The Nature of Change, Finale

Perpetual Change

One of the most striking things about the phenomenology of development is its generality. It is, in fact, a phenomenology that describes the emergence of everything, including the universe as a whole and its laws of causality. The universe is quite mature now, and its laws of physics appear to be inviolable. But cosmologists have discovered that there was likely a time early in the universe’s development when these laws did not exist—they had not yet developed. That immature universe had many degrees of freedom that were eliminated as it matured into its present state. Thus, the predictable causality manifested by determinative laws of nature (e.g., gravity) is nothing more than information created by a developmental reduction of indeterminacy in the early universe.

In essence, causality is like an addiction. If the universe as a whole were conscious and motivated, perhaps it could overcome this addiction, and change the laws that govern the behavior of its inhabitants. Until then, we puny inhabitants are stuck with those laws.

Many probably object to my likening the laws of nature to an ‘addiction’. And perhaps that word is too highly specified, with too much baggage to be a fair descriptor. ‘Habit’ is probably a better word. That is, the laws of physics are a habit of the universe. But all habits (and hence all addictions, which after all, are habits), are things that develop into existence. And once developed, they become controlling by way of strong interdependencies, exerting ‘top-down’ causality on their lower-level parts.

We human beings can overcome our personal behavioral addictions, as I have found. No, I’m not out of the water (or more accurately, the sauce); I’m still an alcoholic. And, I still have a drink on occasion. But only one or two, and only on irregular occasion; I haven’t gotten drunk in seven months. I do have to be careful because every time I do indulge it reminds me of how much I like it, and that’s a dangerous place to go. But it seems to be working for me, so far anyway; the temptation hasn’t been overpowering. I think that one of the key tenets of the twelve step program is true: overcoming addiction requires acknowledging, and linking up with, a ‘higher power’, and I suppose that is what I am doing.

So what is the source of that higher power? If you are religiously motivated, the answer comes quickly enough, but as I’ve already said, that doesn’t cut it for me. For me religion has way too much superstition and prejudicial closed mindedness. True, there are ways to (and adherents who) cut through all that in each of the major religions, but that endeavor always comes up against strong resistance within the religious community, very often leading to marginalization (or worse) of the offending reformer. So as far as I’m concerned, why bother?

The same thing happens in science of course; there is plenty of scientific ‘superstition’. That happens when scientists take the basic assumptions of their field for granted, never questioning them, and as a result, coming to wrong (and typically dogmatic) conclusions about the nature of reality. Like the Newtonian assumptions of absolute space and time, which led physics to the erroneous concept of the ether, an idea that was held tenaciously for decades, and not discarded until that upstart outsider Einstein came along and showed that Newton’s assumption was wrong: space and time are actually the same thing, the measurable dimensions of which are not absolute, but exist in a way that is relative to the speed of light. If you are a photon, there is no space and no time.

But unlike religion, science is an inherently self-correcting system. An Einstein can change the paradigm, virtually overnight, and bring us a little closer to the truth. That is the ultimate value of the scientific approach.

We need science as an approach to life because human beings are hardwired to perceive and interpret phenomena as ‘signs’ of something else (whether or not they actually are); that is, we have a hardwired semiotic tendency that is our biological heritage. Through our consciousness we have developed this creative gift to a new level, which allows us to formulate hypotheses. Left unchecked by empirical verification, this tendency naturally leads (developmentally of course) to superstition and (usually misbegotten) conspiracy theories. When such theories form the dogmatic basis of religion, they grant great power to individuals who are well-endowed with the ability to charm or bully. They become attractors for cults that grow into vast historical movements that entrain social and cultural development. Indeed, they become a higher power that exerts top-down control of appropriately tuned psychologies. So many folks seem happiest when they are led like sheep.

As powerful as it is, it is still superstition, and it doesn’t sit well with those of us who like to try and make deeper sense of things. For us, science is a proven method for cutting through the bullshit (and let’s face it: modern civilization is buried in bullshit). The problem of course is that honest adherence to this path requires healthy agnosticism: that is, an ability to live with (indeed, thrive in) uncertainty. In my experience, that is a rare gift (even, unfortunately, among scientists).

So, where do those of us who can’t stomach superstition find a higher power for overcoming addiction? By itself science is not the answer; but I think that it can be part of the answer. The best science has always been motivated by a desire to deeply understand the universe and our place in it. That’s what motivated Newton, and that’s what motivated Einstein. It also motivated Darwin. And it seems obvious that such understanding grants power.

But not only power to use technology to control nature, which is science’s most obvious application. In the tradition of Greek philosophers, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment, science as a component of the Liberal Arts grants power to become a better human being by overcoming ignorance and enriching culture. Higher power can be found in the pursuit of science that is part of the larger humanistic project involving Art, Literature, Music, History, and Philosophy. And the source of that power is the human community, past, present, and future: all those who participate in development of the Liberal Arts. The higher power is the mutuality manifest in that community.

For a human being, higher power comes from linkage with other human beings. But it goes way beyond that. Ultimately, higher power comes from the mutuality that underlies everything in the universe—in other words, God is Love.

Although I don’t adhere to the dogmatic belief-systems of any of the organized religions, I do have a faith that some may call my ‘religion’. Some may call it naturist. As far as I’m concerned, there is a natural explanation for everything, although we may not now have the capacity to find it. There is nothing outside of nature; ‘supernatural’ only refers to natural phenomena that we don’t (and may never) understand. Perhaps that makes it a semantic argument, but it is an important one, because it brings us back to our natural place in the universe.

Some may call me a pantheist: if there is a God, it is a manifestation of everything, part and parcel, and not separate. It is silly (childish really) to conceive of God as a being (a sexual being at that--otherwise why refer to God as He?) that is somewhere out there, separate.

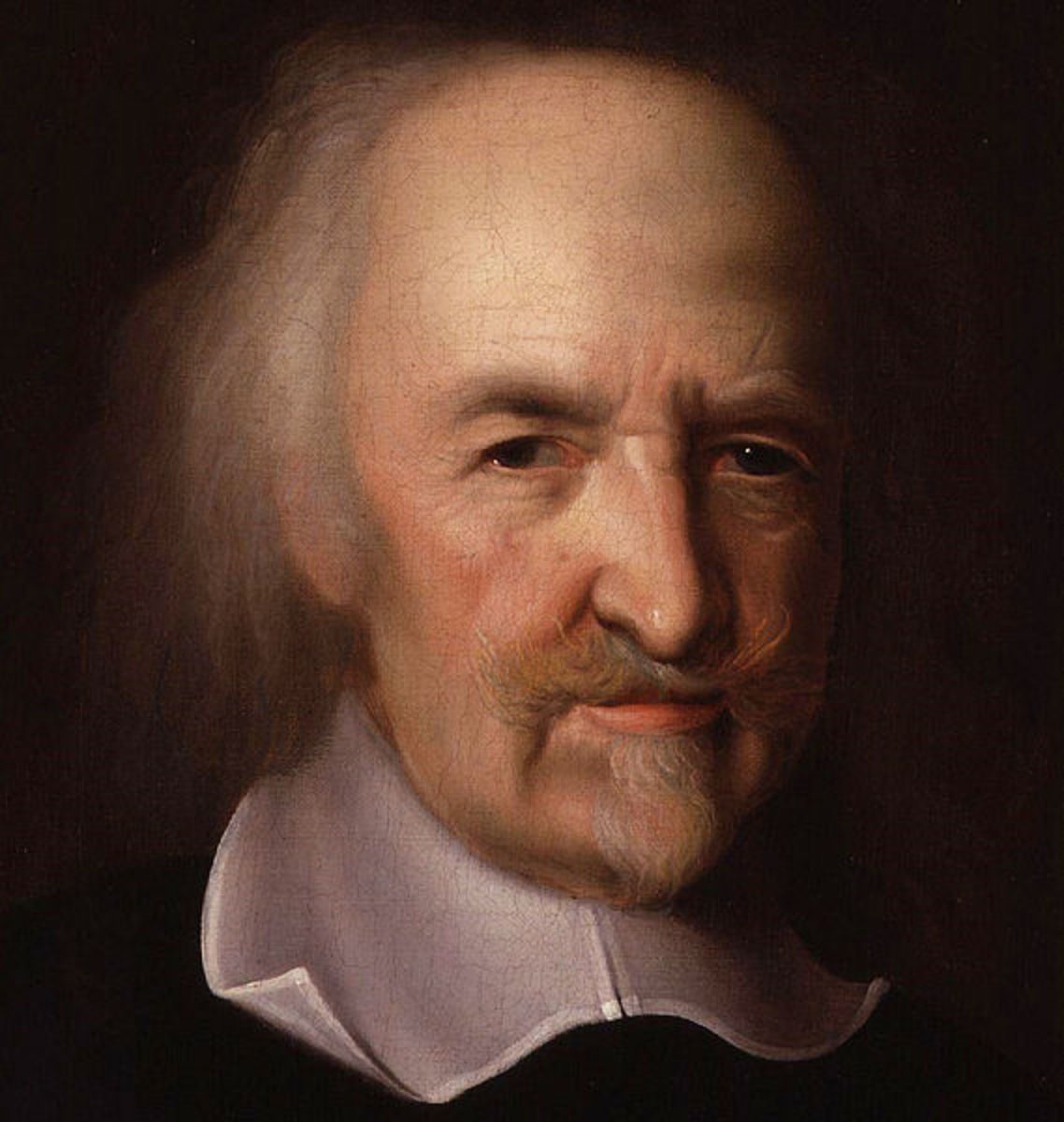

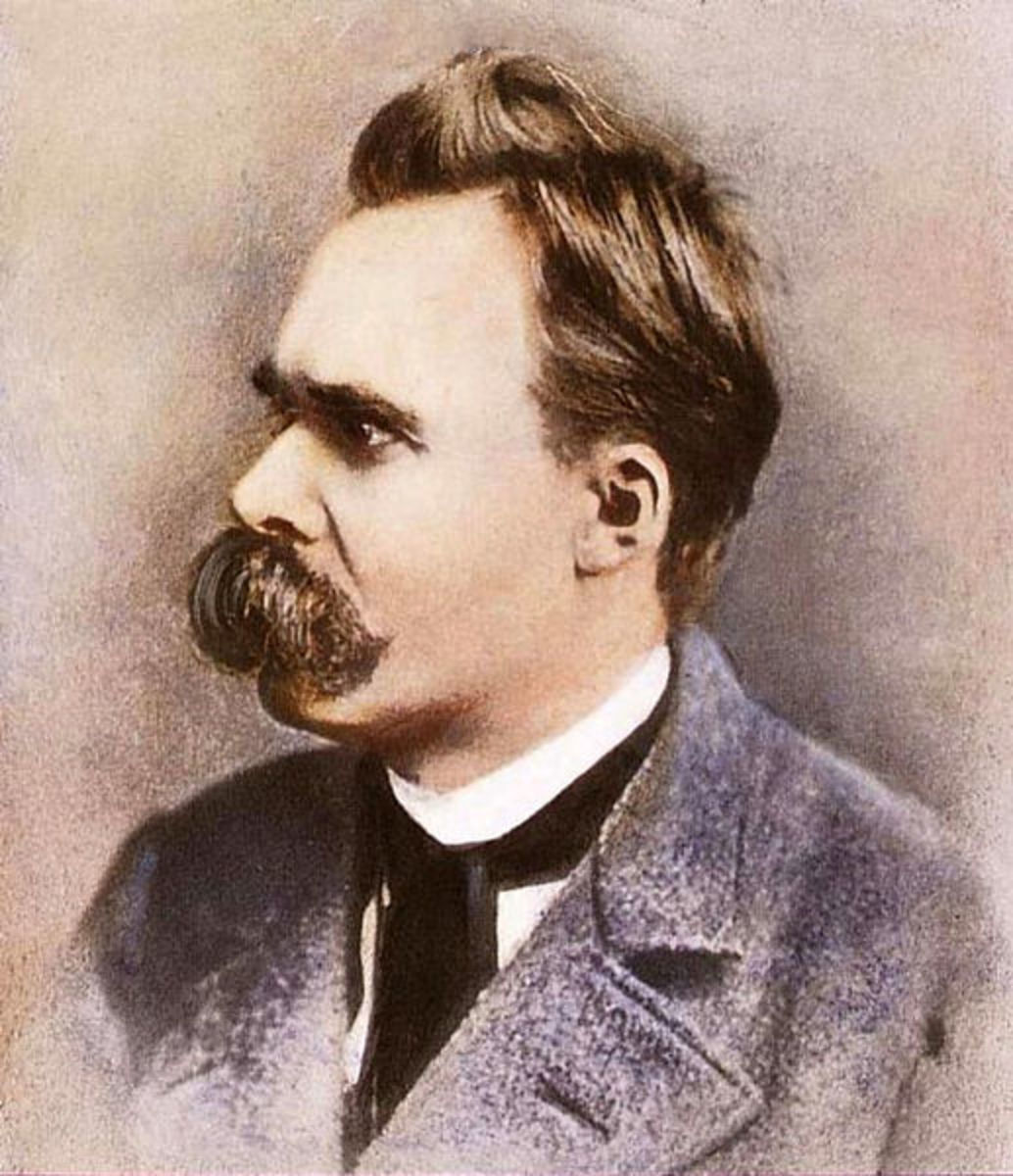

Others may call me a humanist: morality is not determined by an external, supernatural, omniscient authority; it develops from within, and is a human character. That it is so does not in any way diminish it, as Nietsche pointed out.

I am not an atheist. Atheism requires a level of certainty that to me seems absurd in such a deeply uncertain universe. Agnosticism is more my style. But I do believe that there is a higher power in the universe that might be referred to as God. And as far as I’m concerned that power is Love. Love comes from within, and without, manifesting mutuality.

But what does that mean; what is Love?

Love is a resonance into which we can tune. There are many ways of tuning in. Prayer may be one. I’ve found other ways of tuning in, and doing so has helped me overcome my addictions. I experience Love whenever I lose myself in the bliss of a creative process, like playing music (or even better, playing music with friends), or (at times) writing. I find it in reading a good book that speaks to me. I find it in being with my wife and my daughter and my dog. Doing these things takes me away from my urge to drink—they give me access to a higher power.

Not that it’s easy. I’ve spent plenty of time on the dark side, like when things aren’t going my way, or when I am just generally disgusted with the state of affairs. That seemed to happen a lot more just after I stopped drinking. There was a period, back in the beginning of my abstinence, when I was running on faith more than anything else. I had faith that, given time, things would come around. And they did.

I think it’s always like that with Love. Love and faith go hand in hand, and I don’t think you can have one without the other. Jesus was right: human salvation requires both.

But salvation happens here and now, not in the hereafter. It is found in the light side of human nature, the humane side that embraces Love and abhors violence. And it is found in forgiveness.

Although Love stems from the mutuality that is inherent in everything, we humans experience it in a uniquely human way that comes from our social nature. For humans, the most natural road to Love is through other humans.

But, as sentient beings we are not alone in the universe. Whoever or whatever may be out there in the vastness of spacetime, we have many kindred spirits among the other animals here on earth: they are our extended family. And even those most alien to us contribute to our well being. Nevertheless, we are animals with a unique talent. We have learned to dominate nature. With that power, we are as gods to our animal kin. And the light side of our nature, the side wherein our salvation is found, bids that we love and respect them.

As the end of the first decade of the twenty first century draws near, it is amusing to look back at visions of the near-future created in art and literature during the latter part of the twentieth century. I’ve already mentioned one of my favorites, Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odessey”. Another is George Orwell’s 1984. Of those two visions, the latter seems to me to have hit a bit closer to the mark. Doublespeak in public discourse, unending war, hate and fear-mongering in the service of an all-powerful, all-knowing government are the norm, and everywhere we turn we are confronted with thought police (often under the good-intended umbrage of ‘political correctness’). But we haven’t created an artificial intelligence like 2001’s HAL, and we haven’t even been back to the moon since 1972.

In 1989’s “Back to the Future II”, the year 2015 was depicted with flying cars, something that seems laughable now. But a mere 20 years ago, the myth of limitless techno-industrial growth still rung true. As a civilization, we were still over-awed by the technological glories that we had wrought, and most of us bought into the fallacious notion of linear progress. It is understandable of course, given that the unprecedented pace of developmental change driven by industrialized technology had, in the experience of our recent history, seemed to have a linear (and limitless) trajectory. The fact that all this change had occurred within a miniscule sliver of earth’s history, one that would barely be perceptible if the entire timeline was represented as the length of this page, never entered our equations. Ironically, even as the science that wrought all the technological glory painted an increasingly realistic picture with plenty of contextual perspective, our collective gaze remained steadfastly focused on our technologically marvelous navels.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the important fact--the elephant in the room as it were--that we have chosen to ignore throughout recent history is that this developmental explosion of technological change has been driven by the use of cheap energy in the form of fossil fuels. Although no one denies that fossil fuels will run out eventually, the optimists claim that there is more than enough left to give ample time for some genius to come along and invent a new form of cheap energy. Call me a pessimistic nay-sayer, but methinks that kind of thinking fails to grasp the nature of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, and all the logical implications that follow.

The problem with renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, etc.) is that it cannot support our civilization in its present form. The population has grown too big, and the economy has developed too much complexity. The use of renewable energy sources (and more efficient engines) can help prolong the inevitable, but it can’t replace fossil fuel.

The alternative high-grade energy sources are nuclear. Fission is just another non-renewable source with essentially the same problems as fossil fuel: it will run out rather quickly (uranium is already getting scarce), and the entropy production associated with its use will cause great damage to the environment.

But what about fusion? Assuming that a viable fusion reactor may yet be invented (it hasn’t yet), won’t that solve all our problems? I don’t think so. It seems to me that if a civilization such as ours were to begin using nuclear fusion to power our continued growth and development, then the entropic monkey wrenches introduced into the global ecology would lead to our rapid undoing. For one thing, fusion generates a lot of heat and explosive power, and the technology required to contain that power is not simple. How long would the requisite infrastructure last before a major catastrophe? And how many catastrophes would it take to undo civilization? In thinking about these matters, it pays to remember how long life has been around on earth (billions of years), how long humans have been around (less than a million), and how long industrialized civilization has been around (a couple of hundred). Given the Second Law, how realistic is it to expect that we will continue our current high-intensity growth and development into the distant future? I’d say not very—to believe in such progress is akin to believing the literal truth of fairy tale magic. It is the modern day version of alchemy, or of the quest for a perpetual motion machine that dominated 18th century physics.

Listening to the radio the other day I heard that geologists have determined that the amount of change introduced to the earth by humanity will be recorded in its geology, and easily recognizable by any geologists that happen to exist in the distant future. Humanity, by its own collective hands, has brought forth a new geologic epoch: the Anthropocene.

What will be the outcome of this unprecendented change? It’s impossible to predict with any certainty. Throughout earth’s history, the transitions between geological epochs have been marked by drastic and sometimes catastrophic changes, often accompanied by mass extinctions. Some of these were triggered by extraterrestrial debris (asteroids or comets) impacting the earth. But others seem to take the form of collapses from within, driven by changes wrought by life itself. A prime example was the emergence of aerobic life in response to oxygen, which decimated the anaerobic life forms that had developed to maturity in the previous epoch.

Given the deep uncertainty inherent in reality, the specific trajectory of evolutionary change is something that no one can predict, at least not in the long term. But evolution involves development, and development is a trajectory of change that is, by nature, predictable. It always begins in immaturity, and unless it is prematurely ended by capricious happenstance, it will continue through maturity into rigid senescence, ultimately leading to collapse (or death) of the developing system due to its inability to adapt to the incessant, perpetual change that continues unabated. Along the way, development creates context, and context exerts strong top-down control on the constituents of the developing system, control that is difficult to overcome from the bottom up. Like everything else, civilizations develop over time, creating constraints that control the activity and historical movements of humanity. There have been many civilizations over the history of humans, none of which has lasted. Why should ours be any different?

In short, the transience of modern reality is quite predictable, as is the end of our current civilization and global economy. What we can’t predict is what form the end will take. Will it be a tragic, catastrophic collapse or a relatively painless transformation into something new and different?

With each passing day that goes by like the last (i.e., business as usual), the former scenario becomes more likely. Collapse of the global economy will likely create an economic depression that makes that of the 1930s seem like a cakewalk. Very few of us know how to live without the accoutrements of modern civilization: the coming withdrawal will undoubtedly be a nightmare. The most worrisome aspect is the violence. For all of our technology, we seem to have evolved little beyond other animals when it comes to competition for scarce resources: more often than not, we’d rather kill than share. And we’ve got technology that makes it so efficient.

What will emerge on the other side of the end is not as predictable as the fact that there will be an end with another side. Although we have technologies that could destroy most life on earth, I have faith that whatever happens, in one form or another life will live on. Whether human life survives is more uncertain. Personally I can’t imagine a transition that doesn’t involve a lot of bloodletting. But I like to hope that with the survivors the seed of a more enlightened humanity will emerge. I’m pinning my hope on the human capacity for Love. Without it, there is no hope. With it, a sustainable future that is not a living hell may yet arise from the ashes following the collapse of our senescent civilization.

But to make it happen, we have to start now. We need to plant the seeds, to begin developing new systems from the bottom up—new institutions and communities that understand ecology and recognize that the only heaven relevant to our lives is that which we create here on earth, through Love. An immature cultural ethos moving in that direction re-emerged in the 1960s, although it seemingly went into decline after the 1970s as Americans embraced the blissful, backward-looking denial of Reaganism. But a culture of Love is still growing in pockets here and there. With any luck it will develop a level of maturity sufficient to sustain it through the hellacious change that lies ahead. Because ready or not, here it comes.

Are you ready?