Being a Latter-day Saint (often called "Mormon") and Black in America: Beyond the 70% Stat of Father Absenteeism

Episode Ten

What if the Worst Claim about Fathers Who Are Black Is Built on Selected Data?

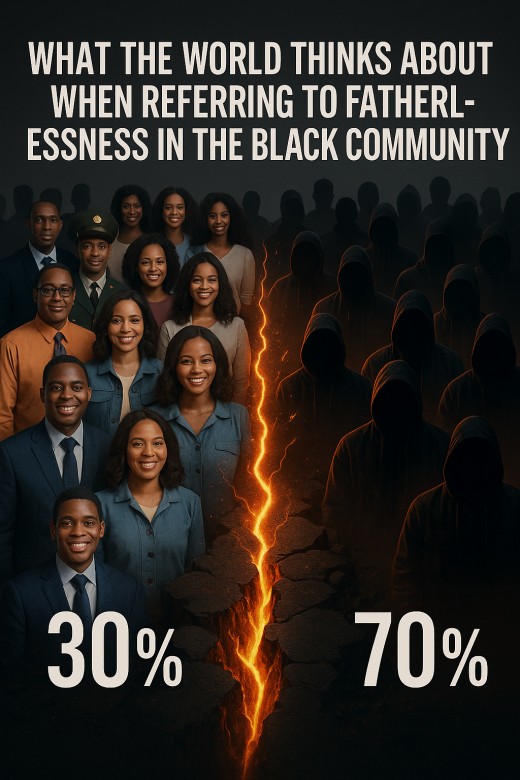

Statistics are not proof of anything except that people know how to twist them to justify a stance. Sixty-eight to seventy-two percent of children who are Black in America are born to single mothers. That is a painful, loaded figure when viewed narrowly: a number that invites judgment. From it, some conclude that we are broken, that fathers vanish, that those who are Black are “others” — different, less, apart.

But let me show you what that statistic doesn't—and cannot—reveal:

-

Fathers of those children are still often deeply involved in their lives.

-

Many couples of Black heritage may not legally marry, but live as though married.

-

Fathers who are Black attend school events, sports games, and parent nights.

On the surface, it looks like abandonment. Some of it is true. But to assert that 70 % of people who are Black have no father in the home is misleading, because many fathers remain active, connected, fighting in ways unseen. That statement becomes a weapon—used to brand a people unfairly.

And now, let me pivot to something delicate: I share some of Charlie Kirk’s goals—strengthening family, urging responsibility, uplifting faith. But before we hear his quote, understand how it is received. Many have labeled him a racist for statements he’s made about Black communities, especially when he said, “We have a lack of father problem in the Black community, especially in Chicago.” [1] Critics often treat statements like that as verdicts, leaving out nuance, context, and the fact that words reach different audiences. Still, parts of what he says deserve engagement—if we listen carefully, not dismiss reflexively.

He also urges: “Get married and have children.” That’s a worthy call. But applying it fairly demands humility, understanding, and recognition of complex lives—not simple judgments.

I don’t care what you look like, I care what your worldview is. The Left have become the true racists. They say — Mexicans cannot be conservatives — they say Black people cannot be conservatives. That’s a racist thing to say.

— Charlie Kirk Turning Point USA Youth Latino Leadership Summit, 2022

Here’s My Story: Presence Across Distance

I still feel that moment. I was fifteen, riding with my mother and my brother on the highway from Georgia to New York to see my newborn nephew. It was the first time I would see my father since I was three. My heart raced. I was terrified he might deny me. Inside, I carried a hollow ache — seeing cousins with dads, hearing the word “Dad” used freely in rooms where I felt silent.

When I looked at him, I studied his hands, his posture, his voice, and recognized pieces of myself. He claimed me. He told me he loved me. He insisted I respect my mother. He warned me never to dishonor her. He didn’t live in my home while I was growing up, but he reached for me.

Later, he asked if I would live with him. I refused — not because I didn’t want him, but because of loyalty to my mother and the ties that held me. Still, that offer meant something. Another time, when I planned to leave the country as a missionary, he forbade it, haunted by his own past abroad. I didn’t obey. But knowing he cared enough to warn me showed me he fought for me. That’s fatherhood.

There was presence even in absence. I learned to show up partly from what my father could not always show — not out of failing but circumstance — and partly from my stepfathers. My first stepfather made mistakes, including cheating, and that hurt us all. But my second stepfather, the one who stayed true, demonstrated kindness, loyalty, and consistency. He still calls me “son” today, though he and Mother separated and he remarried. Their combined influence taught me about steady love, even when life’s edges were jagged.

Would it have been easier had he lived in my home? Yes. But from those fragments he offered, I became who I am. I raised my children in my home. Through absence and presence both, I learned how to show up — and why it matters.

So, when crime data is used to condemn, I say: Yes—examine the laws, the courts, the resources, and the neighborhood conditions. But never let a statistic define someone’s dignity.

Crime, Conflict & Complexity

I won’t pretend crime doesn’t affect communities where people who are Black live. It is a harsh reality. But crime is not a moral verdict on a race—and it does not erase fatherhood.

Yes, some succumb to destructive paths, influenced by environment, lack, or exposure. But that doesn’t cancel out the efforts of fathers. Children may be pulled into harmful cultural patterns—even while their fathers strive in other ways.

Sometimes mothers restrict access for reasons of fear, trauma, or protection. Some courts cost too much, require powerful lawyers, favor those with means. My mother moved me thousands of miles from my father when I was three. She never maligned him—she spoke of his virtues. Later I learned she left because of instability, unfaithfulness. Her choice cost me access. The breach was real.

Here’s what the data show—without moralizing:

-

In 2019, people who are Black made up ~ 26.1 % of adult arrests even though their share of the population is smaller.

-

Many jurisdictions incarcerate people who are Black at more than three times the rate of White individuals.

-

In local jail admission data, Black persons are admitted at over four times the rate of White individuals and often stay longer.

These figures reflect how the justice system functions, how policing, courts, representation operate—not guilt by birth. They show how many are drawn into legal mechanisms. But they do not erase fathers trying, children who love.

We must reject two extremes:

-

Denial: pretending crime doesn’t exist

-

Universal condemnation: branding an entire race as defective

The genuine story holds tension: fathers may try, fail, fight, grieve—and still persist. Children inherit both promise and wound. Some wounds are personal. Some come from law, access, and resources. Love endures.

So, when crime data is used to condemn, I say: Yes—examine the laws, the courts, the resources, and the neighborhood conditions. But never let a statistic define someone’s dignity.

I won’t pretend crime doesn’t affect communities where people who are Black live. It is a harsh reality. But crime is not a moral verdict on a race—and it does not erase fatherhood.

Light Evidence That Supports, Not Overwhelms

When fathers are asked in national surveys about caregiving—feeding, bathing, playing—some nonresident fathers report doing exactly those things. In the Fathers’ Involvement With Their Children (2006–2010) report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 30 % of nonresident fathers say they bathed or played with their children in a recent month. [6]

In studies that follow people over years, young people of different races often report comparable closeness to their fathers once factors like income, living situation, and schooling are accounted for. [7]

In interviews with fathers who are Black, many speak of quiet gestures—late phone calls, surprise visits, errands, being quietly present in small ways. These are acts that statistics rarely capture, but the heart never forgets. [8]

And there’s this fatigue: what’s often called “Black fatigue.” It’s not weariness in the way others use it—but the exhaustion of having the worst parts of a few used to define us all. The burden of having to prove your presence, to push back stereotypes, to carry dignity under numbers that misrepresent. This misapplied narrative wears people out.

I have a friend right now doing everything he can—even when it seems like the cards are stacked against him. He loves his children. But the mother relocated them to another city. He has no reliable vehicle. He can’t just show up. He waits on her goodwill. He feels the weight: “Maybe I’ll lose them.” That despair is not weakness—it’s a response to pressure. Yet he hasn’t fully given up.

We also know that when fathers are present, children tend to be more stable in behavior, academics, and emotional health, whether under a single-father home or a two-parent home. Father's presence adds a foundation, even when life is not perfect.

This evidence does not erase our story. It echoes it. It lends a counter-voice to how people have lived: their faith, fear, love, and resilience.

What I Believe:

“Never let a problem to be solved become more important than a person to be loved.”

— President Thomas S. Monson, Finding Joy in the Journey, October 2008 [9]

Above all, the Atonement of Jesus Christ is my anchor. It is the enabling power by which any of us can overcome trauma, move past the weight of the past, and walk forward in faith, hope, and love. Because of Christ, I believe wounds need not define identity; loss need not decree hopelessness.

I have witnessed my life change by His grace, and I have seen that change in others. When people accept Him and seek to be His disciples, they find room to forgive trespasses done against them, to let bitterness go, to open toward peace instead of sinking into victimhood. The past remains, but it does not have to own us.

As a man who is Black in America, I do not pretend that trauma, prejudice, or hurt aren’t real. But I testify that the Savior’s power is greater. He heals the shattered soul, gives strength to bear burdens, and offers new beginnings. We can refuse to allow a past injustice to weigh more than a person’s possibilities.

My testimony is simple: I have experienced His grace. It has given me the courage to move forward, to try again, to love despite pain. Because of Him, I believe we can be transformed—not by statistics, not by labels, but by a love that redeems.

I will not allow numbers, crime narratives, or popular assumptions to weigh heavier than a life.

Presence is lived—not boxed in census lines or legal definitions.

Fathers who are Black do try. They persist. They love—even amid failure, hardship, distance.

I reject narratives that flatten humanity or deny dignity. My story carries scars and light. It is more than a percentage.

References

-

Statistics Don’t Lie: Black Fathers Are More Involved in Their Children’s Lives. (2024). NJ Urban News. — Black fathers more likely to engage in daily caregiving tasks than White or Hispanic counterparts. Retrieved from https://njurbannews.com/2024/07/02/statistics-dont-lie-black-dads-are-more-involved-in-their-childrens-lives/

-

Race/Ethnic Differences in Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement After a Nonmarital Birth. PMC / NCBI. — Black nonresident fathers were more likely than Hispanic fathers to spend time and engage with children. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6133319/

-

Jail Inmates in 2019. Bureau of Justice Statistics. — Local jail incarceration rates: Black ~ 600 per 100,000 vs White ~ 184 per 100,000. Retrieved from https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji19.pdf

-

Racial Disparities Persist in Many U.S. Jails. Pew Trusts. — Black people admitted to jails at rates 2–6× higher than White people, with longer stays. Retrieved from https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2023/05/racial-disparities-persist-in-many-us-jails/

-

Prisoners in 2019 (Mass Incarceration Trends). Bureau of Justice Statistics. — Black Americans represent ~ 33% of prison population while ~ 14% of U.S. population. Retrieved from https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf

-

Fathers’ Involvement With Their Children: United States, 2006–2010. (2013). National Center for Health Statistics. — Report on father involvement whether co-resident or nonresident. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr071.pdf

-

American Dads Are More Involved Than Ever (2023, October). Institute for Family Studies. — Report on time use and father involvement across demographics. Retrieved from https://ifstudies.org/ifs-admin/resources/briefs/ifs-wang-fatherstimebrief-oct2023-1.pdf

-

Understanding Key Barriers to Fathers’ Involvement in Their Children’s Lives. (n.d.). Duke University / Nursing Department. — Discusses systemic and practical barriers to father involvement. Retrieved from file (or institutional URL)

-

Monson, T. S. (2008, October). Finding Joy in the Journey. General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved from https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2008/10/finding-joy-in-the-journey?lang=eng

Related

- Being a Latter-day Saint (often called "Mormon") and Black in America: Foundations of Faith and Iden

The leadership gets it. The rest of us Latter-day Saints still need to work on it. Volumes of books could be written on what it's like to be a Latter-day Saint as a Black American. God desires us to overcome our crosses, our own or an institution's. - Being a Latter-day Saint (Often Called “Mormon”) and Black in America: Black Is Skin Deep — Episode

All humans belong to God and He wants all of humanity to be with Him. “God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life,” John 3:16.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Rodric Anthony Johnson