The Admirable and Forget-me-not Nepenthes Plants

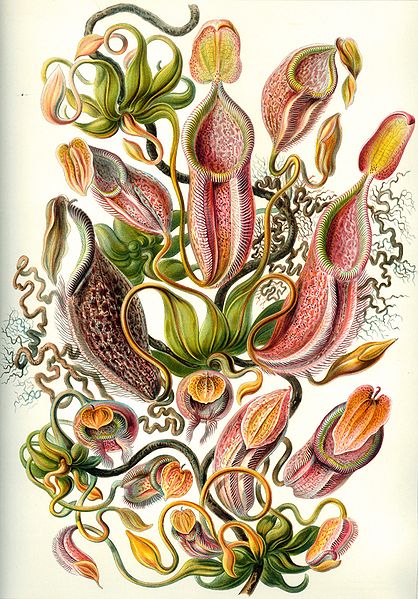

While is true that plants serve as food for many animal species, there are exceptions in which the roles are reversed – plants feed on some animals, mostly insects. In very adverse environments with soils depleted of most mineral nutrients that plants need to grow – bogs, wetlands, mountain slopes swept by heavy rain – plants found ways of getting those nutrients, the most important nitrogen, from animal life. For that they have adapted their leaves to capture, trap and process their animal preys. One of the more sophisticated adaptations of their leaves is shown by the tropical pitcher plants or nepenthes as they are also known. There are about 130 different species of flowering climbing vines all belonging to the same genus Nepenthes and to the same family Nepenthaceae; which is thus called monotypic, of one biological type only. They are mainly located in the tropical Southeast Asia, but there are also species in India, Madagascar, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, New Caledonia and North Australia. In these regions they can be found in highlands and in lowlands, hence being submitted to different conditions of light, humidity and temperature.

Leaf Development and Pitcher Diversity

Leaf and trap development is similar in all nepenthes species. The trap development process begins when a tendril forms on the tip of a leaf and begins to extend. It grows fast and attaches eventually to winning support by wrapping itself on another neighbouring plant, usually by a single lap. The tip of the tendril begins to swell and falls by its own weight. Then, suddenly swells with air increasing its volume. As this leaf tip increases, like a balloon, in most species coloured spots begin to appear on its walls. The trap is then filled with liquid, more than half its volume in some cases. When growth is complete, a segment similar to an operculum appears at the top that is firstly closed by a lid that soon opens. Once the lid opens the trap is ready to receive visitors. The shape of these leaf modifications, traps, as their colour and other morphological features like hairs and appendages vary greatly within nepenthes species. The fact that these species are very similar in nature and closely located, in most cases, makes them possible to hybridize naturally, which further increases their variety and also makes their classification based on morphological features more difficult.

Apart from their unique appearance this fact also contributed to their high popularity as ornamental plants, as many man-made hybrids became available and widespread cultivated, thus increasing further their colourful and magnificent variety. Trap shape goes from beakers and jars, narrow neck bottles, glasses for champagne, tall and slender tubes and even some look like small flush toilets. Some are hung like lamps, along the branches of the tree that supports the nepenthes plant; some nepenthes species are epiphytes, i. e. they live on top of other bigger plants, like trees. Other pitchers, from lower plant parts, just simply sit on the ground. Mature nepenthes plants often produce traps that are different in shape and size whether they are located at the lower parts of the plant or higher closer to younger plant parts. Usually, upper traps are smaller. The biggest of all nepenthes traps is made by Nepenthes rajah, usually found sitting on the ground. Their huge bulging tanks can easily hold about 2 l of digestive liquid. Reportedly, some contain 4 l. The traps of Nepenthes rajah are so big that small mammals like rats have been found drowned in their traps. Whether Nepenthes rajah is capable or not of digesting the rat remains that is disputed. Frogs, small lizards and birds have also been found in some bigger nepenthes traps. However, these are most probably exceptions and result from accidents suffered by sick animals which are thus far from being the norm. These traps evolved for digesting insects and invertebrates mostly.

Attracting Insects

The strategy for capturing and digesting insects is the same as found in other carnivorous plants, i.e. Sarracenia, the North American pitcher plants. The nepenthes attract insects with the scented nectar secreted by its traps. In some species one can easily see the exudate accumulating on the inner surface of the lid, strategically placed faced the trap entrance, lined by the peristome. Thus, from all the visitors that come to feast on the irresistible nectar some of them might eventually slip through the walls or even fall down the directly into the trap. For many insects, the nectar has an intoxicating effect. After feeding for a while, some insects can appear to be in a drunken stupor, walking or spinning in circles. Many of these lose their foothold, falling from the lid or peristome into the depths of the trap. The treacherous nature of the inner surface of the trap walls further complicates any attempt of escaping by climbing back due to their waxy and scaly texture that makes insects to lose their balance upon climbing it. Once the lured insects into the water solution at the bottom they begin to struggle to save themselves instinctively. This liquid is often thick and almost syrupy, so that prey sink quickly and drown. The water movement caused by prey stimulates the digestive glands in the walls inside as they begin to release digestive enzymes, acid in nature as low as pH 3. These substances are so powerful that a fly is reduced to an empty shell in days and a mosquito disappears completely within a few hours. The entire device is so effective that nepenthes can catch and digest from small insects, cockroaches, spiders, centipedes and larger scorpions that are attracted by other insects that came for the nectar.

The Other Side: More Than Just Feeding on Insects

Apart form their “carnivorous” habits nepenthes are not always the villain of the story. These plants are also landlords, they have tenants, which are thus called nepenthes infauna or nepenthephile. Some of them are found inside the pitchers of specific nepenthes species only. The larvae of several insect species have become immune to the digestive fluids of nepenthes and feed on detritus, from plant or animal sources, which accumulate at the bottom of the trap. Other larvae remain hanging at the top, coming down occasionally to get one of these animals that feed on detritus. There is also a terrestrial crab, Geosesarma malayanum, that frequently visits nepenthes, mostly Nepenthes ampullaria, in Malaysia, competing for the drowned preys of nepenthes. However, it has been reported occasionally that these crabs end up by being drowned in the traps. The nepenthes seem to take a few benefits of this small number of so privileged tenants. Like all animals, when they breathe, they release carbon dioxide that can then be absorbed by the plant. Remember that, although highly modified the trap is still a leaf and as all plant leaves it also photosynthesises to produce food that is then distributed to all of the plant body. The excrements of the tenants, rich in nitrogen, sink at the bottom and are also a valuable food for the plant. Some tenants may also chew the remains of the corpses that the plant finds indigestible, thus preventing the deposit and decomposition at the bottom of large fragments, which would lead to rotting of the plant wall. These symbiotic relations sometimes develop into really intimate plant-animal relations.

Nepenthes bicalcarata, also known as the fanged pitcher plant, has made special reserves for these unusual companions. The name fanged comes from their pair of large nectaries hanging from the trap lid that resemble a pair of vampire or snake fangs. The tendrils of the Nepenthes bicalcarata trap are hollow and are thus used as a house by Camponotus schmitzi to make their nest; a species of carpenter ants, which are thus called because they built nests on wood or plant material although do not feed on them like termites. These unusual ants often dip into the liquid in search of dead insects and carry them back to their nest. The ants are more beneficial than harmful to the plant. They take some parts for their own consumption, but the others fall back to the liquid, being more easily digested by the plant in its fragmented form. Also, the task performed by the ants is really herculean. In other occasions, the ants may also prey on live visitors thus competing with the landlord. It has also been observed that these ants protect Nepenthes bicalcarata against a common beetle that is known to feed on these plants and cause serious damage. In order to benefit form the ants and allow them to live in its trap, Nepenthes bicalcarata digestive fluids are less acid than what is normally found in other nepenthes species. This fact may explain why tree frog eggs and consequent tadpoles have been found inside Nepenthes bicalcarata traps. In addition, Camponotus schmitzi ants are found nowhere else except living in the Nepenthes bicalcarata pitchers, they are totally dependent on the plant for food and housing. On the other hand, Nepenthes bicalcarata can survive without the ants. This is one more example of a close symbiotic relationship between ants and plants, in which Nepenthes bicalcarata is called a myrmecophyte – a plant that hat lives in a mutualistic association with a colony of ants. Nepenthes ampullaria has probably the largest tenant, a regular mite of about 1.25 cm long, with red claws and belly and the back mottled with black and green. So far, no more than one was ever found in a single plant, and their relationship remains somehow mysterious as scientists do not know yet what the mite gets from that plant and what it gives in return. As you can easily see preserving nepenthes in the wild is crucial not only for the right of living as beautiful and extraordinary plants that they are but also for the inumerous benefits that they offer to the community surrounding them and for the wonderful micro-worlds that they manage to keep.

A funny video about Nepenthes bicalcarata and its tiny allies

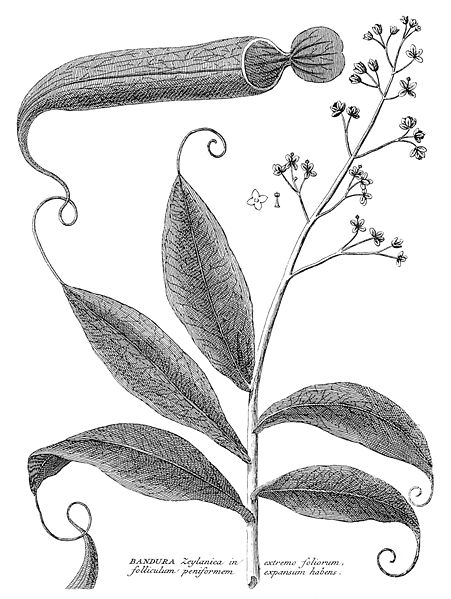

Their Beauty Has Long Been Known

Finally, and to end this long and most pleasant writing hub, one final word about the curious scientific name nepenthes. These plants were first described in 1658 by the then French governor of Madagascar, Etienne de Flacourt. He described the species Nepenthes madagascariensis in a book on the history of the island, a strange plant with "a hollow flower or fruit resembling a small vase, with its own lid, a wonderful sight." The second species described was Nepenthes distillatoria from Sri Lanka. They soon amazed scientists and their origin and the function of its traps was not always met with consensus. They were given many names. The name Nepenthes was first coined in 1737 by the famous Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus, in his work Hortus Cliffortianus. When Linnaeus saw the first dried specimens of nepenthes he was euphoric. Nepenthe,a Greekword, literally means without grief (ne = not, penthos = grief). In Greek mythology nepenthe is a drug that quells all sorrows with forgetfulness. Linnaeus recalled Homer's The Odyssey, and the drug Nepenthe that Helen of Troy threw into flasks of wine to alleviate soldiers' sorrow and grief. Linnaeus wrote, "If this is not Helen's Nepenthes, it certainly will be for all botanists. What botanist would not be filled with admiration if, after a long journey, he should find this wonderful plant. In his astonishment past ills would be forgotten when beholding this admirable work of the creator!” The irony is that in fact nepenthes has an intoxicating effect on their prey. Sir Joseph Hooker, friend of Darwin, proved the carnivorous nature of nepenthes and wrote the second monograph on the genus listing thirty-three species in 1873.

More about symbiotic relations between ants and plants:

- The Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, and Its Fearless Alies

Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, native of Central America is best known for its symbiotic relationship with a species of ant that lives in it the hollowed-out tree thorns. The ants are famous for defending the tree fearlessly against ravaging in - The Aerial Life of the Ant Plants Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia

This group of plants, the ant plants, from the genera Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia, found an efficient way of living and surviving under adverse conditions. The reason for that success lies on the unusual relation that these plants established with the

More about Plant-Animal Intercations:

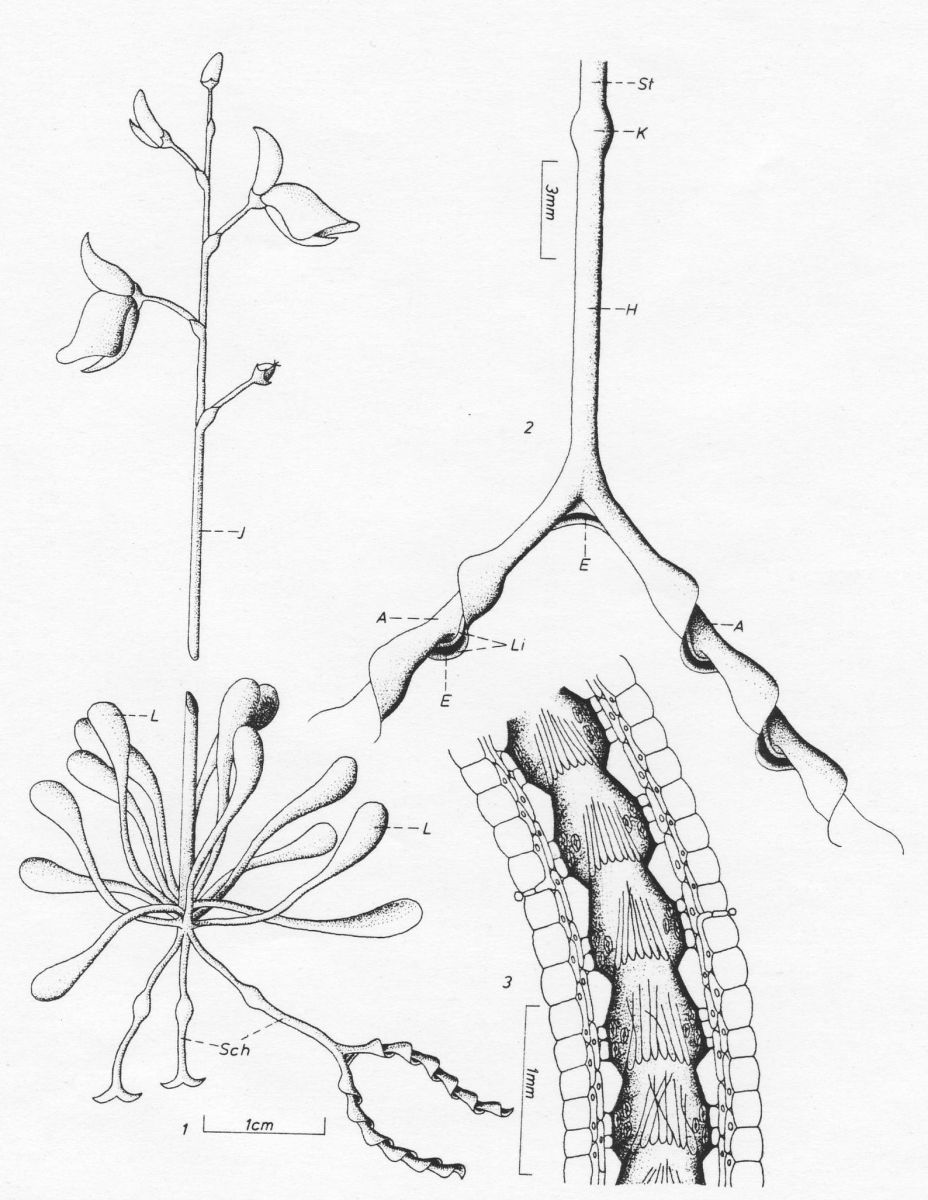

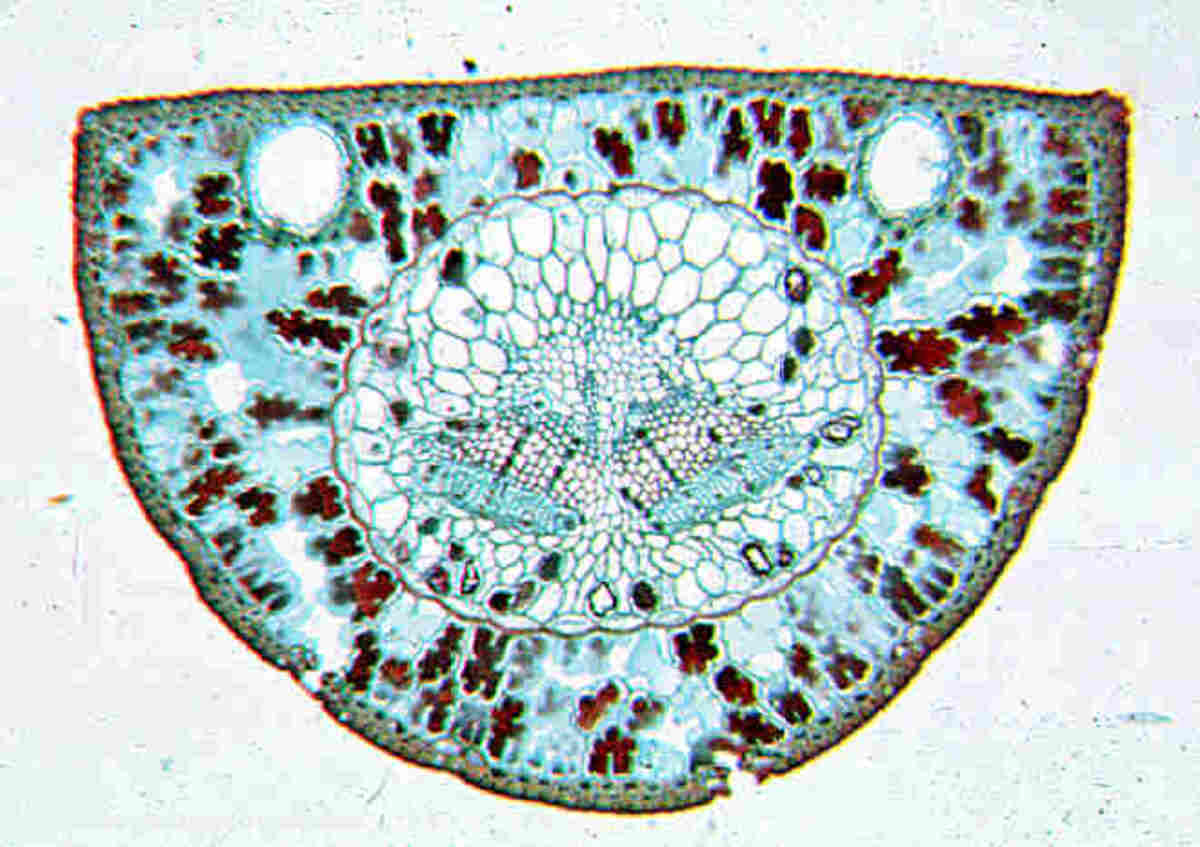

- The Covert Affairs of Genlisea: A Master of Deceptio...

It took about 100 years to prove Darwin's predictions about the carnivorus nature of Genlisea genus. Today they have become popular pet plants among the carnivorous plants fans who called them corkscrew plants. Know more about its elusive and mysteri - Orchids: A History of Sex, Drugs & Lies

Orchids are probably the most popular flowering plant species. They are also the most evolved from all plants. They managed to spread successfully across the world by developing the most complicated relationships with its pollinators. Some of them ha - The Irresistible Powers of the Corpse plant, Helicodiceros muscivorus

In Mediterranean islands of Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic islands grows the corpse plant, Helicodiceros muscivorus. If found an unusual yet efficient and smelly way of sucessivly atract blowflies as its main polinators. - The Aerial Life of the Ant Plants Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia

This group of plants, the ant plants, from the genera Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia, found an efficient way of living and surviving under adverse conditions. The reason for that success lies on the unusual relation that these plants established with the - The Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, and Its Fearless Alies

Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, native of Central America is best known for its symbiotic relationship with a species of ant that lives in it the hollowed-out tree thorns. The ants are famous for defending the tree fearlessly against ravaging in - The Sweet and Deadly Trap of the Portuguese sundew, Drosophyllum lusitanicum

In the southwestern Europe lives the Portuguese sundew or dewy pine, Drosophyllum lusitanicum. It is shrub-like carnivorous plant endemic of Portugal, southern Spain and northern Morocco. It is unique in its genus and lives under the most strange con