Gender in Islam: Gendered Control Through Beliefs of Powerful Women

Why are women viewed as ‘powerful and dangerous beings’ and how does the ‘system’ protect itself from this danger and power?

‘In Western culture, sexual inequality is based on belief in women’s biological inferiority… In Islam there is no such belief…on the contrary; the whole system is based on the assumption that women are powerful and dangerous beings’ (Mernissi, F. 1971. Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in Muslim Society. p.19).

Islamic belief understands women to be powerful and this power must be constrained. This is the foundation of segregation between men and women, and the prevention of women’s access beyond domestic life. Forcing women into this inferior status, with little or no access to roles of superiority, is thought to deny them access to these sources of power. Contradictorily, women are also seen as weak as they lack an independence from nature which has control over menstruation. Although Islam affirms the potential for women and men to be equal under Umma, this seems to fails in all respects to cross over into reality. However, any sexism cannot be put down to being purely the result of religion but also the result of social customs, if not more so.

Purdah, literally meaning ‘screening’, is the primary source of sexual segregation in Muslim societies. Segregation is based on ideas of modesty and honour practiced throughout the world with variations in strictness. The Purdah system ‘limit’s a woman’s mobility outside her home…[and is an] example of highly segregated systems of sex role allocation’ (Papanek, H. 1971; 517). Enforcing the purdah contradicts the Islamic view which stresses ‘equality of all believers before God…[as it] clearly puts men a step above women’ (Papanek, H. 1971; 518). Qualities of honour and modesty within social structure are susceptible to both sexes. However, it is socially considered that women have greater responsibility as they are more susceptible to failure in maintaining these qualities and ‘male honour is dependent upon the unsullied honour of women’ (Pastner, C. 1974; 409).

Purdah is considered a protecting force rather than an attempt to constrain women’s freedom. In ‘limiting physical and educational mobility of women, retaining them within social network which excludes non-kin male and imposing certain standards of dress’ (Pastner, C. 1974; 410) the purdah acts to constrain women and their power while protecting men from the distraction women present from devotion to Allah. Though it cannot be said that women have no control within their society, or at least their role within it. Women can manipulate the system slightly to get their own way. Methods within the household include ‘withdrawal of sexual favours, refusal to perform domestic duties, excessive complaining and uncooperative behaviour towards other women in the household’ (Pastner, C. 1974; 411). However, methods of gaining influence rely on ‘male awareness of their dependence on women for the successful maintenance of the domestic arena of society’(Pastner, C. 1974; 411). So women’s freedom does rely on appreciation of the importance of their role as members of the household. It is not fair to assume restrictions only apply to women; although women’s restrictions are much greater than men’s. Men are ‘more constrained by rules of overt conduct because most male interaction takes place in public social arenas’ (Pastner, C. 1974; 412). So it seems women have more means of undermining the system within their domain while in the public sphere men must always adhere to the strict code. Nevertheless, it is women who must bear the pressure of having such limited freedom and having to follow such strict rules at all times due to the greater power they are perceived of having.

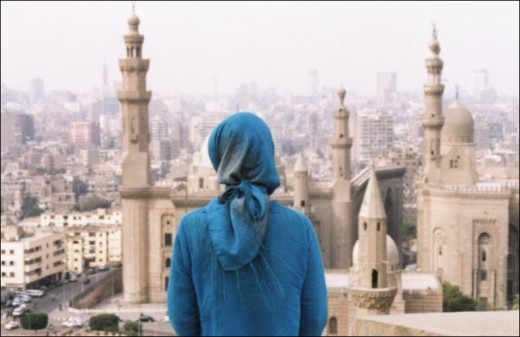

Within the system of containing women’s power exists codes of dress which vary greatly in rigorousness depending on location, society, and the preference of individuals and their kin. ‘Throughout the Arab world, women’s rights in general, and the wearing of the veil in particular, are subject to wildly differing perceptions’ (Burgat, F. 2003;140). Sometimes veiling is perceived as protection from men while it is also thought of as a method of subjugation and segregation; acting only to limit the freedom of women in society. The veils many diverse and symbolic meanings can be construed as both a form of protection and of subjugation, of allowing freedom and of withholding freedom; it differs depending on perceptions. The most positive of the features of the veil seem to be that it offers ‘protection that everyday clothing can no longer guarantee’ (Burgat, F. 2003; 431) within a society in which the integration of the sexes is not well received. Veiling is particularly relevant in the ‘achievement of social distance: veils are often seen as devices which increase the sense of mystery and remoteness of the wearer’ (Papanek, H. 1997; 520). This ‘remoteness’ resulting from wearing a veil though seems to serve ‘only to enhance those qualities which are already there, as socially defined-attractiveness and vulnerability among women’ (Papanek, H 1971; 520). The social structure thus seems to constrain women’s power, not only in the hierarchy, but also in their physical appearance. The veil is mainly worn in front of those above the woman in the social hierarchy, so can also be a means of bowing to authority of, chiefly, the men above her status; a means of suppression.

The social structure of Mafia Island seems to treat women fairly equally compared to other areas founded on Islamic fundamentals. To begin, a cognatic descent system is used allowing every individual to belong to a kin group as even a child not born to a woman’s husband still belongs to a decent kin; women’s lines of kin are of equal importance in a child life as men’s. Compared to many other societies, women in Mafia Island have ‘a fair degree of autonomy’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 23). Women can look after themselves though tend to be better off married. Although customs tend to support a ‘complex cognatic descent groups, communal property-holding, egalitarian social relations’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 24-25) which are relatively equal for men and women; there also exists ‘notions of private property, of social stratification based on ethnic affiliation…and on the superiority of men to women’ (Caplan, P.1984; 25). Thus it seems the foundations of the social structure rely on a contradiction of sorts.

The reality that women are less free than men in Mafia Island is most evident in property rules. Trees are inherited in Mafia according to Islamic law which bestows women with ‘half of a mans share, and she can never be the sole heir’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 28). Although this is obviously a disadvantage for women, it is also true that women get to inherit trees entitled to them with ‘no attempt made (as in other Islamic countries) to prevent women from getting their rightful shares’(Caplan, P. 1984; 28). Divorce rules for property also give women rights over property as ‘trees are evenly divided if the couple worked together on the cultivation’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 28). Although property rules seem to be in many degrees equal, women rarely own as much as men as ‘on average, adult males own 125 trees pre head, while adult females own only 36’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 28). However, this does gain a sense of balance as ‘men are responsible for maintaining their wives and children…whereas women are free to spend their cash as they please’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 28).

All of these unequal property rules have groundings in the ideas of men being responsible for their family’s welfare, and of women being placed in the role of wife and mother, rather than that of owner and cultivator. A distinct division of labour seems to exist which relies on women accepting their role as below men in the hierarchical structure. Women tend to own every sort of property less frequently then men as men own more cattle, donkeys and boats. Donkeys are very rarely owned by women, not only due to cost but, because they are used for ‘carrying goods for other people… an occupation in which women never engage’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 29). Boats are never owned by women, again due to cash but also because ‘women in this area neither fish nor handle boats’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 29). Freedoms of women are restricted as, although theoretically possible for them to possess certain things, they lack the practical uses which men would wield them for as women do not, or are prevented from, engaging in these activities. This also means ‘men have more ways of making cash and investing in capital than do women’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 29). These things women are prevented from participating in means they cannot earn the money they are, in theory, perfectly entitled to earning and having.

Women’s means of earning money is limited as ‘virtually their sole means of earning money is by making the plaited grass mats for which the island is famous’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 29). Men though also have restrictions placed upon them. In their role as husband, a man is duty bound to ‘support his wife by providing her with a house, food and clothes’; according to Islam ‘it is very clear that it is a husband’s support of his wife that gives him authority’ (Caplan, P. 1984, 32). This relationship is reciprocal as ‘women do have rights in their husbands [however] these are usually limited’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 32) especially in relation to the rights a husband has in his wife. In the case of possessing cash women have much greater claims to their husbands wealth than a man would to his wife’s; ‘a man can only ‘borrow’ from his wife and must repay her’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 33). Women have full claims and rights over her own property while men are obliged to share their wealth with their wives and families to support them. So it seems that, although ‘both men and women hold membership in their own right, and so both have access to land’ (Caplan, P. 1984; 25), it is men who have more access and ability to earn money in order to invest and gain. Women are much more limited in their capability despite the apparent equality of the sexes.

Control of women within Pakistani society extends to marriage and a woman’s ‘freedom’ to marry who she wants. This is controlled mostly through the zina ordinance which acts to regulate what ‘constitutes ethical behaviour in sex, and, more generally, within the family and the social institution of marriage in ways in which women’s fundamental rights under the constitutions, and some argue in Islam, are violated’ (Khan, S. 2003; 76). Women, in theory, are free to marry whomever they want, but under zina her family can often act to secure the woman’s punishment under law for disobeying her family’s wishes; ‘zina laws allow the state to identify and regulate sexual conduct as a crucial element of creating a just society’ (Khan, S. 2003; 78). Zina laws are used to intimidate women into obedience with the ‘threat of imprisonment for those daughters who have married without [family‘s] permission suggests parental right overrides men’s right/claim to their wives’ (Khan, S. 2004; 84). There have been cases in which women have claimed that, although married, her family claims she was not so it appears she was committing adultery. One case found a woman claiming ‘her parents had bribed the officials who performed and registered the marriage to say that no marriage exists’ (Khan, S. 2004; 84). Khan’s findings suggest that most women imprisoned under zina ‘are not there because of sex crimes but because their families or former husbands used the zina laws to jail the women when they went against their families wishes’ (2003; 77). The freedom which theoretically exists in women’s marriage choices seems not to relate into reality. Pakistani laws do not allow families to force an adult-woman into marriage without her consent but ‘this does not always translate into legal practice for Pakistani courts have given contradictory rulings on this matter’ (Kahn, S. 2003; 80). Zina laws also tend to target weaker members of society; effectively weeping ‘the streets clean of women, particularly poor unwanted and rebellious women’ (Kahn, S. 2004; 87). These women are usually illiterate and have no money to afford bail. If from a wealthy family then ‘bail has to be posted by a male: their father, their brother or their husband’ (Kahn, S. 2004; 87). These male relatives are often responsible for the women’s being in prison in the first place. It also seems that wealthy families have enough influence to ‘keep their daughters out of prison and thus within the reach of their vengeance’ (Khan, S. 2003; 81).

Due to the payment of ‘bride-price…women become property to be bought and sold’ (Khan, S. 2004; 83). Women who resist this convention are those liable to being accused of zina. Although zina laws are religious, women claim their religion allows them freedom to choose who to marry, it is the law preventing this freedom; as Saima, convicted of zina, claimed ‘‘My religion allows me to marry who I want’’(Khan, S. 2004; 84). It must also be acknowledge that men suffer as a result of zina laws; young men can be equally powerless in deciding their destiny and can end up imprisoned. The application of zina laws creates ‘docile daughters, mothers and wives’ (Khan, S. 2004; 86). Critics of zina laws argue it ‘contributes to the growing incidence of state-sanctioned violence against women’ (Khan, S. 2003; 77). In her study, Khan was unable to contact any women who had been released from prison after accusations of zina, it was thought this was because women who returned to their family were kept within the family’s control, while those who did not return home had to disappear and begin life again, anew.

In conclusion, it seems the social structures throughout Islamic states attempt to place state sanctions and methods of control upon women. Women’s freedom, not only to work and practice certain things, but even to roam is greatly limited. These sanctions of control are explained as methods of domination of women’s powers and as means of conforming them to the social roles they need to fill to maintain a functioning society. This though, unfortunately, resulted in the profound restraints on women which still exist under the guise of religious regulations.

Bibliography

Burgat, F. 2003. Face to Fact With Political Islam, I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd, London.

Caplan, P. 1984. “Cognatic Descent, Islamic Law and Women’s Property on the East African Coast”. Women as Property. (eds.) Renee Hirschon. Croom Helm, London. 23- 43.

Khan, S. 2003. “Zina” and the Moral Regulation of Pakistani Women. Feminist Review. 75 (1): 75-100.

Khan, S. 2004. Locating the Feminist Voice: The Debate on the Zina Ordinance. Feminist Studies. 20 (3); 660-685.

Papanek, H. 1971. Purdah in Pakistan: Seclusion and Modern Occupations for Women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 33 (3): 517-530

Pastner, C. 1974. Accommodations to Purdah: The Female Perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 36 (2): 408-414.