Gay Marriage Gains Ground in America

Philip Chandler July 2014

Gay Marriage Gains Ground in America

GAY MARRIAGE GAINS GROUND IN AMERICA

Although the terms “same-sex marriage” and “gay marriage” are used more or less interchangeably in the debate currently swirling around the nation, this essay uses the latter term, since this issue is of great significance to gay and lesbian Americans. There may well be a small number of cases in which two persons of the same sex who are not gay have chosen to avail themselves of same-sex marriage, just as there are certainly a relatively small number of cases in which two persons of opposite sexes who are not heterosexual have chosen to avail themselves of opposite-sex marriage; such marriages are usually entered into for financial reasons (or in the case of opposite-sex couples, for immigration reasons); but such marriages are very much the exceptions to the general rule, which is that people seek to get married to demonstrate their mutual love and commitment, to support each other emotionally and psychologically, to support each other financially and materially, to pool their resources, to shelter each other and to provide healthcare (and other important benefits) for each other, and to create a secure environment in which to raise children.

Recent judicial and legislative developments in different parts of the country have moved the issue of gay marriage to a position of prominence once again as the debate over gay marriage continues to rock the nation. Some of these developments, discussed in more detail below, have robbed members of the hard right of one of their most potent rhetorical weapons, and have significantly changed the terms of the debate, to the advantage of those who believe that gay marriage should be legalized throughout the nation. In addition to the judicial and legislative developments, the results of a major poll were recently released, showing that attitudes towards gay marriage have shifted dramatically since this issue was first raised in the mid-1990s; furthermore, the change in attitudes has been particularly dramatic over the course of the past three years, and across generations.

On November 18, 2003 the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (SJCM) handed down Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, 798 N.R.2d 941 (Mass. 2003), holding that the existing marriage statute (which recognized only marriages between one man and one women, thus prohibiting the recognition of gay marriages) violated both the due process and the equal protection provisions of the state constitution. Instead of creating a new, “fundamental” right to marry a person of the same sex, this decision held that the prohibition of same-sex marriages lacked a rational basis. This decision immediately became the focus of heated debate and contention, with social conservatives accusing the SJCM of “social engineering” and of “usurping the will of the people” by imposing gay marriage on the state by “judicial fiat”. It did not help that this decision was handed down by a bare majority (the vote was four to three).

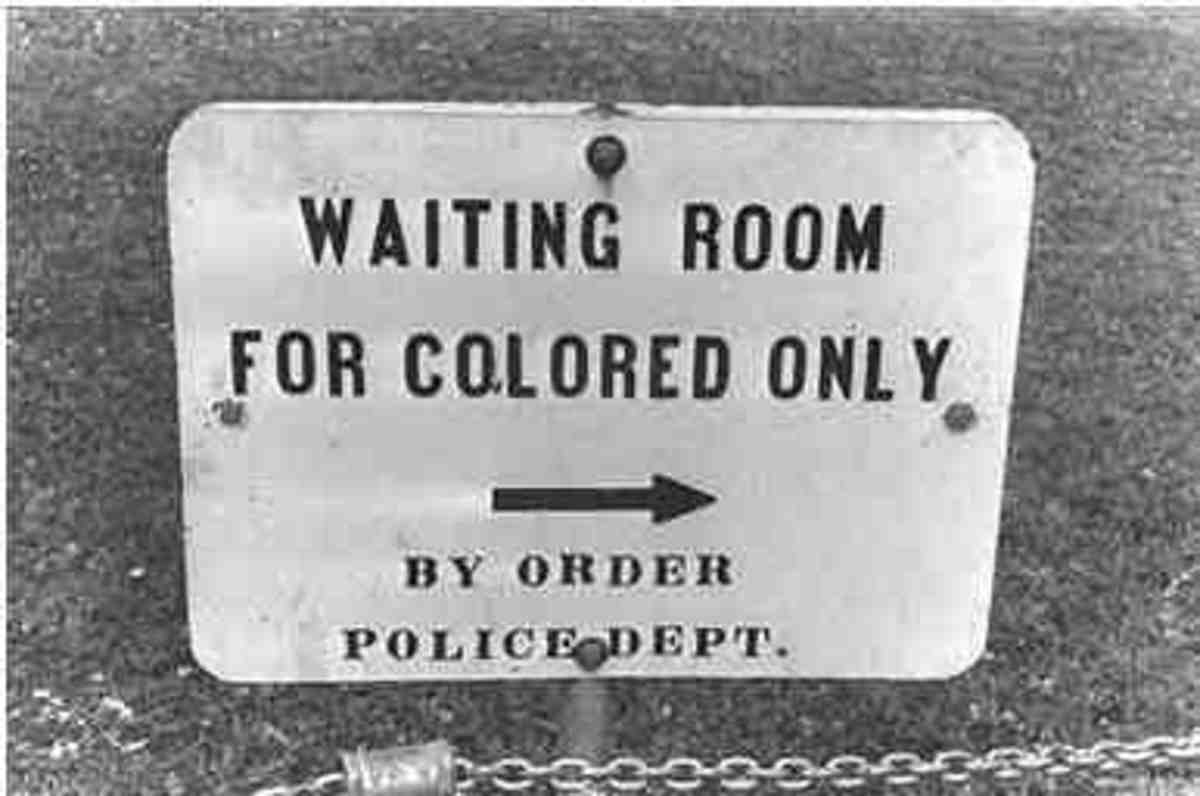

Chief Justice Margaret Marshall authored the majority opinion, which was noteworthy for its strong language. This opinion ended with the following observation: “The marriage ban works a deep and scarring hardship on a very real segment of the community for no rational reason. The absence of any reasonable relationship between, on the one hand, an absolute disqualification of same-sex couples who wish to enter into civil marriage and, on the other, protection of public health, safety, or general welfare, suggests that the marriage restriction is rooted in persistent prejudices against persons who are (or who are believed to be) homosexual.” The majority cited Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) (striking down all state sodomy statutes as applied to consensual sexual activity between adults acting in private settings) no fewer than five times, reiterating the point that whether and how to establish a family is “among the most basic of every individual’s liberty” and reaffirming this groundbreaking precedent. The majority also invoked Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996) to note that “…the marriage restriction impermissibly “identifies persons by a single trait and then denies them protection across the board””. The majority also cited from both federal and state case law to conclude that marriage is a basic civil right “of fundamental importance for all individuals” (citing from Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978)). The majority also cited from Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), in which decision the US Supreme Court invalidated all so-called “miscegenation” statutes that prohibited white persons from marrying non-white persons, holding that such statutes violated both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Justice John Greaney wrote a concurrence agreeing with the result, agreeing with the remedy (expansion of the statute to include gay couples), and agreeing with much of the majority’s reasoning; however, he wrote separately to emphasize his belief that the case should have been decided by employing “strict scrutiny” (the most demanding level of judicial review, reserved for those instances in which the right denied the plaintiff (or otherwise infringed) is considered by the reviewing court to be “fundamental” in nature, or for those cases in which a “suspect class” (discussed later) is deprived of a right by the challenged statute). The state can only meet its burden under strict scrutiny if it can demonstrate that the discriminatory effect of the statute in question promotes a “compelling” state interest, and if the state can also demonstrate that the statute sweeps no more broadly than is absolutely necessary to promote the interest in question (i.e., the statute must be “narrowly tailored” so as to interfere with, or infringe, the right in question in the “least restrictive” manner possible). As a practical matter, the application of strict scrutiny almost always results in victory for the plaintiff and loss for the state, because this standard is so demanding and so difficult for the state to meet. In response to the argument that marriage is, by definition, the union of one man and one woman, Greaney responded:

“To define the institution of marriage by the characteristics of those to whom it always has been accessible, in order to justify the exclusion of those to whom it never has been accessible, is conclusory and bypasses the core question we are asked to decide. This case calls for a higher level of legal analysis. Precisely, the case requires that we confront ingrained assumptions with respect to historically accepted roles of men and women within the institution of marriage and requires that we reexamine these assumptions in light of the unequivocal language of art. 1, in order to ensure that the governmental conduct challenged here conforms to the supreme charter of our Commonwealth. "A written constitution is the fundamental law for the government of a sovereign State. It is the final statement of the rights, privileges and obligations of the citizens and the ultimate grant of the powers and the conclusive definition of the limitations of the departments of State and of public officers… To its provisions the conduct of all governmental affairs must conform. From its terms there is no appeal." Loring v. Young, 239 Mass. 349, 376-377 (1921)”

A carefully orchestrated and well-organized effort to amend the Massachusetts state constitution to prohibit the recognition of gay marriages (which would have had the effect of invalidating the SJCM’s opinion in Goodridge) was launched by the hard right, and both chambers of the state legislature convened towards the end of the 2003 – 2004 session to discuss Goodridge and to hammer out a constitutional amendment. Following a raucous and particularly ugly debate in which the gay community was vilified by the hard right, a narrow majority of legislators approved a compromise constitutional amendment which would have prohibited the recognition of gay marriage but which would also have created a system of civil unions for gay couples. Under Massachusetts state law, any proposed constitutional amendment has to be approved by a joint session of both chambers of the state legislature in two consecutive sessions, requiring that the same proposal be ratified during the 2005 – 2006 session; however, this proposal failed during the 2005 – 2006 session, to the dismay of social conservatives. Animus towards those legislators who refused to vote in favor of the proposed amendment rose to such levels that the writer recalls accusations of bribery, corruption, and even prostitution levelled against those legislators who either refused to vote in accordance with the wishes of the hard right, or who changed their minds across legislative sessions.

Gay marriage has been in existence in Massachusetts for five full years now, and there are currently no serious threats to gay marriage in that state. The people of Massachusetts appear to have accepted gay marriage in that state, and the hard right has made no serious recent attempt to roll back this historic victory for marriage equality.

On July 6, 2006, the New York Court of Appeals – the highest state court in New York – rejected a challenge, on state constitutional grounds, to the opposite-sex only marriage statute (Hernandez v. Robles, 855 N.E.2d 1 (N.Y. 2006)). However, Chief Judge Judith Kaye authored what even opponents of gay marriage considered to be an analytically brilliant dissent, which has been cited extensively by other state high courts that have legalized gay marriage.

On May 15, 2008 the California Supreme Court became only the second state high court in the country to hold that the relevant state constitution was offended by the limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples only. In handing down in re Marriage Cases, 43 Cal.4th 757 (Cal. 2008), this court broke new legal ground. The California Supreme Court became the first state supreme court in the nation to hold, as a matter of law, that gay and lesbian persons comprise a “suspect class” for the purposes of state equal protection jurisprudence. The court held that the prohibition of gay marriage violated both the state constitution’s due process guarantees and the state constitution’s equal protection guarantees. Again, this ruling was decided by a vote of four to three, prompting the usual outcries from conservatives of “judicial tyranny” and “usurpation of the will of the people”.

A “suspect class” is a group of persons who can show a history of purposeful and invidious discrimination, which is triggered by the expression of a characteristic that bears no relationship to the ability of members of the group in question to contribute to society. The characteristic in question is either “immutable”, or changeable only at unacceptable personal cost to members of the group in question; in addition, members of the group in question can demonstrate a history of relative political powerlessness. The reviewing courts typically place much greater emphasis on the first two criteria (the history of purposeful and invidious discrimination, and the fact that the characteristic that triggers this discrimination bears no relationship to the ability of members of the group in question to contribute to society) than it does on the last two criteria (the immutability of the characteristic in question, and the history of relative political powerlessness).

The most obvious examples of suspect classes are racial minorities. A suspect classification is a classification that creates a suspect class. As stated above, any statute that infringes the rights of members of a suspect class, or that creates a classification that proceeds along suspect lines, is automatically subjected to strict scrutiny. Whereas the US Supreme Court recognizes only race, national origin, alienage, and religion as suspect classes, the California Supreme Court became the first state supreme court in the nation to hold, independently, that gay men and lesbians constitute a suspect class under state equal protection jurisprudence. (Note that although the Hawaii Supreme Court, in Baehr v. Miike, 994 P.2d. 566 (Hawaii 1999) held that a state constitutional amendment granting the legislature the power to limit marriage to opposite-sex only couples effectively mooted its earlier holding that the prohibition of gay marriage probably violated the state constitution’s equal protection guarantees, the Hawaii Supreme Court noted, in Footnote 1 of the majority opinion (Baehr, supra) that the Framers of the 1978 Hawaii state constitution had expressly stated that the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation was to be subsumed within the prohibition of discrimination based on sex, requiring that both forms of discrimination be subjected to strict scrutiny; this state high court concluded that the state legislature required that sexual orientation be treated as a suspect classification. Thus, for all purposes other than marriage, gay persons remain a suspect class for the purposes of Hawaii state equal protection jurisprudence.)

The purpose of the identification of suspect classes is to ensure that discrimination against members of “discrete and insular minorities” be subjected to a higher standard of judicial review than mere rational basis review. In a landmark case, United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938), the US Supreme Court noted in a footnote (Footnote 4, which has become one of the most oft-cited footnotes in the US Supreme Court’s history) that there may be some circumstances under which a more searching standard of judicial review than mere rational basis review is appropriate. More specifically, the Court noted that discrimination against “discrete and insular minorities” may be a form of discrimination that should be subjected to a more searching standard of review than mere rational basis review. The Carolene Products Court also expressed concern about “legislation which restricts those political processes which can ordinarily be expected to bring about repeal of undesirable legislation” and implied that it may also be necessary to subject such legislation to “more exacting judicial scrutiny under the general prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment than are most other types of legislation” (an example of such legislation that comes to mind is Colorado’s infamous “Amendment 2”, which was overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court on the grounds that it violated the fundamental right of gay persons to equal participation in the political process (Evans v. Romer, 854 P.2d 1270 (Colo. 1993) and Evans v. Romer, 882 P.2d 1335 (Colo. 1994)); the US Supreme Court affirmed, but asserted that it did so using the rational basis standard of review (Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996)); in fact, constitutional scholars have pointed out that there was really remarkably little difference between the logic adopted by the Colorado Supreme Court and the logic adopted by the US Supreme Court, and several scholars have opined that the US Supreme Court really applied a higher standard of review than mere traditional rational basis review).

In holding that gay persons comprise a suspect class, the California Supreme Court declared that it considered discrimination against gay persons to be as reprehensible and as legally impermissible as discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, or religion. Thus, the California Supreme Court went far beyond finding that the prohibition of gay marriages violated the state constitution; it held that this prohibition was as unacceptable as would be state-sponsored racial discrimination, or state-sponsored religious discrimination. The Court held that any statute that discriminates against persons based on their sexual orientation is presumptively unconstitutional and must be subjected to strict scrutiny.

Opponents of gay marriage mounted an aggressive petition drive and managed to place the question of whether to amend the California state constitution to restrict marriage to opposite-sex only couples on the ballot for the November 2008 elections (where this measure became known as “Proposition 8”). Unfortunately, Proposition 8 passed – but by a very narrow margin (52% to 48%). Between the date on which in re Marriage Cases, supra was handed down (May 15, 2008) and the date of the elections in November 2008, more than 18,000 gay couples obtained marriage licenses and were married in the State of California. The fate of these marriages is now unclear; lawsuits have been filed before the California Supreme Court in an effort to prevent Proposition 8 from taking effect. Most constitutional scholars believe, based on the demeanor and questions asked by the Justices during oral arguments, that the state high court will uphold the 18,000 gay marriages that have already been solemnized, but will permit Proposition 8 to go into effect, barring further gay marriages from being performed in that state. However, another petition that would reverse Proposition 8 is already being circulated and is already gathering signatures to qualify it for placement on the ballot in November 2010. Given the very narrow margin by which Proposition 8 passed, and given the fact that proponents of gay marriage now know and understand the tactics of those who drafted and promoted Proposition 8, it is entirely possible that advocates of marriage equality will succeed in overturning Proposition 8 in November 2010. Should the gay community fail in 2010, proponents of gay marriage will return in November 2012; proponents of gay marriage have indicated that they will continue to fight until Proposition 8 is reversed, or until it is declared unconstitutional by the California Supreme Court.

One aspect of in re Marriage Cases, supra that survived the passage of Proposition 8 was the state court’s holding that gay men and lesbians comprise a “suspect class” for the purposes of state equal protection jurisprudence. This is the first time that any state supreme court has held that gay persons comprise a suspect class absent a legislative declaration to that effect (as occurred in Hawaii, above). Notwithstanding Proposition 8, any state statute or executive policy that adversely impacts gay men and lesbians in the State of California must now survive strict scrutiny in order to survive judicial review. This was the silver lining in the cloud of the passage of Proposition 8.

On October 10, 2008, the Connecticut Supreme Court handed down Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health, SC17716 (Conn. 2008). This was an unusually intricate, scholarly, and lengthy opinion, also decided by a four to three vote. The majority concluded that gay persons today possess less political power than women possessed back in the 1970s, when the US Supreme Court first heightened the level of scrutiny that it applied to legislation that discriminated against women. The US Supreme Court applies what is known as “quasi-strict scrutiny” to statutes and policies that adversely impact the rights of women, holding that women constitute a “quasi-suspect” class for the purposes of equal protection jurisprudence (see Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973)). Like the California Supreme Court, the Connecticut Supreme Court examined the four factors that are implicated when a determination is made that a class of persons constitutes a suspect class; however, the Connecticut Supreme Court declined to reach the question of whether gay persons comprise a suspect class for the purposes of state equal protection jurisprudence, holding that the opposite-sex only marriage statute could not survive quasi-strict scrutiny, or intermediate-level review (this level of review falls between strict scrutiny and rational basis review). When a statute is examined under quasi-strict scrutiny, it will only survive such review if the state can demonstrate that the legislation in question is substantially related to an important state interest (as opposed to rationally related to a legitimate state interest (rational basis review) or narrowly tailored so as to promote a compelling state interest in the least restrictive manner possible (strict scrutiny)). As is the case when a statute is subjected to strict scrutiny, the burden once again falls to the state to demonstrate that the legislation in question is not unconstitutional; however, the test is not quite as rigorous or as narrow as is the case under strict scrutiny. Having determined that the opposite-sex only marriage statute could not survive quasi-strict scrutiny, the court correctly concluded that it was unnecessary to reach the question of whether or not it could survive strict scrutiny. This is consistent with the doctrine of avoidance, which counsels that a court of equity should decide the case before it on the narrowest possible constitutional grounds, and not reach issues that do not have to be reached in order to resolve the case before it. If a statute cannot survive equal protection review under quasi-strict scrutiny, then it certainly cannot survive review under strict scrutiny, because the latter test is an even more demanding standard of review than is the former test.

The Connecticut Supreme Court held that gay persons comprise a quasi-suspect class, on the same level for the purposes of equal protection analysis as women. The court made extensive findings of fact to support this conclusion. The court held that the prohibition of gay marriage violated the state constitution’s equal protection guarantees.

The Connecticut state governor soon indicated that she would not support efforts to amend the state constitution to prohibit gay marriage, and state House and state Senate leaders indicated that there was insufficient political will to consider a serious effort to amend the state constitution to prohibit gay marriage. Furthermore, Connecticut does not permit direct voter initiatives such as that which was invoked to pass Proposition 8 in California, and the earliest that a state constitutional amendment could be considered under the usual procedures for amending the state constitution would be in November 2012.

Legislation was soon passed to implement the Connecticut Supreme Court’s ruling, and the first gay marriages were performed on November 12, 2008.

On April 3, 2009, the Iowa Supreme Court handed down a unanimous (seven to zero) opinion authored by Justice Cady, holding that the prohibition of gay marriage violated the equal protection guarantees of the Iowa state constitution. This ruling was hailed by many constitutional scholars as a model of logic and clarity. Like the Connecticut Supreme Court, the Iowa Supreme Court held that the Iowa statute limiting marriage to opposite-sex only couples violated the Iowa state constitution’s guarantees of equal protection. The court’s ruling became effective on April 27. The speaker of the state House and the state Senate majority leader both indicated that they welcomed this decision, and Iowa’s Governor Chet Culver has expressed his reluctance to support amending the state constitution in a manner that the state high court has declared to be unlawful and discriminatory. Like Connecticut, it is not possible to amend the Iowa state constitution through the voter initiative process, and for all practical purposes, the earliest that a state constitutional amendment can possibly be contemplated will be in November 2012.

The Iowa Supreme Court also used intermediate-level review (quasi-strict scrutiny) to strike down the opposite-sex only marriage statute, holding that gay Iowans constitute a quasi-suspect class for the purposes of state equal protection jurisprudence. The Iowa Supreme Court appeared to accept much of the logic embodied in the California and Connecticut rulings, and also cited extensively from the dissenting opinion authored by Chief Judge Judith Kaye, of the New York Court of Appeals, in the New York gay marriage case (Hernandez v. Robles, supra).

On April 7, 2009, Vermont became the fourth state in the nation to legalize gay marriage (the fifth if California is included). Furthermore, the decision by the Vermont state legislature to legalize gay marriage did not follow judicial intervention, as had occurred in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Iowa. Instead, the state legislature overrode the Republican governor’s veto of a proposed measure to legalize gay marriage. Under Vermont state law, a two-thirds vote of both chambers of the state legislature is necessary in order to override a governor’s veto. It is therefore not overstatement to declare that Vermont became the first state in the nation in which, without judicial intervention, the state recognized gay marriage; furthermore, the legislative vote was overwhelming.

Social conservatives found themselves robbed of one of their most potent rhetorical weapons. Up until this vote was taken by the Vermont state legislature, social conservatives had been able to argue that the legalization of gay marriage had been “forced” on those states that recognized gay marriage by judicial fiat. Maggie Gallagher – President of the “National Organization for Marriage” (NOM) – had written numerous columns and articles in which she had opined that gay marriage had been forced on the American people by state supreme courts, and that no state legislature had voted to recognize gay marriage of its own accord. This argument collapsed in the face of the Vermont legislative victory; nevertheless, Gallagher and her associates were still able to point out that “civil unions” had been implemented in Vermont only following a Vermont Supreme Court decision in 1999 (Baker v. Vermont, 744 A.2d 864 (Vt. 1999)). Members of the “Family Research Council” (FRC) were apoplectic following the passage of gay marriage in Vermont, and declared on the FRC Web site that this victory for marriage equality was a mere aberration.

Then, on May 6, 2009, the governor of Maine signed into law a bill passed by the state legislature legalizing gay marriage in that state. This bill also contained a measure reaffirming the constitutional principle of separation of church and state, clarifying that no church would be forced, under the new law, to recognize gay marriages or to perform gay marriages. Opponents of gay marriage reacted blindly and instinctively, and have vowed to place a measure on the ballot in November 2009 or June 2010 that would withdraw the right to marry from gay people. (Maine is the only New England state that permits legislation to be withdrawn by a so-called “people’s veto”.) However, activists for marriage equality have learned from their experience in California, and public opinion has also changed dramatically over the course of the past few months.

Last week (ending Friday May 15), New Hampshire governor John Lynch indicated that he will sign a measure to legalize gay marriage in that state, provided the measure contains language similar to that included in the Maine measure, reaffirming that churches will not be forced to perform or to recognize gay marriages against their will, and reaffirming the distinction between religious marriage and civil marriage. The state legislature responded immediately by drafting the required language, which is expected to be sent back to the governor for his signature later this week. The hard right is furious; the New Hampshire measure cannot be undone by a “people’s veto” and it is no longer possible to argue that the vote in favor of gay marriage was an “aberration”, given the fact that Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont have all voted in favor of gay marriage. Gone forever is the argument that gay marriage is being forced on the American people by the courts. The very terms of the debate have changed, with right-wing organizations accusing the New Hampshire governor of misleading the people of New Hampshire.

On Thursday April 16, New York Governor David Patterson introduced a bill to legalize gay marriage in that state. The state Assembly has since passed this measure, which is now headed to the state Senate. In the interim, Patterson has ordered all state agencies to recognize the validity of gay marriages entered into in jurisdictions where gay marriage is currently legal (including other New England states as described above, and including Canada). Also, New York courts have repeatedly ruled that same-sex marriages conducted in states where they are legal must be recognized by the State of New York.

On Tuesday May 5, the District of Columbia Council overwhelmingly approved a bill to recognize gay marriages entered into in jurisdictions where gay marriage is currently legal (the vote was 12 to one). The Mayor, Adrian M. Fenty, has indicated that he will sign the bill into law.

Public opinion relative to this issue of gay marriage has shifted sharply over the course of the past 15 years. Back in 1996, only 27% of subjects polled believed that gay marriage should be recognized as valid. By 2005, that figure had increased to 39%. A recent poll on April 30, 2009 by ABC News / Washington Post found support for allowing same sex couples to marry in the United States ahead of opposition to it for the first time, with support at 49% and opposition at 46% while those with no opinion on the matter was at 5%. In addition, 53% believe that gay marriages performed in other states should be legal in their states. Among Democrats, 62% are in favor of gay marriage while 74% of Republicans are opposed, with 52% of Independents in favor of gay marriage.

Support for gay marriage is also sharply divided across generations, with younger subjects being much more likely to approve of gay marriage than older subjects. According to a CNN / Opinion Research Corporation poll released on May 4, 58% of Americans aged 18 to 34 years old believed that gay marriage should be recognized as valid, with this number dropping to only 24% of Americans aged 65 and older. Population dynamics all but guarantee that this shift will continue, and that in years to come, support for gay marriage will continue to climb. Bluntly stated, older people die, whereas younger people carry forward more enlightened attitudes towards gay marriage. This is already reflected in the profound changes that have occurred in American society over the course of the past two decades. In 1986, half of the states had laws on their books that prohibited gay Americans from having sex, even in the privacy of their own bedrooms. This number had dropped to about 14 states in 2003, when the US Supreme Court handed down Lawrence v. Texas, supra, striking down all sodomy statutes as applied to consensual gay sex between adults acting in private. In 1999, the State of Vermont made history when it became the first state to craft civil unions in response to a court order (Baker v. Vermont, supra). Today, in addition to the states that have legalized gay marriage as discussed above, the following states recognize civil unions or domestic partnerships that include some or all of the rights, at the state level, of marriage: New Jersey, Oregon, California, Washington, Maryland, and Colorado.

Despite vehement and heated opposition from the hard right, the number of states that recognize gay marriage continues to climb. The road to equality will not be smooth, and there are bound to be setbacks such as occurred in California with the passage of Proposition 8 in November 2008. However, the days in which the very term “gay marriage” evoked laughter or contempt have long since faded into history, and the movement for marriage equality is clearly gaining traction with mainstream America.

PHILIP CHANDLER

Pet Shop Boys -- Suburbia

Justice at Last -- Gay Equality in America

- Justice at Last -- Gay Equality in America

Gay Equality, the Right to Privacy, and Substantive Due Process: this essay discusses the US Supreme Court decisions that created and expanded the right to privacy, and discusses the cases of Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) and Lawrence v. Texas (2003)...

Gay Rights in America

- Gay Rights in America

This essay describes the manner in which gay sex between men is singled out for harsher treatment by many heterosexual men than is gay sex between women. This essay also discusses US Supreme Court decisions and the impact of gay marriage on religion

Gay Marriage in America (The Gathering Storm)

- Gay Marriage in America (The Gathering Storm)

This essay discusses the current status of gay marriage in America, and reveals the desperation underlying the "National Organization for Marriage" and the $1.5 million advertisement ("The Gathering Storm") (which is actually funny!)...

The Federal Courts, Gay Rights, and the People

- The Federal Courts, Gay Rights, and the People

This essay discusses the role of the federal judiciary in our system of government, and explains the concept of judicial review...

The Supreme Court, Gay Rights, and Lawrence v. Texas (2003)

- The Supreme Court, Gay Rights, and Lawrence v. Texas

This essay discusses the US Supreme Court and the damage it did to gay Americans in handing down Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), as well as the manner in which this Court overruled Bowers and apologized to gay Americans in Lawrence v. Texas (2003)...

Gay Americans and the Federal Hate Crimes Act

- Gay Americans and the Federal Hate Crimes Act

This essay discusses the truth behind the lies told about the proposed federal hate crimes act, and presents a truthful analysis of the real impact that this measure would have on religious bodies and individuals (it would have no impact)...

Gay Americans and the US Supreme Court

- Gay Americans and the US Supreme Court

This essay discusses the homophobia that informed the US Supreme Court decision Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), and how gay Americans turned to state supreme courts to strike down sodomy laws until the US Supreme Court handed down Lawrence v. Texas (2003)

Religion, Gay Americans, and the Law

- Religion, Gay Americans, and the Law

This essay discusses the impact of high court decisions upholding laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation on religious organizations that offer public services (and are thus bound by anti-discrimination statutes)...

Homophobia -- Fear and Loathing in Florida

- Homophobia -- Fear and Loathing in Florida

This essay discusses the behavior of school officials at Ponce de Leon High School, and the manner in which the school principal trampled the First and Fourteenth Amendment rights of gay and gay-supportive students at this school...

Gay Equality, Homophobia, and Another Country

- Gay Equality, Homophobia, and Another Country

This essay discusses and compares social and legal attitudes towards homosexuality in the US and the UK, emphasizing the greater degree of acceptance of gay persons in the UK...

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

- Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

This essay debunks the claims made by Paul Cameron and other right-wing commentators, who claim that gay men have shorter lifespans that straight men, that gay men suffer more diseases, etc.

Indiana Disgraces America (Homophobia)

- Indiana Disgraces America (Homophobia)

Megan Chase -- a sophomore at Woodlan Junior-Senior High School in northeastern Indiana -- wrote an article stressing the need to refrain from judging other people merely because they are different. The school newspaper's advisor...

Mormons Meddle and Destroy Marriage

- Mormons Meddle and Destroy Marriage

This article discusses the manner in which members of the LDS participated in the campaign to pass Proposition 8 in California, thereby nullifying the effect of the California Supreme Court decision legalizing gay marriage in that state...

Loving the Sinner but Hating the Sin (But What is the Sin?)

- Loving the Sinner but Hating the Sin (But What is the Sin?)

This essay debunks the illusion that is is possible for a person to love gay people but not the actual expression of their sexual orientation; the one is inextricably intertwined with the other, just as a person's race is an indelible part of him...

I Feel, Therefore I Hate (Internalized Homophobia)

- I Feel Therefore I Hate

This essay discusses the evidence that homophobic men are often struggling with their own sexual orientation, and are often closeted homosexuals...

California Gay Marriage Case

- California Gay Marriage Case

This essay was written BEFORE Proposition 8 was enacted; it discusses in greater detail the legal analysis invoked by the California Supreme Court majority in the historic gay marriage case (in re Marriage Cases, S147999 (2008))

What a Fool Believes

- What a Fool Believes

This article discusses the belief of South African ex-President Thabo Mbeki (and other AIDS / HIV denialists) that HIV does not cause AIDS, and the horrific consequences that flow from this irrational belief to that nation's infected citizens...

Initial Victory in California (Discussion of the Court's Reasoning)

- Initial Victory in California

This essay was written BEFORE Proposition 8 was enacted; it discusses the legal analysis invoked by the California Supreme Court majority in this historic gay marriage case in that state (in re Marriage Cases, S147999 (2008))...