economy on its head. However, if a consumer does make rational, self-serving, comparative decisions, then the economy can move along in a somewhat predictable manner.

Once again, trying keeping things a basic as possible, we can look at what choices households can make. To start with, what to do with the money which they receive in wages and other sources. There are two fundamental uses for this money; saving or spending. If it is saved, that provides a source of funds for entrepreneurs and firms to invest. If spent, that creates demand.

What would motivate consumers to save? One incentive is interest rates; if borrowers are willing to pay a high enough interest, then households may be willing to save. But, that is "may" be willing. Saving money must compete with the desire to acquire something you must have or desire to have.

How about spending, why do households spend? I would think survival would be the first answer; after that creature comforts. The selection of goods and services that fill these two requirements are relatively limited and decisions to purchase them should be pretty predictable making the Quantity demanded not all that difficult to figure out. Likewise, the Price consumers are willing to pay for these commodities is fairly "elastic", meaning they will pay about any price to acquire the necessities of life.

On the other hand, the huge market of goods and services people would "like to have" show a lot more "inelasticity" in Prices, making it much more of a challenge for suppliers to make their decisions. It is in this realm where I think the idea of "marginal utility" comes to the forefront, because not only are there choices between similar products, there are also choices between dissimilar commodities which have equal utility, or the choice not to purchase at all. The aggregation of all these decisions for a product or products create the Demand Curve.

From here, the war is on between Supply and Demand, each trying to guess what the other is going to do. Over time, in a stable economy, consumers and suppliers will come to a mutual understanding of the Quantity and Price goods should be produced and sold at. Obviously. things are never quite stable and perturbations keep occurring, but the tendency is to settle back toward the equilibrium point unless there has been either a "shift" in demand that increases or decreases demand at all Price levels, or a "shift" in Supply, normally caused by changes in technology that make production cheaper. That folks, for the time being, is microeconomics in a nutshell.

This article is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. Content is for informational or entertainment purposes only and does not substitute for personal counsel or professional advice in business, financial, legal, or technical matters.

© 2012 Scott Belford