Population of India: Latest Demographic Trends

Poverty Leads to High Population Growth

India Is Seeing A Rapid Demographic Transition

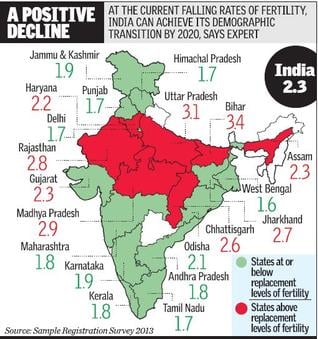

The most recent fertility data published in late 2014 indicates that India is in the midst of a rapid demographic transition. It is expected to reach the replacement level of 2.1 by 2020.

Data from the 2013 Sample Registration Survey (SRS), done by the Registrar General of India, shows that India’s national average Total Fertility Rate (TFR) – the average number of children that will be born to a woman during her lifetime – has fallen to 2.3. It was 2.4 in 2012 and 3.6 in 1991. What is heartening is that fertility is declining rapidly, even among the vast pool of poor and illiterate. The decline is only going to be faster in the coming years.

There is much optimism now that the replacement fertility of 2.1 will be reached by 2020. Accounting for child mortality, the TFR of 2.1 is taken as replacement level fertility when a woman gives birth to average 2 children, of which one will be a girl – the girl replaces her mother. When the TFR goes below 2.1, the population starts to decline.

Fertility rates much below 2.1, such as 1.4 in Japan and Germany or 1.3 in South Korea face unique problem: rising population of elderly and shrinking work force; both put pressure on economic growth. China will soon face such a scenario in perhaps bigger intensity because it forced fertilities to decline in much shorter time frame with its One Child Policy. In India, the decline has been smoother over longer duration, so these issues will not be dramatic.

Wide Regional Diversity in Fertility

Although the general trend of falling birthrates prevails across the country, there are wide regional differences. Of the 29 States, as many as 11 states — West Bengal, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka and Odisha — have already brought down fertility level to 2.1 or below. Lowest fertility state is West Bengal (1.6), followed by Tamil Nadu, Himachal, Delhi and Punjab all with 1.7. The best known State for social development Kerala has TFR 1.8.

These fertility levels match the TFRs of developed countries. West Bengal’s TFR (1.6) roughly equals that of Canada, and Tamil Nadu’s TFR (1.7) equals that of Denmark.

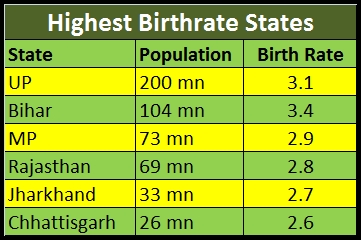

But 9 States still have higher fertility levels – 8 states have TFR either higher or equal to the national average. Naturally these states are propelling current population growth. The most problematic states are Uttar Pradesh and Bihar with TFRs 3.1 and 3.4, respectively. Other laggards are Madhya Pradesh (2.9), Rajasthan (2.8), Jharkhand (2.7) and Chhattisgarh (2.6).

UP and Bihar together form about a quarter of India’s population; and together these six States make up around 500 million or 40% of country’s population. The top 4 are typically called the BIMARU states and they have been developmental laggards for a long time now.

The high-fertility states have TFR levels comparable with those of the poorest African nations. Uttar Pradesh with a TFR of 3.1 is comparable with Namibia and Bihar (TFR 3.4) is comparable with Haiti, Swaziland or Zimbabwe.

Which is the bigger threat to Earth's Well being?

Factors That Affect Fertility

There are 3 known social factors that influence fertility levels:

- Female literacy rate

- Per capita income, and

- urbanization

Female literacy has the greatest bearing on TFR level, followed by per capita income and urbanization. The SRS data show that almost all high-fertility states have low per capita income, lower female literacy levels, or have lower urban population.

However, Gujarat and Odisha are only two major exceptions. They are situated in the Western and Eastern ends of the country. Gujarat is a high per capita income urbanized state with above-average female literacy. Yet, its TFR (2.3) is higher than Odisha’s 2.1. On the other hand, Odisha is counted among the low-income states and has large rural population. Its female literacy rate is also marginally below the national average.

It could be a case of success of State family planning programs in the poor Odisha State. In contrast, being financially well off, Gujaratis are not really very concerned about their family size. But being close to replacement level, it is really not a big issue.

Some Worrying Signals

While the falling fertilities may be easing the population concerns, there are other things that point out that India’s reproductive healthcare system needs further improvement. For example,

1. Maternal mortality: The maternal mortality is still high, although on decline. The SRS 2013 shows it to be 167 per 1,00,000 live births for the period 2011-13, compared with 178 in 2010-12. The fifth MDG target had placed it to be 140 deaths by December 2015. Whether or not India meets the target, further improvement in healthcare facilities is still needed.

2. Under 5 mortality: India has done well in reducing under-5 mortality numbers from 2.5 million in 2001 to 1.5 million in 2011. There has been a consistent decline in Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) and Under-Five Mortality Rate (U5MR) in India. But the progress is appears slower.

For India, the IMR target is 28 per 1,000 live births and the U-5MR target is 42 per 1,000 live births. The current IMR is 40 per 1,000 live births while the U5MR is 49 per 1,000 live births. In IMR, neighbouring Bangladesh (33) and Nepal (32) do better than India.

The IMR has fallen faster in rural areas than in urban areas. Among the big metro cities, Chennai has the lowest IMR (16). And among states, Kerala has the lowest IMR at 12 per 1,000 live births. The nearest best performers are Delhi and Maharashtra, which have IMRs that are twice that of Kerala. Bihar has the country’s highest infant mortality rate of 55 per 1,000 live births.

It must be noted that diarrhoea and pneumonia account for the maximum number of under-5 mortality incidence in the country. In 2010, the under-5 mortality in India from diarrhoea and pneumonia was over 600,000, the highest in the world in terms of absolute numbers.

3. Higher IMR in girls: In the under 5 category, there is higher mortality rates both for infant girls and for girls under the age of five than for boys. This is contrary to the global trend. It must be indicative of gender discrimination – girls being not looked after as well as boys.

Government Focussing on Unmet Contraception Needs

Apart from extra focus on higher fertility districts, the health ministry is also concentrating on meeting the unmet contraception needs. In India, the unmet contraception need is about 21.3 percent as per official data. States like Bihar have 33.5 percent unmet contraception need, Meghalaya has 32.7 percent and Nagaland 33.8 percent.

India plans to spend $2 billion to expand the family planning services to 48 million additional women, apart from sustaining the current coverage of over 100 million users till 2020. In the long run, this helps bring down the MMR and infant mortality rates as well.

Population Projections

The World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision projects India’s population likely to be around 1.62 bn by 2050, when China will have 1.38 bn people. But Deutsche Bank economist Sanjeev Sanyal has a much more optimistic projection. He predicts that in 2050 India will have 1.52 bn people and then the population would reduce to 1.45 bn in 2100. These estimates are about 100 million lower than other such forecasts.

Thus, in the light of these predictions, India is likely to add at best around 300 - 350 million people before its population peaks in the next 4-5 decades.

Sanyal’s prediction for global population is also on the lower side than what the United Nations currently predicts. He predicts that the global population will peak at 8.7 billion in 2055; it will then decline to about 8 billion by 2100 which is lower by 2.8 billion than the UN projection.

Looking at the global trend of falling fertilities, the most extreme Malthusian fears of a ticking population bomb is really without substance.

Conclusion

If India really succeeds in taking care of the unmet contraception need, particularly in the states like Bihar, it should the target of 2.1 TFR by 2020. It means India’s population should peak in around 2050 in the range 1.5 – 1.6 billion. The ticking population bomb type of worry of the 1970s has really no basis today.

However, poverty will still remain a challenge so will be the task of employing the massive young pool of citizens. The weak status of women is still a widespread social problem, which is at the core higher fertilities. So the family planning battle must firmly anchor on the social plain now.