Visiting Duesseldorf, Germany and its central railroad station: secrets revealed in changing architectural styles

For your visit, this item may be of interest

Where the 'new' is getting old, and the 'old' style was too new to preserve

As is very widely appreciated, the face of many German, and other European, cities changed greatly in the course of the mid-20th century, not least on account of the immense changes brought about by World War Two, war damage and subsequent urban planning.

I visited Duesseldorf, and had these latent assumptions in mind. Duesseldorf, capital of Nordrhein-Westfalen, suffered particularly heavy war damage, and the mid-20th century process of urban planning and rebuilding was especially extensive, even though a number of historic buildings have survived in the city, and may still be viewed today.

My path took me via Duesseldorf's Central Railroad Station (Hauptbahnhof ), belonging to the Federal German railroad company, Deutsche Bahn , since I had a matter to attend to in the Ackerstrasse of that city. The functional lines of its existing main building arguably suggest to the vistor that it, too, formed part of the massive post-World War 2 programme of rebuilding that necessarily took place. This was certainly my assumption at the time of my visit.

I was very wrong.

Some history

As I was researching this building's history, I later discovered that the dates of construction for Duesseldorf's Central Railroad Station were actually 1932-1936. The upheavals resulting from the far-reaching 1933-1945 years (usually referred to in Germany as the NSDAP-period) affected the face of urban Duesseldorf greatly. But these occurred just after the essential commissioning, architectural planning and commencement of this building by the former German State Railroad company, Deutsche Reichsbahn .

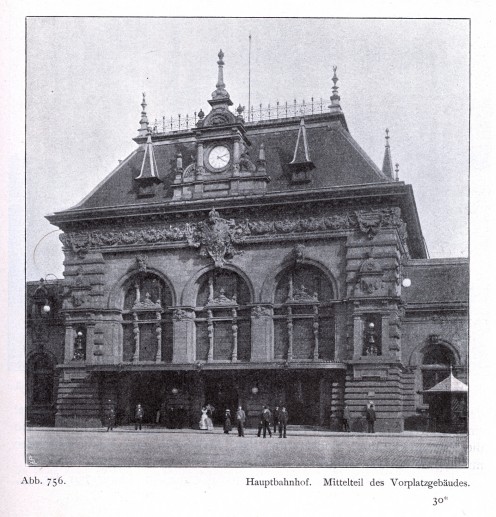

Learning more about the building, I discovered that the style which it reflects is the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit ) or New Building (Neues Bauen ) ideas which were very much in vogue in the Weimar period of Germany (1918-1933). The sheer thoroughness of the way these ideas were taken up is arguably seen in what happened at Duesseldorf's Central Railroad Station. Because in order to erect the current building, a previous building had to be demolished in 1932.

This former building was only 41 years old at the time of its demise. Built in 1891 for the former Prussian state railroad company (1), its style is described as Wilhelmine or German Renaissance, which in 1932 was evidently regarded with little appreciation.

A few reflections

Today, if a building such as Duesseldorf's former 1891 Central Railroad Station needed to be renovated and enlarged, it would probably be carried out while carefully preserving at least the original façade. (Indeed, in Canada, a building with such a façade would probably be viewed as a venerable example of architecture worthy of keeping and enhancing.) My layman's comment about the 1932-1936 building which replaced it would be that it is not unpleasing in itself, and undoubtedly has some architectural merit. But for the 1891 building to be demolished, in order that such a building should replace it, would probably be widely referred to today as an act of architectural vandalism.

However, it is fair to remember that, in the course of about 80 years since the Duesseldorf's current Central Railroad Station was erected, ideas in vogue about architecture have greatly changed and will doubtless continue to do so.

It is also fair to say that, for Germany, the year 1945 was not the only time which marked cataclysmic, historical changes, greatly influencing its culture. 1918, the year of the demise of Imperial Germany, also marked the bringing in of deep, cultural changes, in which the cult of the modern and rejection of old orders, were strong leitmotive (2). It is clearly arguable that this perceived 'modernity' culture influenced the manner in which the architectural merits of Duesseldorf's former 1891 Central Railroad Building were dismissed in 1932 in such a evidently sweeping manner.

Also worth seeing

The Old City Hall (Das Alte Rathaus , distance from Central Railroad Station: 2.7 kilometres) is a well-preserved 16th century building. In front of the Old City Hall is an equestrian statue of Elector Palatine Jan Wellem (1658-1716).

The Rheinturm ('Rhine Tower'; distance: 3.2 kilometres), 240 metres high, overlooking the Rhine River , is a major, local landmark, with an observation deck, and a revolving restaurant.

The St. Lambertus Kirche (distance: 2.4 kilometres) is Duesseldorf's oldest church, dating from the 12th/13th centuries. Its distinctive tower is a conspicuous, local landmark. Notable memorials in the church include one for Duke William of Juelich-Cleves-Berg , patron of Erasmus of Rotterdam (and brother-in-law, through his sister Anne of Cleves , of English King Henry VIII). In this church, the reliquary of St. Apolinaris has for centuries been a place of pilgrimage.

The Neanderkirche (distance: 2.8 kilometres) is a 17th century Baroque church, named for Joachim Neander (1650-1680), prolific author of Protestant hymns, including Lobe den Herrn ('Praise to the Lord').

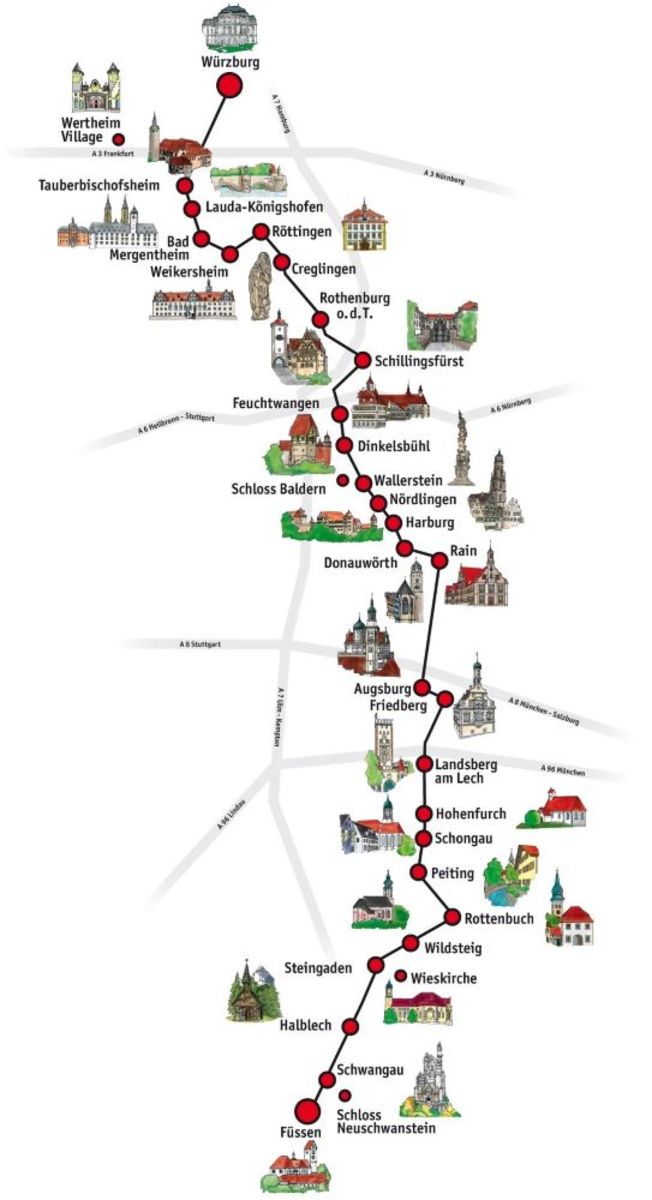

Cologne (distance: 40 kilometres), with its historic, twin spired Cathedral (der Koelner Dom ), has long been among the most well-known places to visitors to Germany.

Aachen (distance: 85 kilometres) has numerous cultural treasures, but these include the monumental Cathedral (Dom ), with its associations with Emperor Charlemagne (circa 742-814) , and the City Hall (Rathaus ), with its impressive façade.

The Royal Air Force Museum , at the former RAF Laarbruch , Airport Weeze (distance: 82 kilometres) has become a favourite for aviation buffs since its opening a few years ago.

Notes

(1) This company managing the former Prussian state railroad was known under various designations; at the time of the erection of the 1891 building it was the Koeniglich Preussische Staatseisenbahnen , then subsequently the Koeniglich Preussische und Grossherzoglich Hessische Staatseisenbahn , and, again, subsequently, the Preussische Staatsbahn , until it was replaced by the Deutsche Reichsbahn .

(2) General acknowledgment is made to a German history course led by Dr. John Sandford at Reading University, attended many years ago. (Any terminological inaccuracies in this article remain mine.)

...

How to get there: Lufthansa flies from New York Newark to Duesseldorf Airport (Flughafen Duesseldorf ; distance: 9.9 kilometres), where car rental is available. The German railroad company Deutsche Bahn (DB) links Duesseldorf Airport to Duesseldorf Central Railroad Station (Hauptbahnhof ). Please check with the airline or your travel agent for up to date information.

MJFenn is an independent travel writer based in Ontario, Canada.

Other of my hubpages may be of interest

- Visiting Bonn, Germany: quiet, university city with a now reduced, Federal vocation

The city of Bonn seems to be going full circle. Having previously been a quiet university city beside the Rhine River, after World War 2 it emerged as the (provisional) capital of the Federal Republic of... - Visiting Lemiers, Germany and the Senserbach: memories and reflections at a Nordrhein-Westfalen vill

When I first arrived at the tranquil village of Lemiers, Germany (today within the borders of Aachen), I did not quite realize what was in store. Defined by the 'Senserbach' Lemiers... - Visiting Vaalserquartier and Dreilaendereck at Aachen, Germany: three countries meet

Aachen's Vaalserquartier is an outlying district of Germany's historic city of Aachen, but a fascinating one. From the built up area comprising Vaalserquartier and Vaals a number of paths lead up by foot... - Visiting Germany's Wemb and former RAF Laarbruch in Nordrhein-Westfalen: borders and history in prox

This article arises out of a visit which I paid to Nordrhein-Westfalen's Wemb (or, more formally, Weeze-Wemb) and to the former British Royal Air Force Laarbruch. The gentle, pastoral scenes in this...