The 'Mendi' Disaster by Murray McGregor

A rationale for this Hub

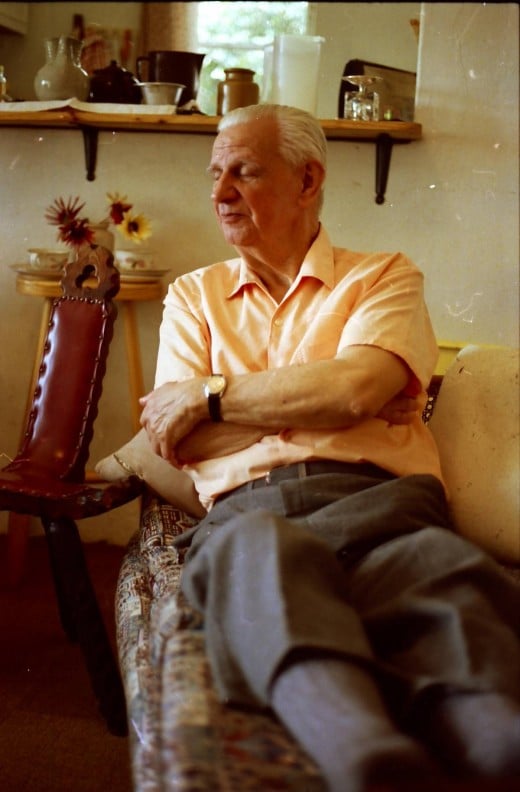

My late father Murray McGregor wrote the following account of the incident which has gone down in South Africa's history as possibly its greatest military and maritime tragedy, the sinking of the troopship 'Mendi' off the coast of the Isle of Wight in February 1917. Unfortunately my father was not in the habit of dating his writings so I can only conjecture that he wrote this sometime in the early 1980s. I recently found it among his papers.

I share this with my fellow-Hubbers as I think it is interesting as a part of our shared history of the two world wars which so shaped the world in the 20th Century. No doubt none of us has escaped some influence from those wars. In so many ways they are still, perhaps not in any way acknowledged, but still there.

Culturally, socially, politically and economically those two wars are still in our minds. This story is just one of many which have been told, and no doubt still will be told in the years ahead.

I also share it as there is still a lot of South African history which my fellow-citizens still have to come to terms with, and perhaps there are lessons for us in this amazing story.

The other reason is that the anniversary of this great tragedy is coming up soon and I would like people to spare a thought for the men who died so far from home.

I also share it as another perspective on the Hub which I wrote last year (before I found my father's article): “Troopship Mendi: death at sea on a cold, foggy morning”

My father's text follows with no editing or embellishments (apart from the pictures) from me:

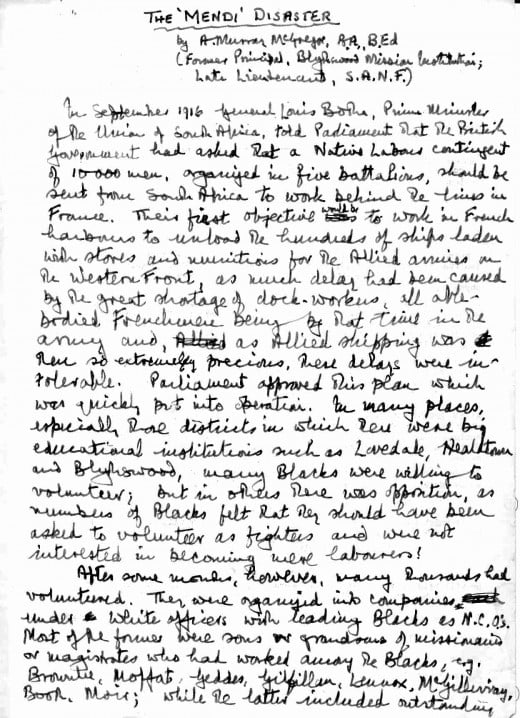

The 'Mendi' Disaster

by A. Murray McGregor, B.A., B.Ed.

(Former Principal, Blythswood Mission Institution; Late Lieutenant, SANF)

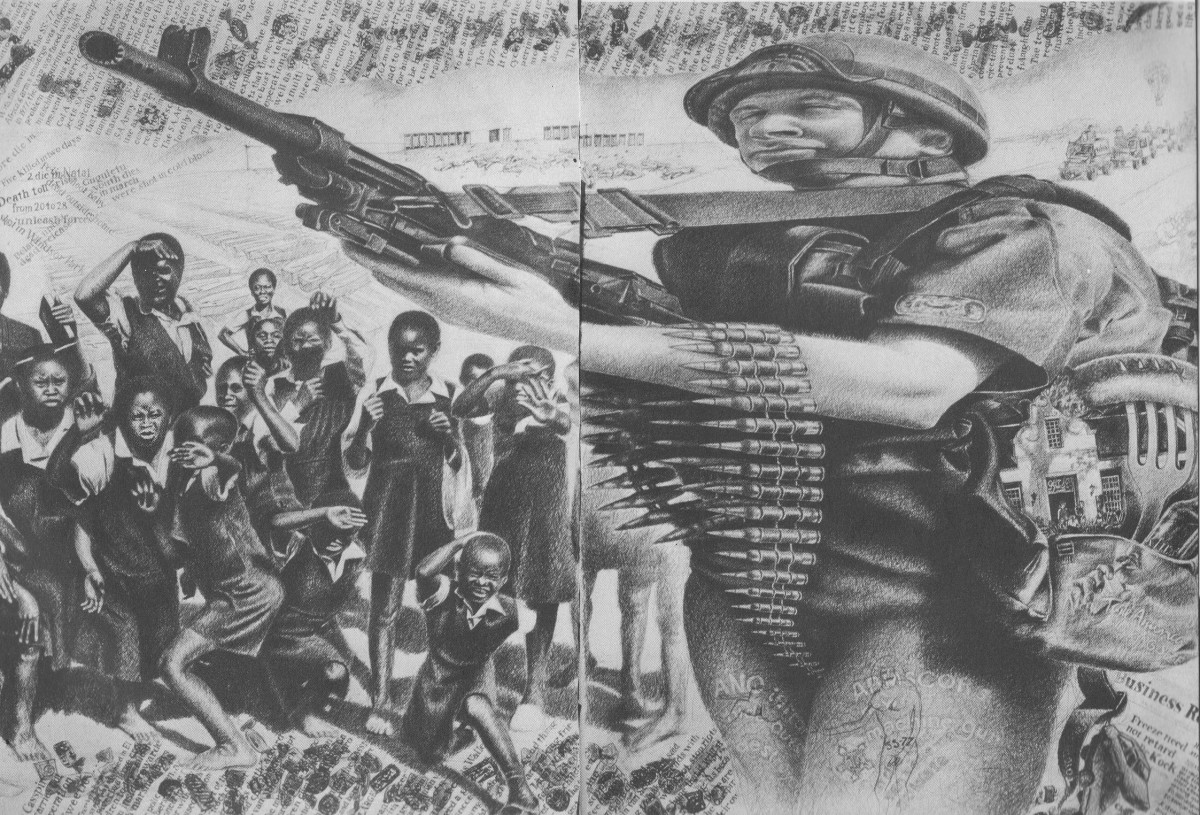

In September 1916 General Louis Botha, Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, told Parliament that the British Government had asked that a Native Labour contingent of 10000 men, organised in five battalions, should be sent from South Africa to work behind the lines in France. Their first objective would be to work in French harbours to unload the hundreds of ships laden with stores and munitions for the Allied armies on the Western Front, as much delay had been caused by the great shortage of dock-workers, all able-bodied Frenchmen being by that time in the army and, as Allied shipping was then so extremely precious, these delays were intolerable. Parliament approved this plan which was quickly put into operation. In many places, especially those districts in which there were big educational institutions such as Lovedale, Healdtown and Blythswood, many Blacks were willing to volunteer; but in others there was opposition, as numbers of Blacks felt that they should have been asmed to volunteer as fighters and were not interested in becoming mere labourers!

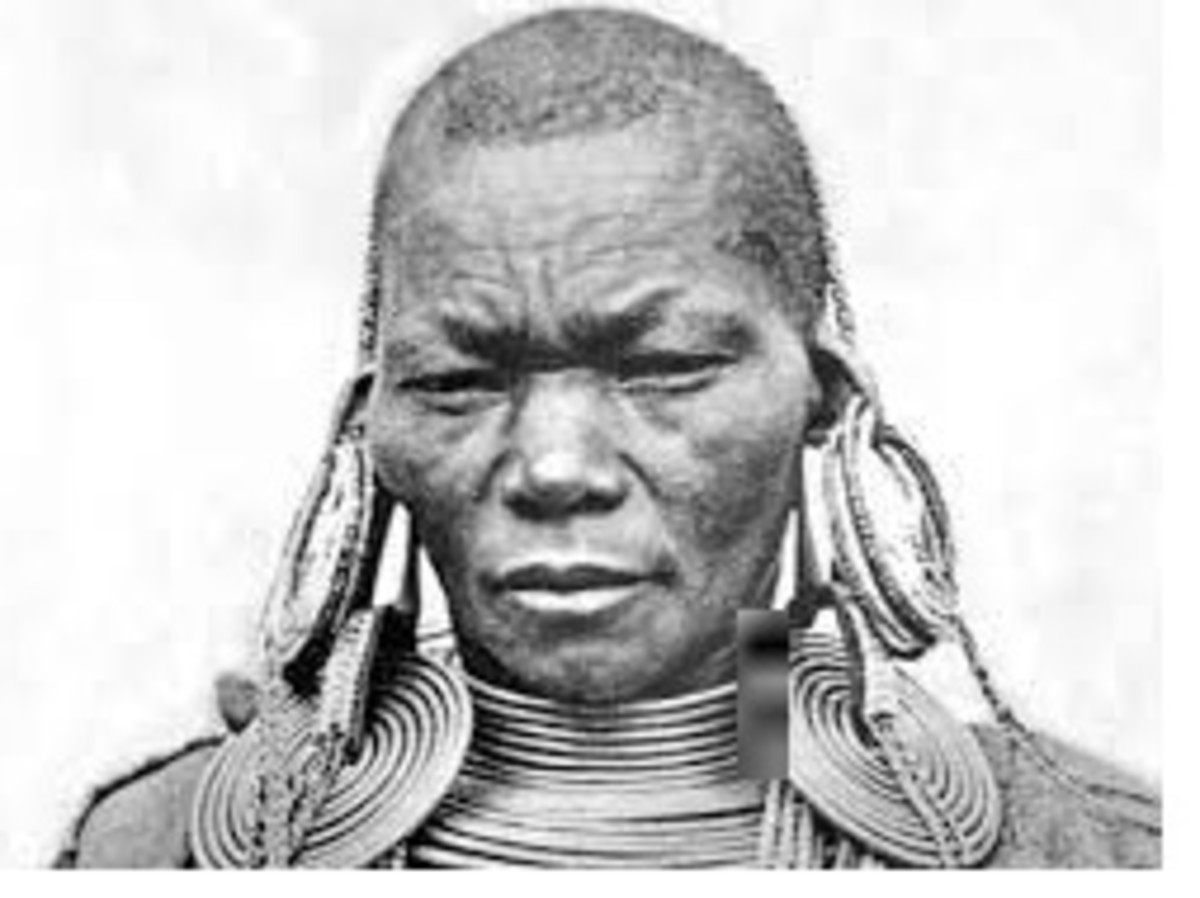

After some months, however, many thousands had volunteered. They were organised into companies under white officers with leading Blacks as NCOs. Most of the former were sons or grandsons of missionaries of magistrates who had worked among the Blacks, e.g. Brownlee, Moffat, Geddes, Gilfillan, Lennox, McGillivray, Booth, Moir; while the latter included outstanding Blacks who were sons or grandsons of well-known chiefs, e.g. Dalindyebo, Moroka, Moshoeshoe. There were also Black chaplains to work among the volunteers. These men were sent to Europe as fast as transports could be provided for them; and those who arrived safely did fine work in the seaports of France and behind the lines.

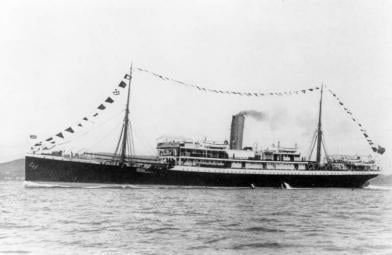

But not all of them reached their destinations. On 6th January 1917 a transport, the 'Mendi', of 4230 tons, formerly a mail steamer of the Elder-Dempster Line running between Liverpool and West African ports, left Cape Town in convoy with five other ships (including the well-known Cape Mailship Kenilworth Castle) escorted by the old 'County' class cruiser 'Corwall', reaching England some three weeks later. Then the 'Mendi' proceeded from Plymouth independently to France on the night of 20 February 1917, across the Channel to Le Havre. As it was wartime she sailed without lights.

It was rough and stormy in the Channel and visibility was poor. At 5 a.m. On the 21st, when it was still dark,. Another ship, the 11000 ton steamer 'Darro', a passenger-vessel bvelonging to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, on passage from Le Havre to Liverpool, also steaming 'blacked-out', ran into the unfortunate 'Mendi', smashing a huge rent in her starboard side. The smaller ship immediately started filling with water and heeled over to starboard. So quickly did she heel over and start sinking that it proved impossible to launch many of the lifeboats or life-rafts. Within 20 minutes she had disappeared. Many of the men of the Native Labour Corps had been crushed to death in the impact, many more were drowned by the icy water that poured into the ship, the rest left to struggle and most of them to drown in the wild, dark waves. Of the 894 men that had been aboard the 'Mendi' only 261 were rescued, the majority men of the NLC.

The white survivors spoke with admiration of the wonderful behaviour of the Blacks. There was no panic at all and many heroic deeds were done as they tried to save and encourage each other. One small group formed themselves into a circle round their NCO and, exhorted by him, did a war-dance until overwhelmed by the waves. So greatly did their behaviour impress the crew of the 'Mendi' that several of them gave up their places in the few lifeboats that could be launched to men of the Black Labour Corps.

Among those who perished in this disaster was one of the chaplains, the Rev. Isaac Wauchope, one of the Black former students of Lovedale. He was one of the four evangelists taken by the Rev. James Stewart of Lovedale in 1876 to start the Livingstonia Mission in Nyasaland (now Malawi). He was one of those whose faith and courage had been of such great help to his comrades at and after the collision.

This was South Africa's biggest maritime disaster in the 1914-1918 War. When the news reached the Cape, Parliament was in session. General Botha received the dispatch in the House and immediately rose to interrupt its business. He read the tragic news, mentioning that 10 white and 615 Black members of the NLC had lost their lives, adding that the Imperial Government would pay compensation to the relatives of the dead. He then moved a motion of profound sorrow and the sympathy of the House with the relatives and friends of those who had perished 'in loyla service to King and Country,' adding an eloquent tribute to the loyalty and good behaviour of all South African Blacks during the War. Leaders of all parties added their tributes, and the session then ended with all the members standing with bowed heads in honour of those who had died.

We have all heard of the African bush telegraph; it is a fact that the news of the disaster of the 'Mendi' was known in the Transkei before the official announcement about it was issued in Cape Town.

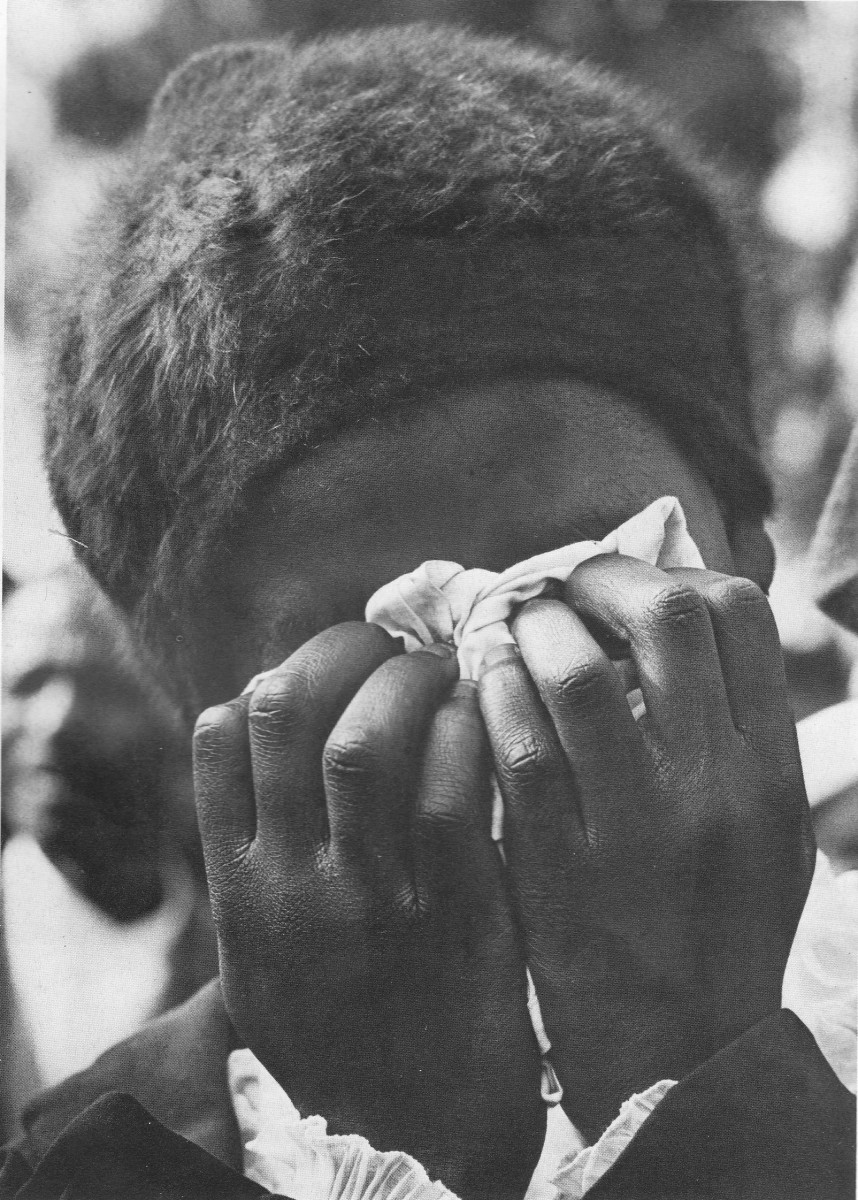

As so often happens, the sorrow of the Black people was given expression in a most beautiful song of mourning which is still well-known and loved by Blacks, especially in Ciskei and Transkei. To hear a black male choir singing 'Mourn for the Mendi' is an experience not easily forgotten.

Sources:

Shepherd: Lovedale 1841 to 1941 (Lovedale, 1942)

Murray: Ships and South Africa (OUP, 1933)

Smith: Passenger Ships (Den, Boston, 1963)

Also various numbers of The Blythswood Review, 1924 – 1931.

Final comments by me:

The comment about the people in remote areas of the country knowing about the disaster before the official announcement was made is not corroborated, as far as I know. It was mentioned in Eric Rosenthal's African Switzerland (Cape Town, 1948) but, as the writer of Black Valour, Norman Clothier (University of Natal Press, 1987) has written: “:This writer is not always reliable.”

Also the possibility of the men doing a “war dance” on the deck of a ship with a heavy list to starboard is also not likely and was in fact not testified to by any survivors in the intensive investigations that followed the disaster. The story first made its appearance in print in J.S.M Simpson's South African Fights (London, 1941). However it is a story which stirs the emotions of all who hear it, as does the alleged call of the Rev. Isaac Wauchope Dyobha to the men to “Be quiet and calm, my countrymen.”

- Troopship Mendi: death at sea on a cold, foggy morning

On a cold, foggy morning in February 1917 more than 600 members of the South African Native Labour Contingent died as a result of the collision of their troopship, the SS Mendi, with another ship. - Leaves from My Logbook

This site contains the text of the memoirs of my late father Murray McGregor, who was born in Worcester, Cape Province, on 26 May 1908, when the Province was still a colony of Great Britain. He died in 2002, having lived through two World Wars, t

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2010