- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Ancient History

Julius Caesar: Rebellion and Civil War

Face of the Enemy

Revolt in Gaul

Julius Caesar returned from his rather ill conceived invasion of Britain in 53 BC to a Gaul that was supposedly pacified, but instead was ripe for rebellion. While he was still crossing the channel, his winter camps positioned near Liege were attacked and subsequently annihilated by the local Eburones tribe led by Ambiorix. Shortly afterwards the Nervii drawing on inspiration from seeing Romans broken and battered, also rose in revolt and would have destroyed a Roman camp if not for Caesar’s timely intervention. He was forced to raise two more legions and borrow another from Pompey. More bad news arrived, when he learnt that his beloved daughter Julia had died in childbirth, as you can imagine Caesar was beside himself with grief, but the grief Pompey felt was just as great, despite the fact that the marriage had been borne out of politics, he had remained a devoted husband.

Julius Caesar spent the following year launching strikes against more rebel tribes. He managed to catch the Nervii unaware and force them to surrender. Then he wheeled his legions north and struck against the Eburones, although it has to be said that he relied more on neighbouring, friendly tribes to carry out the deed for him. He instructed them ‘to wipe out their race and name as punishment for their crime’. The friendly tribes massacred their neighbours without mercy thus sparing Caesar and his legions from having blood all over their hands. Ambiorix though, managed to escape and was never captured. Caesar had managed to regain some sort of control over the situation, but it was obvious that more work needed to be done.

Meanwhile around a thousand miles away at Carrhae on the Turkish-Syrian borders, his long time ally Crassus and his army were annihilated by Persian forces. Crassus’ death, coupled with the loss of Julia severely ruptured Caesar’s and Pompey’s relationship, it could be said that the loss of Crassus made the inevitable showdown between the two Roman heavyweights inevitable. Even so, both men were keen to show that recent events had not changed things and both went about their business in the usual way.

More on Julius Caesar

Anarchy in Rome

While Caesar was attempting to regain control of Gaul; Pompey was facing his own problems in Rome, in fact the word problem is an understatement; anarchy might be a better description. The spark was set when a Senator called Clodius, whom you might remember as Pompeia’s lover was murdered. The prime suspect was long time rival, and fellow Senator Milo. The initial spark manifested into a pitched battle just outside Rome by rival gangs of thugs. During Clodius’ funeral, widespread rioting broke out, culminating in the burning down of the ‘Curia’ or Senate house, the remnants were used as a pyre for Clodius’ cremation.

Hastily the Senate awarded Pompey emergency powers, affording him the title of dictator. By using his new found authority, he helped restore order, by treating Rome as if it were some far flung turbulent province. As a result of the riots, the existing courts were simply not able to deal with the growing crisis, so Pompey personally passed a bill ‘de vi’ or ‘on violence’ that gave him the authority to bring Milo to justice. He was put on trial, but was unsuccessfully defended by old friend Cicero and consequently sent into exile.

The loss of Crassus and the crisis in Rome may have brought a sense of prospective to Pompey; that can be the only explanation behind having his tribunes sponsor a law that allowed Caesar to stand for Consul despite being absent from Rome, the irregularity committed by Pompey was huge, in fact it violated the Roman constitution. Usually if a general wanted to run for Consul, he would have to lay down his command and return to Rome as a private citizen. However, it did not take long for Pompey to consider the implications of the law he passed, he announced soon after that any prospective candidates would have to announce their intentions in Rome itself; he also took the time to extend his own governorship over Spain by a further five years.

Caesar also took measures to try to heal the crumbling relationship by offering to divorce new bride Calpurnia and marry Pompey’s daughter. Pompey scoffed at the offer and instead decided to get married himself to the daughter of Caesar’s bitter rival, Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio. Caesar responded to the move by acquiring the services of Scribonius Curio as tribune to veto any discussion relating to choosing his successor to command Gaul.

The Man Who Stood up to Caesar

Alesia

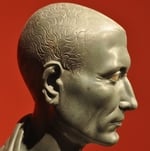

Vercingetorix

In 52 BC most of Gaul rose in revolt, uniting behind a young charismatic man called Vercingetorix, whose name means ‘victor in 100 battles’. He was the leader of a tribe called the Arverni that dwelt in a region, known today as Auvergne. Vercingetorix cleverly rationalised that by cutting off the Romans food supply he could secure victory without having to resort to much brute force. The strategy worked magnificently and Caesar suffered a crushing and humiliating defeat at Gergovia. Finally, by demonstrating the ability to utilise long term strategy, the Gauls had finally secured a victory. Upon hearing the news of Caesar’s defeat, the Aedui, previously allied to Rome decided to side with Vercingetorix, realising at last that the Romans cared not for the well being of the tribes, rather their own glory.

Caesar shaken, but not stirred by the defeat at Gergovia responded with his typical enterprise and daring by hiring a force of German cavalry, narrowly escaping an ambush and driving the Gauls back towards the natural fortress of Alesia. The imposing fortress extended around 500 feet in their air and was well defended. Caesar knew that an all out assault was out of the question so elected to surround it in order to starve Vercingetorix into submission. He had his legions construct eight bases around the perimeter, and also laid a defensive cordon stretching for eleven miles, as well as digging trenches and setting up concealed booby traps filled with wooden spikes and iron objects. Later, he learnt that a relief army was on its way, so he hastily laid another defensive cordon stretching for fourteen miles in the other direction.

The Gauls realised that they were boxed in, and resolved to execute the only strategy left to them, attack. Despite being surrounded by Gauls on both sides, Caesar repulsed attack after attack and scored an outstanding victory. The German cavalry played a huge role by attacking and harassing the Gauls from the rear. Caesar claims in his commentaries that he was outnumbered five to one, but it’s important to take such claims with a pinch of salt.

Despite the victory at Alesia, the unrest continued into the following year. The final engagement took place at another hill fortress called Uxellodunum, which Caesar managed to capture by successfully diverting its water supply. Upon capturing the fortress he ordered his men to chop the right hands off, of all the men captured. Apparently this rather gruesome act was done not out of vengeance or malice but rather to speed up the end of the rebellion. Caesar then imposed a relatively fair settlement by allowing the Gauls to collect their own tribute and also decreeing that their tribal institutions were to remain intact. Incidentally he christened the Gauls who aided him during the revolt ‘Julius’.

The conquest of Gaul was achieved through a clever series of masquerades that allowed Caesar to play one tribe off against the other. Ultimately of course, the invasion and conquest of Gaul was carried out for the simple reason that he wished to enhance both his political and military reputation. He cared little for the welfare of the region, which he exploited mercilessly for his own personal enrichment. Like almost all Romans, there was nothing endearing or romantic about the Gallic culture, to them they were savage barbarians that deserved to be conquered.

By today’s standards Caesar’s actions would undoubtedly mark him out as a war criminal; his crimes against humanity were enormous even by contemporary standards. The Gauls, after all posed no immediate threat to Rome, and yet in just six short years, more than sixty Gallic tribes lost their independence, others were wiped off the face of the Earth completely. According to Plutarch, before the arrival of the Romans, more than six million people lived within Gaul’s boundaries. In six years, a million were dead, and another million had been enslaved. The fact that Caesar exaggerated the figures serves as an insight into his mind, to him the staggering loss of life was justified. Vercingetorix was captured and held for six years, purely so that Caesar could parade him in a triumph before having him garrotted afterwards. It seems strange to me that Caesar is often depicted as a hero, if he had committed the actions described here in the 20th century, he would stand alongside Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, Mao and Idi Amin as some of the vilest men in history, and yet Shakespeare elected to immortalise him in a play still revered and idolised today.

The Protagonists

The Rubicon Bridge Today

Caesar vs. Pompey

A tense atmosphere descended on Rome when the tribune Scribonius Curio put a motion to the Senate recommending that both Caesar and Pompey be relieved of their commands. Unsurprisingly the Senate voted overwhelmingly in favour of the motion. However, instead of simply accepting the vote and informing both men of the decision, the Consul Claudius Marcellus worked the Senate into a state of hysteria and panic by ‘confirming’ a rumour that Caesar had left Gaul and begun marching towards Rome. Accompanied by the two Consul candidates for the following year, he approached Pompey with a sword, placed it into his hands, and conferred on him the command of two legions that had been originally assigned to Caesar; Pompey was now charged with the defence of the city.

Over the course of the next month, the Senate attempted to negotiate a settlement in order to avert a civil war, but all were met by simple, flat refusal by Pompey. On the 1st January 49 BC, the tribunes Marcus Antonius, otherwise known as Mark Antony and Cassius forced newly elected Consul Cornelius Lentulus Crus to read a letter written by Caesar outlining his desire to serve the state, and also pointed out that he had been given the right to stand for Consul despite not being in Rome. He made a simple proposal, either that he be allowed to keep his provinces until after the elections or that both he and Pompey should relinquish their commissions simultaneously; any refusal was met with a simple alternative, civil war against Pompey.

The proposals in Caesar’s letter should have been put to the vote, but Lentulus refused to consider the matter and instead went ahead and declared Caesar to be an enemy of the Republic, however, the motion was vetoed by Mark Antony. The senate was now deadlocked, negotiations continued over the next week. On the 7th January Lentulus managed to persuade the Senate to pass the ‘senatus consultum ultimum’ or ‘last decree of the senate’ essentially the decree acted as an instruction to ensure that no harm should befall the Republic, in other words they issued an ultimatum to Caesar. The tribunes loyal to Caesar had no choice but to flee Rome in disguise and join him in the north.

Caesar had been presented with two clear operations; either surrender his legions and accept his fate, whether it be exile or execution, on the other hand he could march on Rome, just as Sulla did. He had received news of the Senate’s decision on the 10th January near Ravenna, judging by his own words he’d ‘been waiting for an answer to his very mild demands in the hope that the people’s natural sense of justice would bring the matter to a peaceable conclusion.’ As you’d probably expect with Caesar he acted decisively and deceptively by pretending to separate from his troops so that he could enjoy a pleasant evening with his friends. He rejoined his men at the Rubicon River, the ancient dividing line between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy, this was traditionally the spot where a commander relinquished his commission and returned to Rome as a citizen. Any step across and an act of war would have been committed.

As he stared southwards into his homeland, Julius Caesar considered his options alongside his friends, according to Plutarch, as he contemplated the enormity of his actions he said: ‘My friends to leave this stream uncrossed will breed much trouble for me. To cross it-for all mankind.’ He also quoted his favourite Greek poet Menander, uttering ‘the die is cast.’ He led his army across the stream and into Italy.

Julius Caesar marched his men through the night until they reached Arimimum (modern Rimini) so that he could gain control of the passes in the Apennines. Despite choosing to commit to war rather than face prosecution, Caesar’s chances seemingly weren’t good, as most of his legions were still stationed in Gaul. But if the Senate harboured any sort of confidence, then it eroded fairly quickly. It seems that they misread the situation, thinking that Rome was dealing with a rebellious general; they expected Italian towns to send troops to defend the interests of the Senate. However, as in most societies the ordinary folk were extremely cynical about their political institutions, and when Caesar agreed to double the wages of his men, the deal was sealed, the Senate was helpless.

‘If I stamp my foot, all Italy will rise.’ Pompey pompously declared, but for of all of his bravado, he simply couldn’t back words up with action, and he had no choice but to flee as Caesar continued to march southwards. To be honest, I think both Pompey and the rest of the Senate were quite taken aback by Caesar’s actions, they had imposed their ultimatum, so to speak not through a desire to engage in war but merely to pressurise Caesar. The ploy had failed; Italian cities not willing to see any bloodshed simply threw open their gates and allowed the legions to pass through. Julius Caesar was now more or less ruler of Italy, he swept down towards Brundisium where he hoped to besiege Pompey and his army as they were preparing to board ship heading eastwards towards Greece. The hunt was on...