- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

How to Be an Ace

Field Kindley

About World War 1 Ace Field Kindley

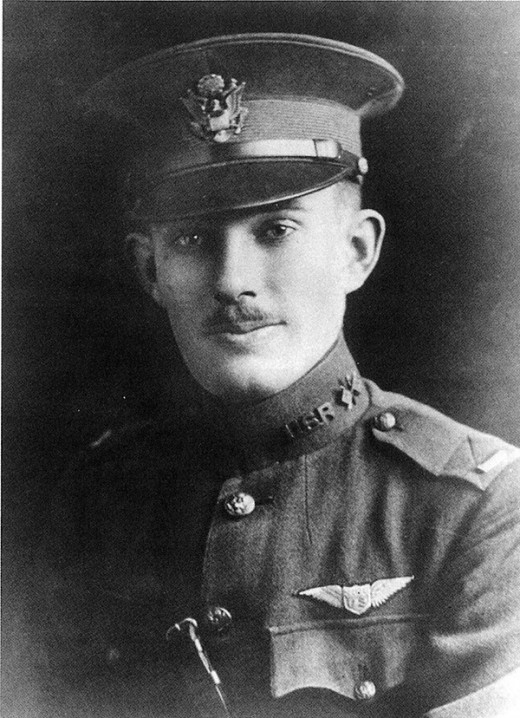

The number one ace pilot for America in World War 1, Eddie Rickenbacker, was previously a race car driver. America’s number four ace pilot (number five, if you count Raoul Lufbery) was previously a movie projectionist: Field Kindley. Yes, that’s written the right way around, though after his death an airfield in the Philippines, and later one on Bermuda, were named Kindley Field in honor of Field Kindley.

One can see some overlap in skill sets between a race car driver and a fighter pilot. But how does a movie projectionist become a top ace? In reading War Bird Ace: The Great War Exploits of Capt. Field E. Kindley, I noticed the author, retired USAF officer Jack Stokes Ballard, had a lot of discussion of the qualities that might predict a top ace. This book should be very interesting to Air Force cadets in general, and pilot candidates in particular, because it is both foundational history of the Air Force and also gives insight into that burning question, “will I be selected for pilot training or washed out?”

Foundations of the Air Force

I discovered this book through the Vintage Aero Flying Museum, which was one of the book’s information sources. Kindley’s name is barely known today, partly because nobody pays attention to number four of anything, but mainly because he died in a postwar flying accident at the age of 23. Otherwise, he seemed on track to become one of the foundational pilots of the Air Force, as he was an ace like Eddie Rickenbacker and promoted aviation through air racing like Jimmy Doolittle. Also, like Billy Mitchell, he stayed in the Army after the war and spoke up for a cabinet-level Department of the Air.

As it was, Kindley put a lot of living in 23 years, and a 23-year-old in those days did not seem as young as now. (Another WW1 pilot at the age of 24 said flying and fighting made him look 40 and feel 90 years old.)

The two Kindley Fields and other places related to Field Kindley

Where Field Kindley grew up, also where there was a Kindley Field named for him.

Site of the second field named for Field Kindley, an airfield used in World War 2.

Kindley Field in Bermuda

![By US Army [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons By US Army [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://usercontent2.hubstatic.com/7378453_f520.jpg)

Not so average

At the time the US entered World War 1, Field Kindley was a movie projectionist from Kansas. After the war, he had the chance to be part of movies about aviation. How many projectionists watch thrillers and imagine themselves as the hero? But then how many of those, within a couple of years, actually become that hero, and get offered a part in a movie?

Actually, Kindley’s life was not as average as that description sounds. He was born in Arkansas, but his mother died before he was 3, and from 7 to 12 he lived in the Philippines where his father was a schoolteacher. Later he returned to the US to live with relatives in Arkansas, while his father stayed in the Philippines. Besides being a projectionist, he was also a part owner of the movie theater, and a successful entrepreneur, recognized for honesty and success.

Kindley joined the Army about a month after the US declared war on Germany. He started in the infantry, but decided the Air Service sounded better.

Many ace qualities were lacking

Kindley had no strong mechanical bent, and no tendency to recklessness or thrill seeking. As a boy, he was not particularly adventuresome or driven. His decisions seemed to be made calmly and thoughtfully. His high school grades were only slightly above average, with no particular strength in math or science, and he quit school before graduating. He played sports, but was not a star. He wasn’t known for hunting or any other involvement with firearms. He could make minor repairs and adjustments to a car or motorcycle, but did not know gasoline motors. Nothing about him showed particular aptitude for aviation.

Ace potential

He did have some promising, though less obvious, characteristics. Kindley was open to making changes in his life, maybe because of the major changes he’d already handled. He was already fairly self-reliant and independent. His world travel was unusual for his generation, and was a good preparation for being sent to Europe. His loose family ties made it easier for him to decide to leave for parts unknown.

Kindley’s country charm (“Everyone liked Field”) helped him both in business and in getting into Air Service leadership positions. His business experience was considered valuable enough to equate to two years of college education. Kindley was curious, always wanting to learn, which was vital in an era when both cars and airplanes were newfangled monstrosities. Finally, he had a toughness and determination that served him well in dogged pursuit of enemies in the air.

Field Kindley and Sopwith Camel

Pilot training

Kindley’s flying training was in England, making him one of the RAF-trained American “War Birds”, and he was complimented on his nerve on his first solo flight. He liked flying, apparently finding it exciting, which it certainly was; he survived various narrow escapes in his training. He was taught formation flying and ground strafing, subjects that didn’t exist a few years before!

He spent some time in spring 1918 ferrying aircraft around Britain and over the Channel. One day Kindley tried to fly the Channel in bad weather (probably because of a French girl he’d met). Experiencing engine problems in 25-foot visibility, he crashed into the white cliffs of Dover. Unlike his aircraft, he survived with no major injuries, and was lucky in how the accident was written up, deemphasizing pilot errors. His commanding officer was protecting Kindley, seeing that his willingness to take a chance and his determination to do a job were qualities badly needed at the front.

Combat flying

In the 148th Aero Squadron, high-school dropout Kindley was among a group of mostly Ivy League graduates. Like 7th-grade dropout Eddie Rickenbacker, he earned their respect with what he did in the air and his eagerness for combat, and he soon became a flight commander. A fellow pilot described Kindley as a born leader without a nerve in his body.

Qualities of a flight commander

A flight commander had a lot to do: watching for enemy aircraft and understanding their strategy, making sure the flight was in formation, trying to get in a good position relative to the enemy, dodging anti-aircraft fire, and when necessary, retreating without leaving anyone behind. Anti-aircraft fire usually missed, but Kindley noted that with the number of shots fired at some pilots, statistics were not in favor of the pilot!

As flight commander, Kindley was a father figure to his pilots. He was noted for planning and concern for his pilots, being more of a team player than most flight commanders, being tenacious and with quick reactions, but also quiet, and level-headed. Even when he was nervous, he appeared cool and deliberate. He was also respected in the enlisted ranks, since he showed appreciation for his mechanics at a time when acknowledging the contributions of others was less expected.

Camels in a row

Ace strategy

Kindley became an ace (five air victories) on September 2, 1918, and ended the war with 12 victories. Different aces had different strategies, some relying on surprise, others relying on dogged tenacity. Kindley was aggressive, getting an enemy in point-blank range before firing. Like many other pilots, he had a mascot, an English bull terrier named “Fokker”.

Field Kindley and "Fokker"

End of World War 1

Pilots often got fatalistic about their own deaths, as the stress of combat and the deaths of friends mounted. They often appeared to live only for the day, because it was a way to hide the fear and sorrow – it was vital to keep the fear from spreading through the unit.

The stress affected Kindley enough that a medical evaluation recommended leave for him, which he got after the war ended. But also after the war he became squadron commander of the 141st Aero Squadron, which even after the war was quite a challenge – how to keep up the morale of a squadron that is not fighting but not yet home?

Aviation after World War 1

As a squadron commander and a top ace, Kindley got to write some of the “lessons learned” from WW1 air combat; lessons which became part of Air Force doctrine. As mentioned before, he was also offered money to make a movie, but didn’t think it would be an ongoing job, and also didn’t think the movie would do justice to aerial combat. He stayed in the Army, and started representing the Army in air races, which helped raise public awareness of flying. (Many pilots in World War 2 were inspired to fly by barnstormers and air racers between the wars.)

However, Kindley didn’t get far in air racing. He survived (with literally only a scratch) a crash in Albany, where there were unexpected air currents - he heroically wrecked his plane to avoid hitting the crowd. In another race from Long Island to San Francisco, he had difficulties and was dropped from the race.

In 1919, Kindley testified for a Congressional hearing about forming a united air service. Saying much the same thing as what Billy Mitchell got in trouble for, Kindley testified that aviation was too big a job for the Army or Navy, and that pilots should be trained and flying in preparation for the next war – in fact, he noted, in the next war, the first battle could be in the air!

Perhaps this hearing was part of why Kindley was reassigned to Kelly Field, at San Antonio. He was to take over command of the 94th Aero Squadron, the one Rickenbacker had commanded (Rickenbacker was now a civilian.)

Sadly, while the base was preparing for a visit by General Pershing, Kindley saw from the air some men near a target for a firing demonstration. He dove down to warn the men away from the area, but after warning them, something happened. The aircraft hit the ground and “War Bird” ace Kindley was killed in a peacetime accident.

War Bird Ace by Jack Stokes Ballard

And much more aviation history

This article has only summarized the discussion about what makes an ace, but War Bird Ace covers many more aviation history subjects. For instance:

- How flying changed during WW1

- How aircraft were used and how they affected the ground war

- Why squadrons flying Camels got most of the missions attacking ground targets

- The Jasta with blue tails that may have been better than Richthofen’s Flying Circus

- How the German air effort managed to stay deadly even as the war drew to a close

This book is great for anyone interested in WW1 aces or Air Force history. It is not long (there isn’t that much recorded information about Kindley) but the book is carefully sourced, and its bibliography itself is a great resource for books on aviation history.