The Old and Intriguing History of Maize

From the history of crops and other useful plants to man, there are two that I find quite interesting from several aspects. Both these plants are long known to mankind. They were both domesticated early during the development of the first civilizations, thousands of years ago, and their consumption remained localized for many centuries. The consumption of these plants is associated with two severe deadly diseases that remained mysterious for centuries. Curiously, their causes and subsequent cure have only been discovered at about the same time, in the twentieth century only! Both these diseases still manifest today and are mostly associated with poverty, like they were in the past. One of those diseases led to dramatic consequences in the recent history of a powerful country. While the other may have been the inspiration of very popular character that Hollywood loves, possibly the one with more movies made about it. Any idea of what that may be? I give you a clue; it acts mostly at night ...

The European Beginning

Maize, or corn like it is called in North America, Australia and New Zealand, is nowadays the most important crop in the world, judging from the amount produced annually. Together with rice and wheat they are the staples of over 4 billion people in the world. Thus, it is not surprising that maize along with the other two is the most studied modified and best known of all plant species. However, the history of maize although old, as maize is among the first plant species domesticated by man is rather peculiar. For centuries it has been restricted to its native land, Central America. The introduction of maize to Europeans was made by Christopher Columbus when he returned to Spain from his second voyage to the West Indies in 1493 bringing some strange yellow grains, from which Central Native Americans made flour and all sorts of dishes. At first, the European impressions were not great as they thought of maize as being more suited for feeding animals than people. Maize was then firstly used as a forage crop and very slowly gained importance in the European diet. Its importance as food in Europe derived not because it was very palatable to European tastes but because it started as being exempt from taxes and fees defined by the state and the church. Hence, the European consumption of maize started in Europe’s poorer classes and it remained that way until the twentieth century mostly. That is why there is very little literature about its use as food in its European beginnings; all due to prejudice ...

Thanks to its rapid adaptability, the cultivation of maize spread rapidly throughout the South of Europe. It started in Spain, from which the word maize comes from, and spread to Portugal in 1520. It was first cultivated in France in 1523, in Bayonne, introduced in Italy through Venice somewhere between 1530 and 1540 and then continued its voyage to Greece and the Balkan Peninsula during the late sixteen century. For this reason, maize was firstly known in Europe as the Spanish millet. With the population growth observed in Europe during the eighteen century, many farmers started to wonder about maize and its apparent miraculous yield when compared to the more traditional wheat and rice best known at the time. Due to the rising interest it did not take long for taxes and other fees to be introduced on the production and trade of maize, despite the protests of its poorest consumer and producer classes. The poor men profits have thus vanished into thin air. This led to disastrous consequences in Southern European societies, especially the less socially favoured. One of such consequences was the appearance of strange and very mysterious disease. In fact one of the most horrifying that was first medically described in Spain in 1735. Many names were given to it but its mystery was finally solved in the twentieth century only.

The Evil of the Rose

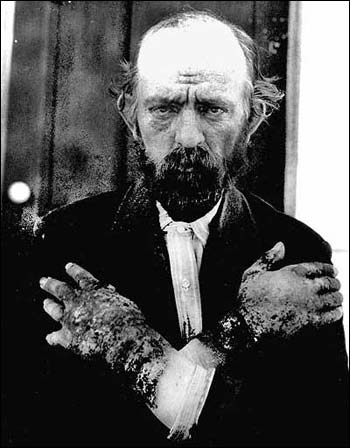

Unlike many other plants known at the time, especially those brought from the Americas, maize was the one that long kept its dark secret. On March 26 of 1735, a 40 year old man presented himself sick to Dr. Gaspar Casal, in Asturias, Northern Spain. According to Casal, the man had been suffering for some time. He complained about a strange fever that would often come and go, but without noticing any lack of appetite. However, he noticed that sometimes after eating we would go into a state of slumber without much memory of it other than it happened. According to the man, this would happen most frequently and severely in March. Also, he was not thirsty but often felt his legs loose up to the point of felling dizzy or vertigo; sometimes violently, especially when walking. He also had rapid mood swings and looked emaciated. He could not explain the continuous bitter taste in his mouth and his apparent intolerance to cold. His feet were always cold as ice but when he walked he felt like they were burning. His wife was also suffering from the same symptoms but unlike him there was one in particular that she could not bare. In fact, it was a complete torture for her, giving her infernal headaches from which she would try anything to avoid them. She could not stand heat or the sun, but unlike her husband she did not feel any cold, not even in winter. Both complained that every year at the beginning of spring, their hands and feet were covered with hard scabs that would later fall leaving noticeable scars.

Asturias and Galicia where Pellagra Was First Recorded

The 4 D's Disease

Not so long after more patients presented to Casal with the same symptoms. Casal started to follow and register the evolution of these symptoms together with many attempts and experiences in order to find a cure. He noticed the strange similarity of all cases and the disease strange appearance at the beginning of spring and disappearance in summer. Casal followed the first cases, reported by him, for three years noticing that the disease would appear in cycles with severely growing symptoms that would go from skin diseases to intestinal disorders up to a final stage in which patients would go into a horrifying madness that frequently led them to commit suicide, often by drowning in lakes, rivers or wells; as to put and end to such miserable and cruel living. The rest would simply dye in an impressive and terrifying state of morbid imbecility. After its first symptoms patients would dye within four to five years in cycles of severely growing symptoms. This disease was a complete mystery and intrigued doctors at the time and for almost 150 years after its first records. It seemed firstly confined to Asturias and Galicia regions, North-western Spain. Many names were given to it, popularly it was known as the evil of the rose, in Spanish mal de la rosa, due to the strange rose colour of the skin of those who suffered from it. Others, due its severity and resemblance with another infamous disease, simply called it the Asturian leprosy. The impact of this disease on the medical community was such that in fact it is recognized as the first modern pathological description of a syndrome. Due to its impressive symptoms, pellagra also came to be known as the four D’s disease: dermatitis, dementia, diarrhoea, and death.

An Epidemic has Started

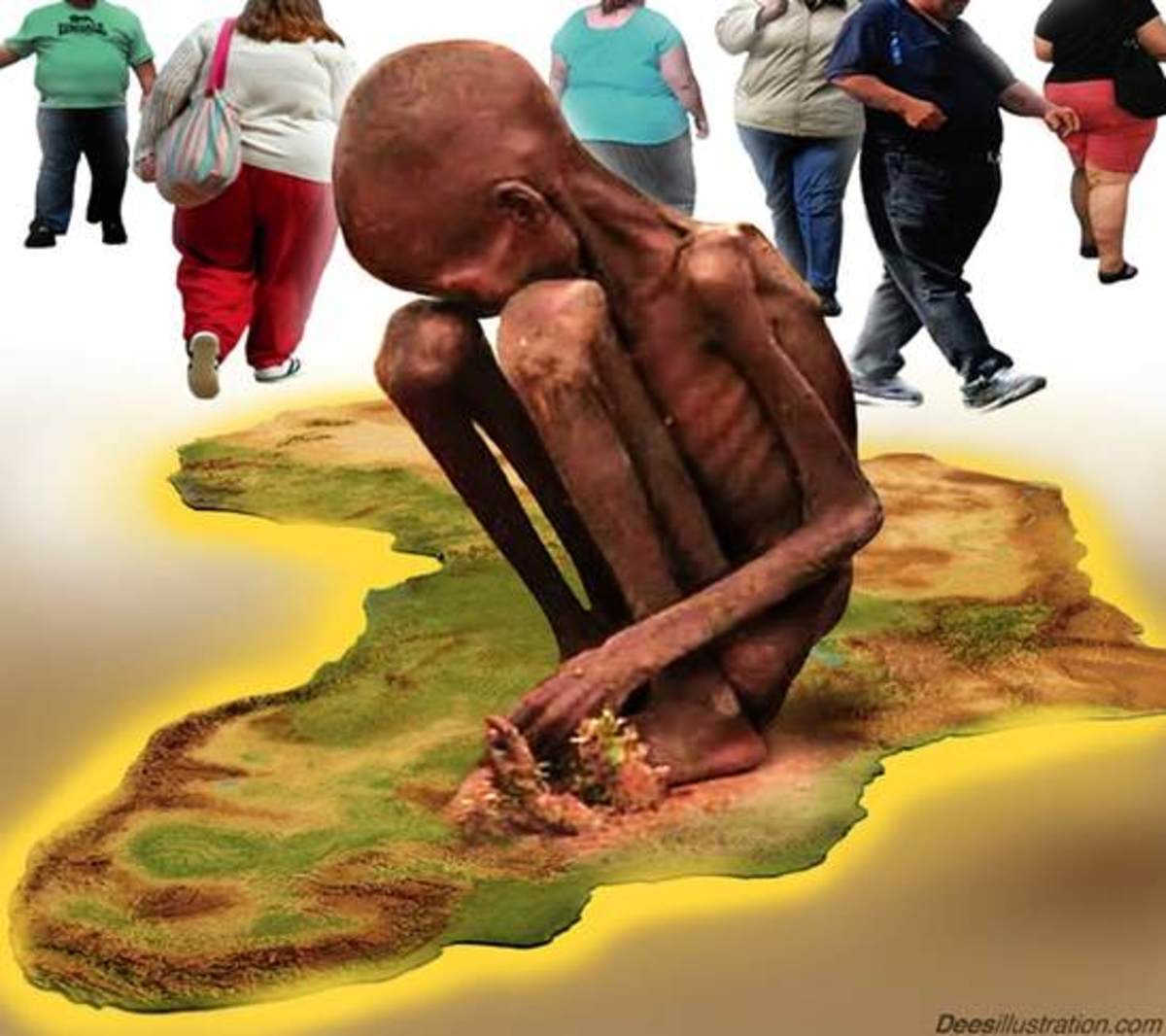

Years passed and the disease remained confined to poor rural areas of Northen Spain. No cure was available, treatments seemed to fail and the disease resembled more a divine punishment or some powerful curse destined to the poorest of the poorest. The first cases in Italy were first reported by doctors in 1771, in Milan. However, there were already rumours of strange and mysterious disease that affected poor peasants in the region of Venice where it was locally called pellagra, name by which it is still known today. On comparing notes and medical records it did not take long for doctors to conclude that half of Southern Europe was infected by it at the beginning of the nineteen century. However, it was only in 1842, more than a century after the first records by Casal, that French and Spanish authorities began to took measures as the disease was wiping out families, entire villages an communities, seriously affecting lower classes and especially labour and manpower needed for the industrial revolution that was also spreading throughout Europe. Because, pellagra was mostly observed in areas where maize was used as staple food, many suspected that maize had something to do with it. Either maize was toxic or it had the carrier of this mysterious and deadly disease. In France maize was banned as crop and its use was limited to very poor and isolated rural areas. Basically, pellagra became epidemic in the nineteen century Europe. In late nineteen century, pellagra also became epidemic in Southern USA and later on it was being reported from almost all over the world in communities where maize was used as staple food. I say almost and emphasise almost because the only region that seemed immune to pellagra was in fact its very origin where it all started in 1493; where maize was also and still being used as staple food. That is right, Central America! This puzzled the scientific community greatly and led scientists to investigate maize processing techniques in that region.

A Cure was Found 200 After Years Its First Reports

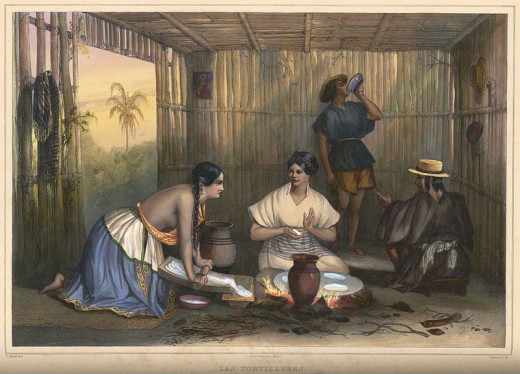

Many theories and causes where attributed to pellagra, from germs transmitted by flies that would seem more plausible to move around in poor people houses, to an apparent genetic inheritance again mostly suspected to be present in poor people. But what proved to be correct was nutrient deficiency. It was only in 1937, 200 years after its first reports, that the American biochemist and nutrition expert Conrad Elvehejm showed that pellagra was mainly caused by a vitamin deficiency, in this case niacin (vitamin B3) and tryptophan, an essential amino acid. What Columbus and the Europeans that followed him did not bring to Europe and to the rest of the world along with maize was the knowledge that Central Native Americans had on how to best prepare and use this apparent nutritious food that stopped many generations of Europeans from starving to death. Native people in Central America knew how to prepare this local crop safely. Traditionally, before they eat it, maize was treated with slaked lime or calcium hydroxide, a naturally occurring mineral. This procedure, called nixtamalization, has been discovered to date back at least 1200 to 1500 BC, long before Columbus, and it chemically liberates niacin present in maize grains. Today, the basic recipe for tortillas still includes the addition of lime. Yes, maize has niancin, vitamin B3. The thing is that our digestive system cannot naturally extract niacin from maize, even if deeply cooked, boiled or grilled. Also, compared to other foods maize is not rich in tryptophan. However, nixtamalisation was also found to increase the availability of lysine and tryptophan to some extent. But, more importantly, the indigenous Americans had also learned to balance their consumption of maize with beans and other protein sources such as amaranth and chia, as well as meat and fish, to acquire the complete range of amino acids needed for normal protein synthesis. Therefore, pellagra was unknown in Central America.

Central and Southern Mexico: Where All Began

The Consequences of Bad Politics

This balance or rather its absence is in fact what causes pellagra and to that end a set of unfortunate circumstances starting with wrong political decisions paved to way to the instalment of this dramatic disease. When maize started to be taxed in Europe as any other crop, the income of the poor families that relied on maize production was severely affected. This led them to restrain their diet as they were profiting less and less from producing and selling maize. Adding this shortage of income to a rapidly increasing population with limited resources even less alternatives, maize was still there easy and accessible to many up to the point of becoming the dominant food, comprising at least a third of the total ingested food in many regions. Adding this to illiteracy, ignorance, prejudice, social stratification, limited access to health care together with the limited scientific knowledge of the nineteen century, one can easily see why pellagra became epidemic and lasted for so long.

A Strange Inspiration

Now, about Hollywood and movies, what if I present you pellagra symptoms this way: emaciated appearance that would later develop into a morbid look; pale skin; gazed eyes; severe intolerance to sunlight or heat up to the point of creating blisters when exposed to sunlight with deep rose colouring of the skin as if it was burning; inability to eat normal food; insomnia; cold hands and feet; hair loss; edema; scars on the skin; aggression and horrifying mode swings that develop slowly into complete madness. Does this ring any bell to you? Well, Bram Stoker never answered this, but the main villain of his most famous novel – Dracula – and the vampire epidemic described in it may have been inspired by the strange news of a mysterious disease that was wiping out the poor and rural areas of Southern Europe at that time. This has been suggested several times by medical experts. If you red Stoker’s novel it is indeed an intriguing and funny coincidence between pellagra symptoms and the appearance and behaviour of the vampires described by Stokes.

Maize: The Wonder Plant

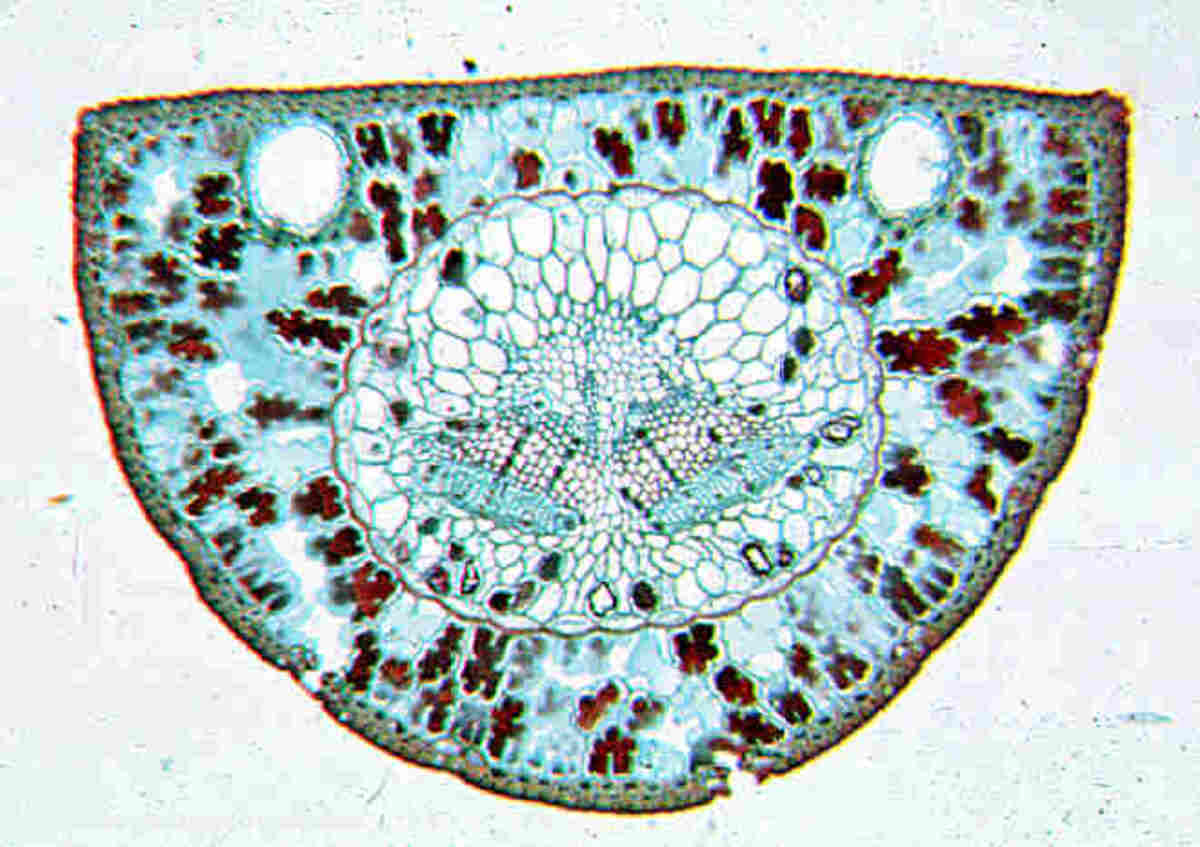

Last but not least, one final word about the plant that saved many from starving. Maize as we know it today, although with a scientific name to refer to it, Zea mays, is a very man-made plant species. Practically one can say that it has been made by design. Several theories have been proposed to point one ancestor wild species, possibly still existing. However, there is no wild species resembling maize not even remotely. Modern genetic sequencing showed that maize is descendent of teosinte, Zea sp., very possibly obtained through selective hybridization of its five wild species which may have started 7,500 to 12,000 years ago in Mexico. Maize and its wild relatives are very dissimilar. While maize can grow up to 10 t0 12 m tall, in some varieties, with large leaves and big ears, its wild relatives are small bushy plants with small ears with very few seeds. Apparently, these striking differences in size seem to be controlled by differences in two genes mainly. Maize is a biannual plant while two of its relatives are perennial plants. As a crop, maize is an extremely versatile plant. Although, grown mainly in wet and hot climates it has also been observed to thrive in cold, hot, dry or wet conditions.

About the other plant species and its dramatic history? Well, topic for another hub ...

Suggested reading:

- The Long and Troubled Voyage of Sugar: from the Idyl...

Sugar has long been known to man. However, sugar as we know it was only made around 400 AD and its industrialization occured much later in the sixteenth century. Here is a description of its long and troubled voyage from 8000 BC to our tables. Once c - Chocolate: The Aztec Treasure that Became Global

Once a treasure very well kept Aztecs, cacao made a long journey from its native Amazon forest to our cups and cakes. Used as currency in Central America, and served as beverage to Aztec royalty, it was then sweetened by Spaniards who created chocola - Vanilla: The Last of The Aztec Treasures

Once a very well kept secret, vanilla has become one the most expensive plant products today. It all started about 500 years ago with the arrival of Europeans to the coast of Mexico. - Plants and Portuguese Discoveries: How Americans Got...

Many of our most useful, tasteful and favourite food and plants have made a long journey to reach our tables at home. That journey began long ago and some of those plants changed European and Asian societies dramatically. Know more about how and why