- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Ancient History

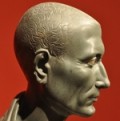

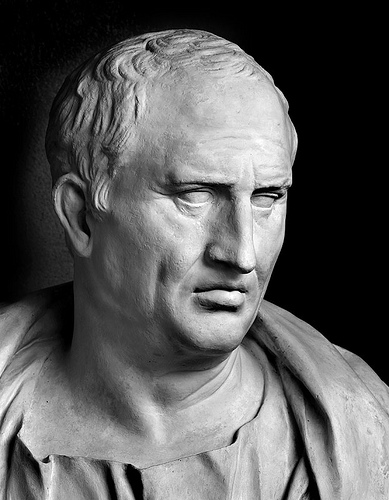

Cicero: Last Defender of the Roman Republic

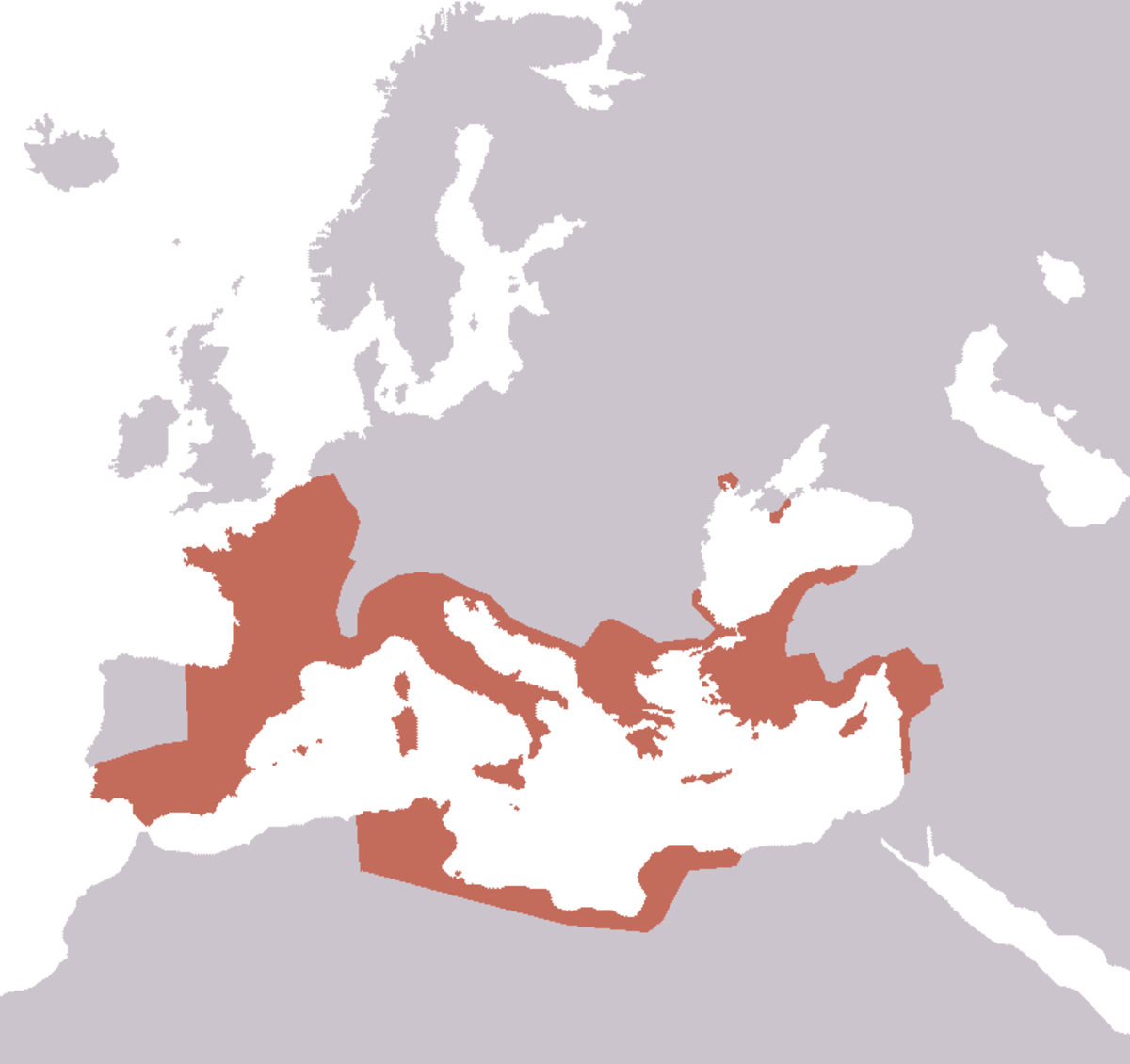

The deed had been done. The “Dictator,” as Julius Caesar had come to be called, lay dead at the feet of a disgruntled Senate. The main instigator of the assassination, Brutus, raised his dagger and saluted the fleeing Cicero on the “recovery of freedom.”[1] This so called freedom had been Cicero’s life mission. He made many contributions to the Roman society, many of which have been passed down to modern society. These contributions span the areas of law, oration, politics, and philosophy.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in Arpinium, a hill town about seventy miles south of Rome, in the year 106 BC.[2] Cicero fell in love with all things Greek at an early age, and this tendency is evidenced throughout the rest of his life. He was seen as a gifted student in his early years and studied under the tutelage of a learned Roman named Scaevola. He spent most of his time learning from Scaevola at the house of Crassus, and in Crassus’s house Cicero met a young Julius Caesar. Cicero also befriended a boy named Titus Pomponius while studying at the house of Crassus. It is from the letters between Cicero and Titus, who later called himself Atticus, that we gain a personal insight into Cicero’s mind.[3] Atticus published the letters from Cicero after Cicero’s death, and many of these still remain. Cicero lived his teen and early adult years under the regime of Sulla and its proscriptions. This environment largely affected Cicero’s views of government and politics. Plutarch says of this period, “But perceiving the commonwealth running into factions, and from faction all things tending to an absolute monarchy, he betook himself to a retired and contemplative life, and conversing with the learned Greeks, devoted himself to study.”[4] During this time he diligently studied the Greek orators, and from this study he became known as the greatest orator that Rome ever saw. Once the proscriptions ended, Cicero began his public career. He began by taking briefs at the law court in the Forum.

Cicero made his name known by his performance in the Forum’s court. His first famous case was his defense of Sextus Roscius. He openly opposed a favored friend of Sulla, and this is what gained him fame. It is also why Cicero left on a tour of Greece and Asia Minor soon after. His most famous law case was his accusation of Catilina, who attempted to take over the Roman state by force. Cicero had five Roman citizens executed without trial, but he was so popular that very few opposed his actions. A very far-reaching trial saw Cicero testify against a man named Clodius. During his time at law, Cicero held most of the major offices of theRoman Republic. He became Quaestor of Sicily in 75, Aedile in 69, Praetor in 66, and Consul in 63. He used his popularity gained as a successful lawyer to springboard his political career.

Cicero vowed to maintain a stable Republic, for he had seen what anarchy was like. “He stood for the rule of law and the maintenance of a constitution in which all social groups could play a part.”[5] Cicero’s main goal during his consulship was to strengthen the Senate in anticipation of Pompey’s return from Asia. The fear was that Pompey would use his popularity and military strength to gain an upper hand in Rome. This fear was unfounded however, and Pompey disbanded his army before returning to Rome. Caesar had become extremely powerful as well and in 60 BC, he made an agreement with Pompey and Crassus that effectively gave them control of Roman politics. They tried several times to gain Cicero’s allegiance, but Cicero refused their offers. He remained loyal to the Senate, and to his ideals of a constitutional Republic. His refusal to join the first Triumvirate ultimately led to his exile from Rome. Clodius, the man whom Cicero had testified against earlier, was made tribute of the people by Caesar. In his new position, Clodius gained his revenge and passed a law exiling all people responsible for unlawfully executing a Roman citizen. This was aimed directly at Cicero for his role in the Catiline conspiracy while he was Consul. Cicero went into exile for two years, but was eventually recalled by a reluctant Caesar.[6] Following his return from exile, Cicero was more cooperative with the Triumvirate. He openly befriended Pompey and sought to gain Pompey’s allegiance and cooperation with the Senate. He sought to be “a disinterested mediator and bent all his efforts towards reconciling”[7] the various sects within the Roman political scene. The time was past, however, when he could save the Republic by his actions in government. He resorted to writing books as a means of carrying on his ideals.

During the times of his political inactivity, Cicero devoted much time to writing. He wrote on a wide range of topics including rhetoric, politics, law, and philosophy. He largely influenced European culture by his translations of Greek philosophical works. He wrote many essays which adapted the Greek philosophers that had captivated him at a young age. He wrote to Atticus, “They [essays] are mere drafts, produced with little labor: I contribute only the words, of which I have a great abundance.”[8] The death of his only daughter, Tullia, in 45 BC pushed Cicero into a deeply depressed state. It was during this time that he wrote a majority of his original philosophical works, as well as his works that made the arguments for the various veins of philosophical thought (i.e. Epicureanism, Stoicism, or Academicism). His philosophical contributions were more appreciated after his death than they were during his life.

Following Caesar’s defeat of Pompey, Cicero was distanced from political activity. He was successful in gaining pardons for many of those who fought with Pompey during the Civil War.Brutus and Cassius were among those who were pardoned. Although Cicero was sometimes consulted on political matters, it was during Caesar’s rule that he spent the most time on his philosophical pursuits. Caesar’s assassination at the hands of Brutus, Cassius, and the Senate, was largely applauded by Cicero.[9] His complaint was that they should have killed Antony as well, in order to regain sole power for the Senate. When Octavian was announced as Caesar’s heir, Cicero began to form a line of attack that would gain the Senate back its power. He thought they could use the young Octavian to defeat Antony, Caesar’s self-proclaimed political heir, and then dump him once the threat of another dictator had been averted. What no one, including Cicero, would expect was that Octavian and Antony would reach a power-sharing agreement. The Second Triumvirate immediately initiated a Sulla-like proscription, and Cicero was at the top of the list because of his obvious pro-Republic sentiments. He was captured and killed in 43 BC. His head and his right hand were nailed to the rostrum in the very Forum where Cicero had made so many brilliant speeches and cases. It is also known, however, that Octavian, later Augustus, recognized Cicero as a brilliant and influential man, and regretted that Antony had been so bent on his death.

Cicero’s legacy as a multifaceted individual is one of the most known and most influential of the Roman Republic. He made many contributions to many fields and his long-lived fame is an obvious mark of his influence. Plutarch tells this story: An aged Augustus happens upon his grandson reading a volume of Cicero. The boy tries to hide the book, thinking his grandfather to be loath of Cicero’s memory. The emperor, however, takes up the hidden book, reads it for a length of time and remarks of its author, “An eloquent man, my child, an eloquent man, and a patriot.”[10]

[1] Anthony Everett, Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician (New York, Random House, 2003), 269.

[2] J. L. Strachan-Davidson, Cicero and the Fall of the Roman Republic (London, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1925), 3.

[3] Gaston Boissier, Cicero and His Friends (New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, n.d.), 123.

[4] Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives. The Translation called Dryden’s. Corrected from the Greek and Revised by A.H. Clough, in 5 volumes (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1906). Chapter: CICERO.< http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/1775/93972 (accessed on 29 November 2009).

[5] Anthony Everett, Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician (New York, Random House, 2003), 95.

[6] Antony Kamm, The Romans: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 2008) , 38.

[7] Anthony Everett, Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician (New York, Random House, 2003), 202.

[8] Moses Hadas, The Basic Works of Cicero, Edited, with an Introduction and Notes by Moses Hadas (New York: The Modern Library, 1951), xiv.

[9] M. Cicero, A Letter to Basilus, published in The Basic Works of Cicero , (New York: The Modern Library, 1951.), 418.

[10] Anthony Everett, Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician (New York, Random House, 2003), 325.