Glimpses of Feminism in India

Questions Raised

It is difficult to theorize gender as much as about any form of knowledge because all theories are themselves paradigm laden and far from neutral.

“... the connection between women and knowledge about them is a result, struggled for, renegotiated and learned anew.” - ( Mary John)

In the beginning, it is important to understand the concepts of gender and sex. Gender is a socially constructed tool used to categorize humans based on sex, while sex is the biological categorization of the variants within the same species on the basis of their genetic composition.

The biological differences between man and woman (sexes) are quite ambiguous and do not suggest polarization but the concept of polarization is true of gender differences (social).

Although two X chromosomes of a woman compared to the tiny Y chromosome of a man indicate the biological superiority of women over men, women are regarded as an inferior species by most of the patriarchal societies.

Ironically, a woman often carries her baby weighing 10 to 20 kg for a longer period, but, she is stereotypically regarded as unfit for “heavy” work. Again, if the society is considered to have two dimensions, the home, and the world, the home is assigned to be the domain of women and the world is for man.

For instance, in the novel “The home and the world” (Ghare Baire) by Rabindranath Tagore, Bimala loses her home when she comes out in the world. Women are generally assigned the tag of being sacrificing, submissive and hence if a woman expresses her desires, she is considered sinful.

Religion, language, caste, and class have defined women differently and hence their experience, like their histories, are different. But, their subjectivities remain almost the same. Feminist critics and critical schools tend to question these biases along with many others.

Various Stages of Feminism in India

Feminism as a literary discipline is full of claims and counter-claims and it is essentially plural in its stratification, which has constantly been intersected with social, cultural and political histories. It is much more than a movement, a concept or a belief and draws support from revolutionary agendas while attempting to separate itself from them to gain more visibility.

Since the pre-colonial period, women was given the private domain and issues regarding their problem never formed a part of any public agenda as bringing out private matters to the public was considered indecent.

During the 19th century, women’s issues came to light. Policy decisions included concerns for addressing their state of oppression. Laws for the abolition of Sati and widow remarriage came into existence. Women’s education, child marriage and property rights for women formed part of various debates and discussions. Ironically, the brainstorming debates between the modernizers and traditionalists focusing on women never actually involved any women.

Uma Chakrabarty points out that reform movements regarding women’s issues during the 19th century were confined among the upper castes, educated elites, mostly concerning “Bhadra Mahilas”. But, it claimed to represent the whole country.

The beginning of 20th century saw the closure of the women’s question. The “more important” issues of Swadeshi movement, national independence left no time for issues of a lesser important species.

After independence, women’s issues became a private matter of the country. Governmental resolutions, the Nehruvian consensus for progress, modernization ideologies, family norms, reinforced the passivity and subjectivity of women.

The obsession of the elites with technological innovation and the notion of development through the increase of per capita income leading to green revolution diminished the role of rural women in the agriculture.

Even today, the policies for rehabilitation of people displaced because of any modernization project are based on the idea of a man being the bread earner of a family and do not contain any provision for compensating families having women as the head or which do not have any male member.

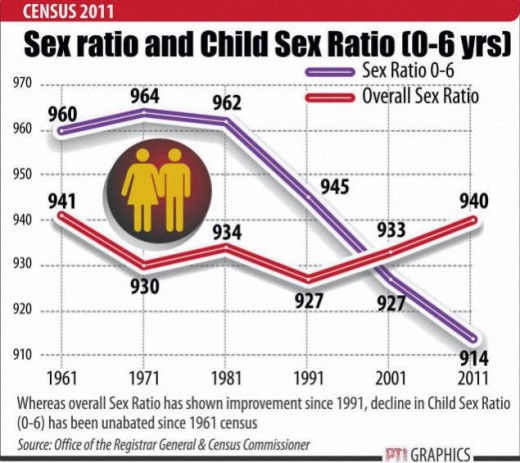

Sad State of Sex Ratio in India

Feminism studies of the 60s and 70s have been a narrative about the reconstruction of female experience and the discovery of representation (Kudchedkar, 2000).

These studies exposed the male bias in the forming of the literary canon where not a single woman writer was given space. Feminists of this period re-evaluated existing texts by women and recovered many lost texts written by women.

Women’s writing is often disregarded for being more emotional in content and passive in action, sometimes they were considered sexually elicit and offensive. For example, Taslima Nasreen’s “Lajja”, which questions the patriarchy embedded in a Muslim society in Bangladesh, is considered controversial and offensive by the society, leading to the issue of Fatwa against her. The work is also looked down by many other male litterateurs.

During the 70s, a key term of intervention, which was central to questions of subjectivity and representation, was “difference”. Three major strategies adopted by feminist theorists during this decade can be broadly stated as follows:

- The first strategy was to consider women as same as men but socially conditioned to behave and think differently.

- The second strategy was to consider women as basically different and it believed that women could advance only if separated from the dominant culture.

- The third strategy argued against focusing on differences. It argued that women are neither merely social victims nor superior, but like men, are to be considered in terms of their individuality (Adele King).

The women’s movements have gained momentum since 1980's. These movements revolve around the question of representation, which is also the key question of contemporary feminism. Feminist theorizing in the post-80s expresses the complexity of resistance and the dangers of conferring a mandatory subalternity to the category of women because women too are associated with acts of oppression against other women.

Feminist theories during the 90s focus on the codes and practices of gender and sexuality. They argue against the patriarchal and heterosexual social norms that dictate ideologies of an absolute difference between men and women. Theories of this period talk about a re-thinking process and focus on the aspects of gender that get deconstructed constantly on the basis of analysis of the Hijra community (eunuchs), homosexuality, etc.

Concluding Note

Critically, the very nature of the feminist questions needs to be interrogated because much of the research is contained within colonial and nationalist paradigms which fail to see that our legal and economic processes are not gender neutral.

Women’s studies should also become non-elitist and involve transactional communication while communicating with people from marginalized communities. Researching from distance with lots of statistics and piles of book and talking about problems of oppressed women may produce a great literary work but the perspective of the problem may vary drastically when perceived from the victim’s point of view.

For instance, a video made by a group of researchers on the problems faced by women in two villages of Maharashtra, on the basis of their observation, was completely different from the video made by the women of those villages. The problems were the same but their perspectives differed completely.

Homogenizing the women’s question is also problematic as the problem of an urban woman can be completely different from those of a rural woman.

Women need to be regarded as individuals and not just as a population known for their sexuality, voicelessness or deprivation because inculcating the feeling of deprivation leads to humility.

Centuries of oppression may not be reversed in a few decades but discussion about their problem at least acknowledges the struggle of 50% of the world’s population for equality.

To conclude, I would like to point out that different strands of feminism have raised more questions than answering them but raising questions is essential in order to answer them.

A Participatory Video Made by Women from a Village in Chhattisgarh

References Used

Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens, Theorizing Feminism by Uma Chakraborty, published by Stree (2003), Calcutta.

Articulating Gender: An Anthology Presented to Professor Shirin Kudchedkar edited by Anjali Bhelande, Mala Pandurang and published by Pencraft International (2000), Delhi.