- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Ancient History

Julius Caesar: I Came, I Saw, I Conquered

The Man Chasing Pompey

Pompey Flees

On the 17th March, Pompey and his supporters set sail for the Balkans. Caesar, of course intended to pursue, but there were no ships available to him, so he had little alternative but to turn north and enter Rome. He broke into the treasury and appointed Lepidus as the prefect of the city and put Mark Antony in overall charge of the country.

In order to ensure that he wasn’t vulnerable in any sort of way, he hastily rode to Spain and led Roman forces stationed there back to Italy over the course of three months. Along the way, he scored a decisive victory at Ilerda in north-east Spain. Many of the soldiers captured had previously fought for Pompey, and understandably he did not try to force any to join his army against their will. He decided to restore property that had been confiscated from them, as a sign of goodwill. After capturing Massilia (Marseille) in a siege that lasted for six months he sent two of his legates to capture the island of Sardinia, in order to prevent Pompey from considering the possibility of blockading Italy.

The War Moves East

Into Greece

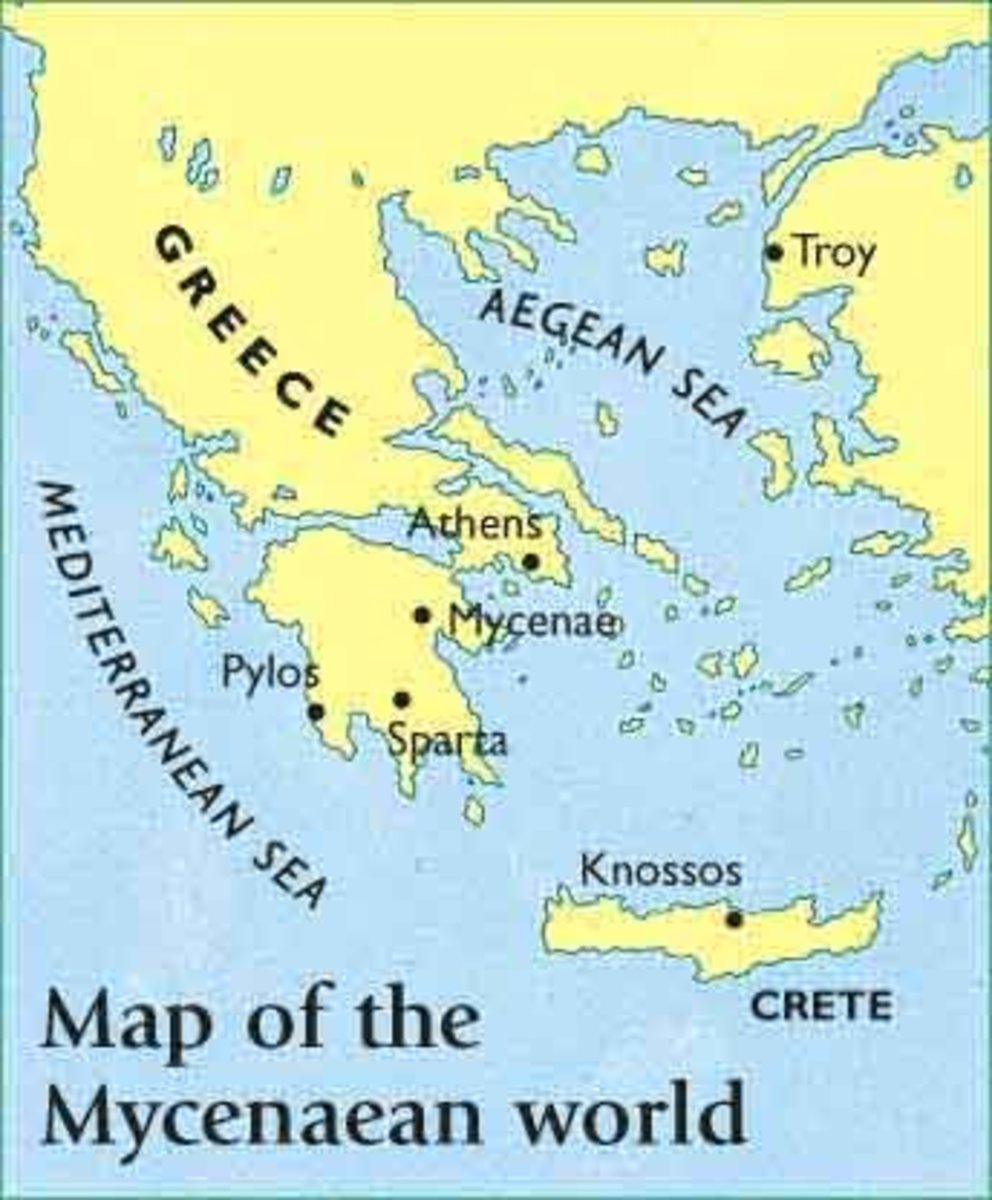

Julius Caesar took his legions back to Rome and spent ten days holding elections and quelling a riot that had broke out amongst his troops. Once all was back to order he set sail across the Adriatic in the middle of the winter, landing in modern Albania. He followed Pompey’s army doggedly, seeking to surround him at Dyrrhachium, after a rather daring march through a moonless night. Pompey foresaw Caesar’s strategy and easily broke through the attempted blockade, though strangely he failed to press home the advantage he had created for himself. Even Caesar himself commented: ‘Victory would today have gone to the enemy, if they had someone who knew how to win.’

The war now became a game of cat and mouse, with Pompey and his army marching hurriedly towards Thessaly in central Greece. Finally on the 9th August he halted his army on the plains of Pharsalus and made preparations to face his one time ally. Victory for Pompey really should have been a formality; he outnumbered Caesar by two to one. But statistics often do not account for skill and morale, the ensuing battle claimed 15,000 of Pompey’s soldiers compared to just 200 losses for Caesar. In the aftermath of the battle, Caesar trudged through the thousands of bodies and observed: ‘This is what they willed.’ In his mind, Pompey and his supporters were solely responsible for the carnage. The next day, the remnants of Pompey’s army, some 20,000 men surrendered to him. Once again, Caesar showed leniency towards those who had fought against him. True, he did execute some Senators, but crucially he spared both Marcus Brutus and Cassius, these men would re-enter Caesar’s life in the not too distant future.

The Queen that Melted Caesar's Heart

Zela

I Came, I Saw, I Conquered

Alexandria

Following his victory, Julius Caesar pursued Pompey to Alexandria, Egypt only to find out that his enemy had been murdered, probably at the orders of the boy king Ptolemy XIII. Ptolemy was engaged in a bitter struggle for the Egyptian throne with his sister, the famous Cleopatra. He hoped that by dispatching Caesar’s mortal enemy he could count on his support in the upcoming war. However, when presented with Pompey’s severed head and his signet ring, he wept. It could well be that the tears were genuine, but Ptolemy had done Caesar a favour, and the tears may have been to feign his delight at the death of his enemy.

Caesar only had two legions with him in Egypt, but nevertheless decided to intervene in the struggle for the throne, but not on the side you might think. At the same time, he met legendary Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII. In Egypt at that time, the concept of rule through a pure blood line was of paramount importance, meaning that it was Ptolemy and Cleopatra’s responsibility to produce an heir. It wasn’t exactly the wisest way of continuing the royal line for obvious reasons, but for the Egyptians it was important, both Ptolemy and Cleopatra were direct descendents of Ptolemy, Alexander the Greats famous general, and thus served as linking link to Alexander himself. Caesar’s first encounter with the queen came in her palace while being besieged by Ptolemy’s army. It’s said that Cleopatra gained entry into the palace by wrapping herself in a carpet. It’s not immediately clear what Caesar found so infatuating about her. Most accounts seem to suggest that she was hardly a ravishing beauty, but Plutarch helps shed a little light on the queen by suggesting that it was ‘her charm, the quality of her voice, the brilliance of her conversation and her stimulating personality,’ that helped to entice the Roman leader, despite the fact that he was old enough to be a father. Some historians claim that Caesar accidentally set fire to the famed Great Library, thereby destroying one of the seven ancient wonders of the world, and depriving the world of much ancient literature, though it seems more likely that the report was malicious gossip, stirred up by his enemies.

Finally, Caesar’s relief army arrived from Syria to lift the siege; a fierce battle followed which ended in victory for Caesar and Cleopatra, the death of Ptolemy and the capture of Alexandria. Caesar installed Cleopatra as queen to rule alongside her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV. The biographer Suetonius claims that Caesar took Cleopatra for a honeymoon cruise up the Nile, but this may well have been a voyage into the realms of fantasy.

In June 47 BC, Julius Caesar left Egypt for Syria to try and quell an uprising from none other than Mithridates son, Pharnaces II, the King of Pontus. Following the completion of a resounding victory at Zela on the 1st of August, he made the famous exclamation ‘veni, vidi, vici,’ or ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ Julius Caesar was now in complete control of the Mediterranean world. Meanwhile, back in Egypt Cleopatra gave birth to a boy named Ptolemy XV Caesar, who was given the nickname Caesarion (little Caesar). Having defeated his only true rival for power in Rome and calmed the storm that had threatened to erupt in Egypt and Syria. The new Roman dictator could return to his homeland to consolidate his power. However, his exploits in Africa and the Middle East had allowed his republican opponents to regroup. Caesar was dictator and master of Rome, but it was a position with shaky foundations, the Republic wouldn’t die without a fight.

The Republic's Last Stand

The Republic's Last Stand

The last Romans willing to fight to preserve a Republic that had stood for six centuries had gathered in North Africa and had successfully assembled a large army. Caesar had only spent three months back in the eternal city, when he was once again compelled to sail across the Mediterranean onto African soil, bringing with him six legions, all of them veterans of the Gallic and Civil war. However, he found it harder than expected to summon his supposedly loyal veterans to him, as many had been pensioned off a few months before, when they had returned to Rome. However, the problems were in retrospect minor for the dictator and he easily saw off the Republicans at Thapsus, in what is now Tunisia. The Republican commander, one Cato the Younger, an old foe of Caesar decided that it was best to take his own life rather than suffer the humiliation of being pardoned by the dictator.

With Tunisia now added to his burgeoning empire, Caesar annexed territories that had belonged to the Numidian King, Juba who had fought and died alongside the Republicans. At long last the civil war that had begun of the banks of the Rubicon, crossed over into Greece, and then North Africa were ended. In September, victory for Caesar was made official by the celebration of four triumphs to commemorate his victories over Vercingetorix, Ptolemy, Juba and the Republicans. However, the Republic wasn’t quite finished; in 45 BC Caesar was forced to suppress one final revolt in Spain, led by one of Pompey’s sons, obviously bitterly angry that the man that had defeated his father now controlled Rome. The battle of Munda on the 17th March, marked Julius Caesar’s last victory on the battlefield, again the key to his victory was experience, his legions were all battle hardened veterans that had fought against ‘savage and barbaric’ tribes.

My Personal Recommendations

Dictator

Julius Caesar finally returned home for good in October, and set about reforming and moulding the city into something approaching his own vision. Throughout his political career he had always been very good and garnering support from the mob, and as dictator he upheld his commitment to them by handing out free grain doles, and also offering Rome’s poorest a new life overseas in newly conquered lands. He ordered ancient cities that had been destroyed like Carthage and Corinth to be rebuilt and also built new towns, such as Arles in Gaul and Seville in Spain. In Asia Minor and Sicily he introduced a new taxation system, to protect the people from possible extortion and exploitation at the hands of local governors.

The veterans that had served Caesar so well for over a decade were finally demobbed in 45 BC, each man was paid an additional silver talent, roughly 21 kg which worked out as 26 years pay. However, the new Rome was beset with the problems of the old, namely huge debts that had climbed exponentially since the start of the Civil war, when interests had reached record highs. Radical reformers hoped that Caesar would wipe the slate totally clean and cancel all debts. But instead he decided that all debts outstanding had to be paid according to the valuations set before the start of the Civil war, minus interest or any amount that had already been paid. It was probably a move that Caesar had little choice to make; the alternative would have been the sufferance of another uprising.

The Senate House

Reshaping Rome

Julius Caesar was desperate to try and forge his own personal legacy upon the eternal city, and he wasted very little time. Firstly he commissioned the erection of the Forum of Caesar, a sort of ancient shopping centre set right in the heart of the city. At the old Forum, the political heart of the Roman world, he rebuilt the speaker’s platform, the court houses and the Senate building, now known as the ‘Curia Julia.’ Incidentally, while his grand new Senate house was under construction, he used the Theatre of Pompey outside of the city to hold Senatorial meetings under the watchful eye of his army. He also constructed a huge state library, to ensure that his spawning empire would become a beacon of education and enlightenment. As a mark of how much he valued the power of education, he bestowed privileges on all those that taught the liberal arts.

Julius Caesar wasn’t just a mad dictator; of course his lust for power and glory were obvious. But at the same time he was a well educated man, and was quite prepared to reform the Roman constitution, including proposing a law that discouraged extravagance, and offering protection and sanctuary to the Jews who had assisted him in his Egyptian campaign. He even planned to codify all of the existing civil laws. However, in that case there just wasn't enough time for him to execute all of these proposals. In fact, the civil laws would remain unmodified until the year 438 AD, when the Western Roman Empire was in decay and on the brink of destruction. The most remarkable thing that Caesar did was to reform the old Republican calendar, which consisted of 355 days and the addition of a random month to cover the deficiency. In order to implement the changes, Caesar sought advice from Cleopatra’s astronomer. The result was four extra months and a year that started on the 1st January. This marked the beginning of a calendar that we would recognise today, for the first time Rome followed the solar year, 365 days. So for anyone who loves a good New Year’s party, then Julius Caesar and his astronomer are the people to thank.

The old Republican government had consisted of around 600 Senators, magistrates, governors and their personal staff. With Rome’s recent expansion, came the need to enlarge the bureaucracy to cover new provinces and territories, and so he recruited an extra 300 Senators, he also selected more Praetors, more Aediles and more Quaestors. However, by far his most controversial policy was his rather loose approach at granting Roman citizenship. His uncle, many years before had granted citizenship to Italian allies that had assisted Rome, but Caesar went one stage further by bestowing Roman citizenship on the very same Gauls he had been fighting just a decade earlier, as citizens these people now enjoyed the same civil rights as any Roman and also received a small share in the benefits of the fledgling empire. Caesar even went so far as to start recruiting Senators from outside of Italy, a policy that didn't sit well with the aristocracy. To Caesar though, Rome wasn’t just about people, it was more of an idea or philosophy that he wished to spread to all the darkest corners of Europe. But for the people of Rome, and the old aristocracy the idea of living under the whim of one man was alien. Rome had not had an absolute ruler for over five hundred years, would the people, in particular the Senators who had spent most of their careers as Republicans stand for it?

More to follow: