Taking Memory For Granted: The Strange Case of Clive Wearing

Most of us secretly wish we had a better memory. Maybe we wish it so we can do better in school? Perhaps we have the desire to remember our children’s early years that have somehow faded unless they are connected to a picture or video. The fact that we have these wishes at all takes one thing for granted: we actually have a working brain that allows us to form, store, and retrieve our memories.

How often does the average person consider what it would be like to NOT have a properly working memory system? Sure we witness dementia or Alzheimer’s in older relatives and friends, but that is to be expected when the mind is towards the end of its journey. What would it be like if all of a sudden our memory system broke in the middle of our most productive years? What kind of Hell would that be?

How Memory Works

The most respected theory on how memory works was developed by two theorists in the late 1960’s named Atkinson and Shiffrin. Their theory was labeled the “three step processing model”. In other words, we process information in three steps: sensory memory, short term memory, and long term memory.

Sensory memory is the idea that our senses hold onto information for a very brief time before they pass it on to the brain. A simple illustration of this can be done by waiving your hand in front of your face. What do you see? Do you see a trail? I bet you did, but you aren’t on any drugs (at least I hope not), so why is that trail there? It’s simple; it’s your eyes holding the information in the sensory memory. You are seeing the past, right before it fades away.

I understand that view the past is a little mind blowing, but let’s move on to short-term memory. Short term memory is what’s in your head right now in this moment. Our short-term memory is not very good. We can only hold a handful of items in there until we start to get confused. An example of this is when you are told by a family member to stop at the grocery story on your way home. You take their call and give the affirmative that you will remember everything. Then you get home. Ouch, you forgot two or three things on the list. That’s the failure of your short-term memory. The general rule is that we can keep around seven items in there before we get confused. Furthermore, we need to rehearse and repeat those items to keep them there. Have you ever walked around reciting about seven things over and over again so you won’t forget? I bet you have. Short-term memory is terrible, but as you’ll see later in this article, essential to our lives.

To finish it off we have long-term memory, the place where permanent memories are stored. Are they all up there? Perhaps, but we need to be cued as to how to retrieve them. This is why a lot of things end up on the “tip of our tongue” and when someone finally gives you that important clue, you are able to remember things that otherwise you thought you forgot. When you finally remember you throw that information back into the short-term so you can spit it out.

So in summary: something in your surroundings hits your senses, if it is meaningful it’ll get passed to your short-term memory, and if, but only if, you rehearse it enough, will it get stored in your long-term memory for later retrieval.

You may enjoy these other Psychology related links:

- Learning How To Study Effectively

Knowing how to study effectively is a key part of our educational experience. Unfortunately for many of us, no one ever “taught” us how to study and, in turn, we have missed opportunities to do better in school. Luckily, there are many tricks that ca - Examples of The Bystander Effect

The Bystander Effect is a tragic, yet real, part of the human experience. Why do we not help others when they may or may not be in trouble? Video examples of this very interesting psychological concept are provided.

Memory and The Brain

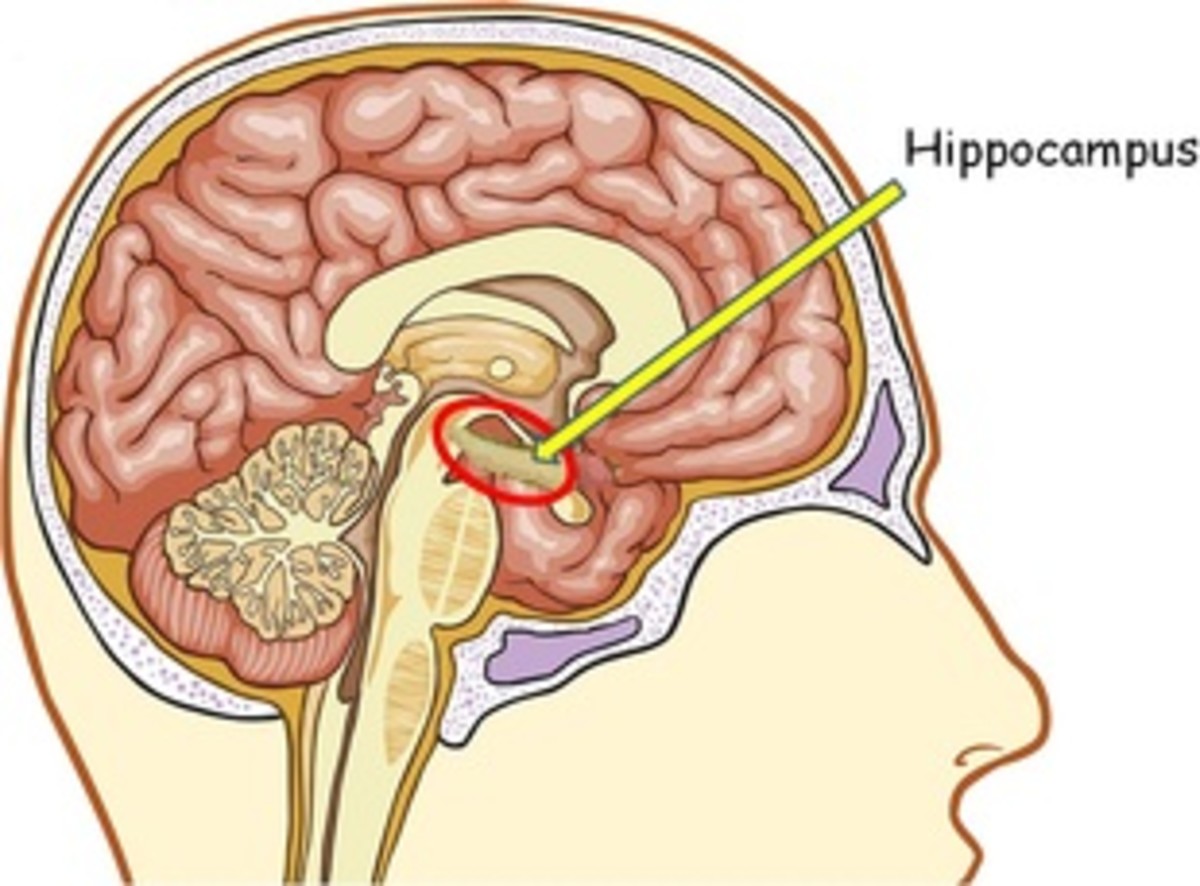

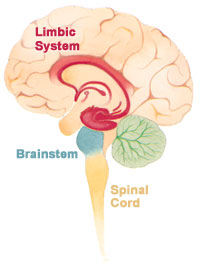

How memory works in the brain and body is very much a mystery. There are many brain parts in play when we go through the memory process. The front part of our brain, very unoriginally named the Frontal Lobe , helps us organize our memories. Also, the adrenal gland and stress hormones most certainly play a role (have you ever notice that you tend to remember trauma better than most other things in your life). Clearly these body mechanisms are all working at the same time, so we can’t pinpoint one specific brain part that deals with memory. And then, there’s the Hippocampus.

The Hippocampus is deep in the center of our brain and in the rare cases when it is damaged, humans and animals can no longer form “new” memories. Essentially, they lose their short-term memory which, in turn, impacts their ability to ever put new information into their long-term memory. In a laboratory setting this is easy to do with a rat or mouse, but for humans, something extraordinary has to happen in order to harm this brain part. For one man, Clive Wearing, this became an unfortunate reality.

Clive Wearing

In the 2000 film Memento (directed by Christopher Nolan of Batman and Inception fame), a young man tries to solve the mystery of his wife’s death without the ability to form new memories. He therefore ends up creating vast amounts of notes, including tattooing his own body, to try to remember the evidence. Although it is brilliantly directed and one of my favorite movies of all time, the film is extremely unrealistic when it comes to portraying the main character’s ability to use his memory. Clive Wearing shows us what Hippocampus damage is really like.

Clive was a world-renowned classical musician when he came down with a headache in the spring of 1985. That headache turned out to be Viral Encephalitis which caused a swelling of his brain and the complete destruction of his Hippocampus. From that day forth, he can no longer form any new memories. No memory of a person entering a room. No memory of how a conversation started. No memory of how you got where you are.

So next time you are frustrated about not remembering something you wish you could, or you get a question wrong on that next test, put it in perspective and thank whatever you believe in that you have a memory system at all.