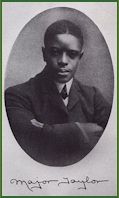

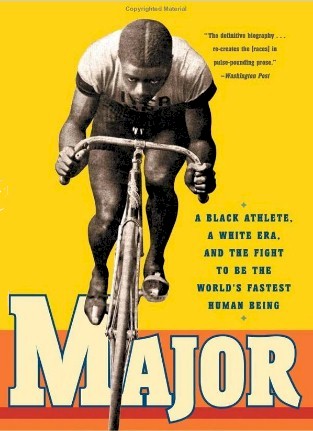

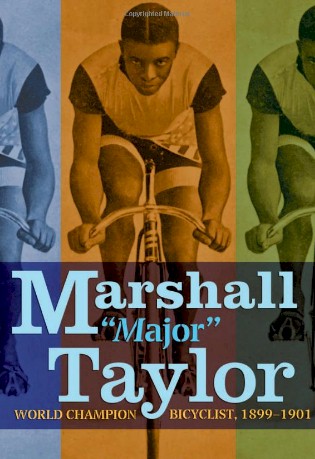

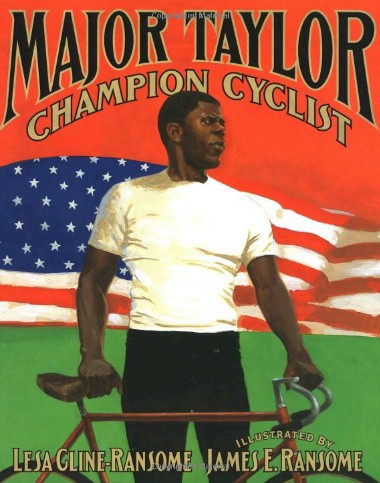

Major Taylor-A World Champion 1878-1932

The Most Popular Sport

At the turn of the 20th century, cycling was the most popular sport. Bicycle racers were the stars. This was still the period of reconstruction of the south. Often blacks were treated as bad as and worse than the period of slavery. It was this period that Major Taylor, a black athlete became the highest paid athlete and the fastest man in the world.

From the mid-1890s to the early 1900s bicycle racing was the rage. Bicycle racers were heroes and raced in dozens of major cities across America. Their images grace packages of cigarettes.

In 1899 when Major Taylor began his assault on cycling’s record books, 400 blacks were lynched in Georgia, Mississippi, and a half dozen other states. It wasn’t the safest time to be a victorious and prominent black man.

Gilbert and Saphronia Taylor had left Kentucky with their three small children and crossed the Ohio River into Indiana in the early 1870s. The promise of prosperity along the railroad and canal route, where they had settled to farm a small plot of land, did not come to pass. Gilbert took a job as a coachman with a rich white railroad family. His dream of being his own boss had died. Gilbert was a veteran of the Union Army and the Civil War. Records of marriage and other statistics were not kept with a lot of blacks. The 1870 census stated that the Taylors couldn’t read. The history of Gilbert and Saphronia may have been obscured from shame of slavery.

Marshall Walter Taylor was born to Gilbert and Saphronia Taylor on November 26, 1878. Marshall’s older siblings were Lizzie, Alice, and William. Very soon three more children would join the four. Marshall would assume responsibility for the younger children. Years later his records would show gifts of shoes to his lamed brother John and his younger sisters Eva and Gertie.

As a young boy with a lot on his shoulders, his mother would instill the rules of Christendom. Life would be a contest of stamina in a race against sin. Punishment in the hereafter would be applied equally to white and black sinners. There was no qualifier, no fuzzy score keeping, and no gray line.

His mother’s influence grew stronger through every stage of Marshall’s development. As he aged he sought his mother’s advice more and drew the family around him has they had been around her. In his prime at least three of his family would live with him. He saw to the entire family.

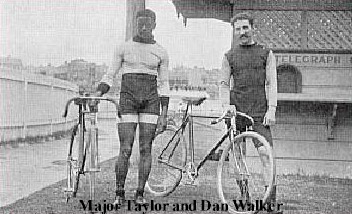

A childhood friend of Marshall’s would be Dan Southard. Dan was white and the son of a wealthy businessman. Dan would move away with his parents and Marshall would be prevented to go with Dan by Marshall’s mom. Before their parting Dan would come into the possession of two bicycles. Both would ride well but Taylor taught himself to ride backward, balance on his wheel’s spokes, and pedal with his hands.

With Dan Southard and other rich white boys, Taylor rode the fastest. Perhaps unable to eloquently describe as a ten-year-old, he knew that the bicycle bequeathed the one thing that America promised but didn’t deliver—freedom.

When Saphronia told her eleven-year-old son that he could not go to Chicago with the Southards, Taylor went from “the happy life of a millionaire kid to that of a common errand boy, all within weeks.” Even with the persuasive support of the Southards he had been refused membership to the YMCA. Now he would see more ignorance, racial hatred, poverty, and prejudice. In Jim Crow Indianapolis he could take the trolley but his seats would be of those last three.

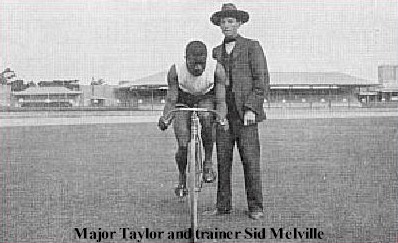

Taylor became a reliable paper boy. In 1891 Tom Hay of Hay and Willits gave Taylor a $35 bike and $6 a week to ‘sweep and dust” and perform his “homemade tricks” in front of their bike shop. Taylor wore an officer’s uniform and Hay billed him as the “major.”

Months later Hay and Willits sponsored a 10 mile handicapped race for the cream of amateur riders in Indianapolis. The event started near the shop and when Hay saw Taylor near the start, he invited the thirteen-year-old boy to jump in and offered Taylor a fifteen minute head start. Taylor refused but Hay insisted. It was now a hare and hound format with a black boy being chased by a white mob. As the band played and the crowd cheered, Taylor cried. When Hay saw Taylor he started to lift him from the bike. Instead he whispered, “I know you can’t go the full distance but just ride up the road a little way, it will please the crowd, and you can come back as soon as you get tired.”

Around this time the “perfect cyclist” was described: “The style of man to be chosen for bicycling should be one above medium height, with wide hips, long legs and powerful thighs, with a chest big enough to give full play to the heart and lungs.” The teenaged Taylor weighed less than 100 pounds and had twigs for legs.

The pistol exploded and the chase began. At the halfway mark he ached and wanted to quit. Taylor would have been a ghost participant had he not finished. He was placed in the race at the beginning by chance. Like his father in the Civil War, he was there but not. For reasons he could not comprehend, “he rode like mad.” In the last few hundred yards he could hear Walter Marmon who fit the description of “perfect cyclist” bearing down on him. Taylor crossed the finish line with less than three lengths to spare. Taylor avoided the humiliating capture. He was awarded the gold medal for the race. As fast as he had ridden in the race, he rode even faster home to show his mother that medal.

Gilbert Taylor was apprehensive of his son’s gift. Gilbert was the coachman and day laborer who spent much of his life avoiding confrontations with whites Now his son was doing the opposite. God help him.

Taylor won many amateur races and established himself with Indianapolis’ cycling elite. Birdie Munger, a bicycle builder, took Taylor under his wing.

In 1894, the teenager had a plan. He persuaded Munger to lend him a bike and go out to the track as Walter Sanger, a six foot three 200 pound Chicagoan was attempting to set the mile record. Moments after the veteran completed his victory lap for setting this new record the Major made his move. Taylor sneaked in with his borrowed bike and began whirling around the 2 tenths mile oval track with clear intent. The record was documented with pacers, timers and other means from the various clubs. Taylor easily surpassed the record just set minutes ago by Sanger. Shortly after Taylor was banned from the Indy tracks. Taylor broke two world records- for the 1 mile ride both paced and un-paced.

Taylor sneaked into the seventy-five-mile Indianapolis-to-Mathews road race. Just after the starters pistol Taylor jumped from his hiding place and chased down the pack of riders. He caught and passed and won by a good margin. This established him as the foremost racer in the state. He didn’t tell his mother about this race as it was on Sunday and she would have forbidden it.

Because of his notoriety Taylor was not allowed to race many races in the area that he could have easily won.

Bertie Munger stuck with Taylor. Munger was forced from a job because he had teamed with a black racer. In the summer of 1895 Munger and Taylor shook the dust from their feet and moved to Worcester, Massachusetts.

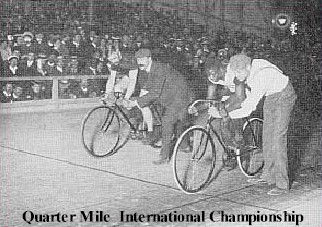

In New York of 1896, the shock would not be that a black boy would get to start the biggest race of the year but what the kid, soon dubbed as the “colored cyclone”, would do in that race.

December 10 twenty eight cyclists dressed in velvety robes and colors of their countries would emerge like gladiators. They would have their own smiling, fist pumping entourages. There was the Irishman, Terry Hale. The crowd of 5,000 stood on their feet as Brooklyn’s Charles Murphy dazzled them with a racing suit of stars and stripes. The roar continued for Frank Waller, the “Flying Dutchman”. It continued for other well-known dignitaries of cycling racing.

Eighteen-year-old Marshall Taylor and his white trainer Bertie Munser entered apprehensively. The crowd reacted as promoters assumed they would. There was nudging and whispering, no doubt snickering at the prospect of a black racer competing in a highly sanctioned race against an all white competition. Taylor was clearly a boy. He was five-foot-six and 130 pounds. He had an anxious look of uncertainty as he looked straight ahead. This was his first professional race.

This was also the Six Day race. This was not about athleticism but the endurance of pain. Sprinters such as Taylor were often the first to be destroyed. A doctor once said the Six Day races took ten years off a man’s life. Taylor was a full ten years younger than the seasoned favorites. Taylor had never ridden a race over seventy-five miles.

After day one Taylor was vying for first. He needed more sleep than the other riders- one hour for every eight on the bike.

Taylor kept pace for two days. After day three he quarreled with Munser about the need for sleep. He rode the next eighteen hours without pause. After seventy two hours he was in ninth place, just 100 back, behind the leader Hale.

After the fourth day his mind wandered. He devoured two fried chickens and four and a half pounds of meat. Several cyclists dropped out and those that remained hallucinated and were the living dead.

The crowds that had been waning were now returning. On day six, he hallucinated, stumbled away, and fell next to the low rail. Before he hit the ground he was asleep. Thousands screamed for him to wake. Stadium personnel ran to help him. When he got back on his bike he unaccountably “raced like a streak.” He finished eighth. The word circulated onto Twenty-Sixth Street. There was absolute pandemonium. The papers trumpeted that Major Taylor was the “wonder of the race”.

In 1898 Major Taylor held seven world records. One was the 1 mile paced standing start- 1:41.4

On August 10, 1899 Major Taylor won the world 1 mile championship in Montreal, Canada, besting Tom Butler. Taylor is now the second black world champion after bantamweight boxer George Dixon’s title fights in 1890 and 1891.

On November 15, 1899 Major Taylor cut the 1 mile record down to 1:19.

September 1900. after being thwarted for years by racism, the Major competes and wins the national champion series and becomes American Sprint Champion.

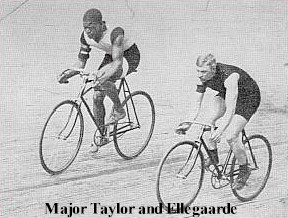

March through June of 1901 Major Taylor competes in Europe and beats every European champion. Because of religious beliefs he resisted had racing on Sundays for years.

From 1902 to 1904 Major Taylor raced all over Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

In 1907 Major Taylor made a brief comeback after taking two years off.

In 1910 Major Taylor retires from racing at 32 years of age.

For the next twenty years his fortune is sapped by failed health and business ventures.

Many racers used dirty tactics such as elbowing or “boxing Taylor in.” Here they would surround Taylor while other riders got away. Taylor was threatened. In many races Taylor bobbed his head from side to side in apprehension of being taken out.

On a drizzly day, on a slick track, a crowd of 25,000 watched as Taylor took second behind Tom Cooper, and Philadelphian W.E. Becker took third. Then the attention was turned to a fracas on the infield. Becker had come from behind and ripped Taylor from his bicycle. Becker’s knee was in Taylor’s chest and Becker was strangling Taylor. By the time the police had dragged Becker off Taylor was unconscious. Taylor remained unconscious for fifteen minutes or more until Munger applied an ammonia soaked rag to his nose. Taylor would write later in his autobiography that he learned that prejudice was not limited to the South.

Marshall Taylor set world records. Taylor was world champion. He would also beat his ruthless nemesis Floyd McFarland who was not averse to dirty tactics in or out of a race.

Major Taylor beat the best racers on all continents.

Taylor was reported to have earned between $25,000 and $30,000 a week when he returned to Worcester at the end of his career. By the time of his death he had lost everything to bad investments (including self-publishing his autobiography), persistent illness, and the stock market crash. His marriage failed. He died at age 53 on June 21, 1932, a pauper in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood, in the charity ward of Cook County Hospital. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Taylor was smart and attentive. He had common sense. He had no vices. He was coachable and hung on Bertie Munger’s every word.

He believed that being the best racer came from being the best person he could be.

Major Taylor-Positively Black

Major Taylor Association

- The Major Taylor Association, Inc.

Our mission: Memorialize Major Taylor with a statue on public land in Worcester, Massachusetts, in recognition of his athletic achievements and strength of character.

Major Taylor

Bicycle How Do I Love Thee?

- Bicycle, How Do I Love Thee?

Ive always loved the bicycle it seems. I dont know when I haven't. How could one not? But, to see it, cycling, done correctly, to see its true proficiency and efficiency being...

Dressing For Cycling In Cold Weather

- Dressing For Cycling In Cold Weather

Dressing to Cycle In Cold Weather There are ways to dress for the cold for maximum comfort and warmth. You can be warm, feel good, and look good. Dont make a fashion faux pas that could result in...

Cycling What Can I Say?

- Cycling-What Can I Say?

What can I say, in a positive way? How can I sway you to come out and play, On a lean, clean machine in a beautiful scene? Who of you will dare to put wind in your hair, Rain in your face and leave never...

Bicycle Pace Line Etiquette

- Bicycle Pace-line Etiquette

Major Taylor Club climbing toward the "Wall" near Townsend, TN. Buckeyes and New Yorkers ride River Road near Burnsville, NC Brothers and sisters from Asheville, NC head toward the Blue Ridge Parkway and the...

Beginning Competitive Cycling-KeysToTheKingdom

- Beginning Competitive Cycling- Keys To The Kingdom

The absolute best thing to do starting out is to take an audit of your physical condition. You should have a physical exam to determine if there are any hidden health issues as you increase the intensity...

Yearly Cycling Training Regimen

- Yearly Cycling Training Regimen

Training is an ugly word to me, especially at my age. In some manner I am indeed training or making an effort to maintain my fitness. There are no off seasons. This isn't a month that is kind to...