- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

A Forgotten War: the U.S. & Mexico, 1846

American Civil War or World War II history is well-known and celebrated throughout the U.S. We are also familiar with the current conflicts and recent engagements of the 20th Century. Lesser known are the other wars of the 19th Century. These three wars, in Mexico, Cuba and the Philippines, are important not just for what happened - but what could have.

Prelude to War

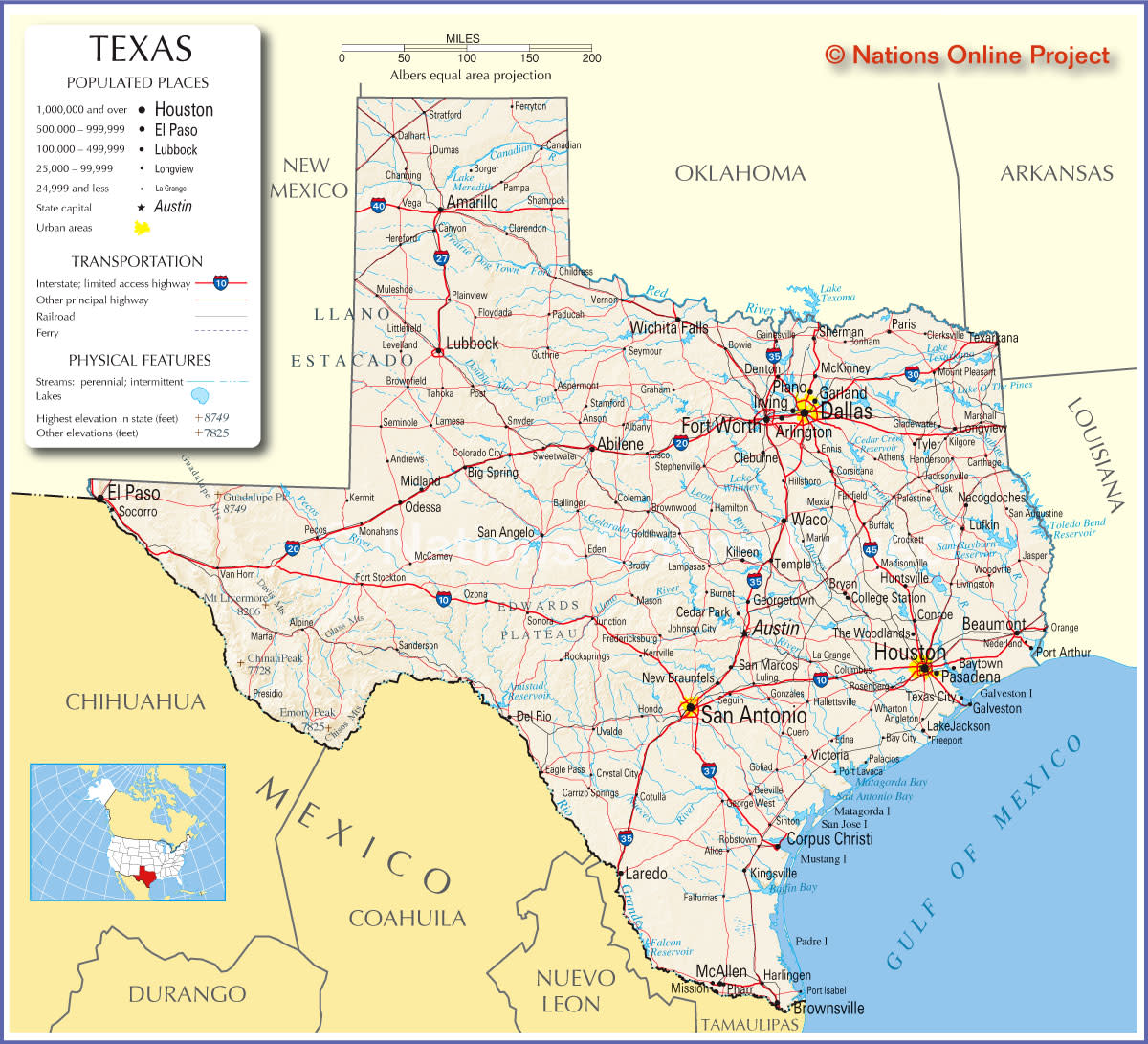

In 1836 the current state of Texas was still a province of Mexico. For years American settlers had been coming to the area under President James K. Polk's goal of "Manifest Destiny" - the desire to see America extend from coast to coast. Fearing calls for Texas independence, governor General Antonio de Lopez Santa Anna attempted to crush the nacent rebellion which resulted in the battle of the Alamo. The slaughter of luminary figures Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett incensed Texans, Santa Anna was captured and Texas declared independence as the Lone Star Republic.

But Texas did not join the U.S. until 1845. Turmoil within the Mexican government had gotten them deeply in debt and various factions were not united in how to proceed. What they were united in was their opposition to Texas joining the U.S. The Mexican government had never recognized the Lone Star Republic's independence and thought they would eventually retake the territory. To that extent they had warned the United States that annexing Texas would mean war.

When Texas joined the United States in December of 1845, ambassador John Slidell was sent to Mexico to offer $3 million dollars as a purchase price along with an offer to forgive debt owed U.S. citizens for damages caused during Mexico's war for independence from Spain. The Mexican government was in no shape to consider the offer, having changed presidents four times. However, the various factions were united in their refusal to hand Texas over without a fight, and Slidell returned to the U.S. with a flag of war.

Conflict in Mexico

President Polk declared war on May 11, 1846. The war was not universally supported by Americans, with some abolitionist and Whig voters feeling this was an attempt to expand slavery. But America's professional military was dispatched and in short order had routed the Mexican forces in nearly every engagement. The Mexican Army under Santa Anna suffered from high desertion rates and was ill-supplied by the fractured government.

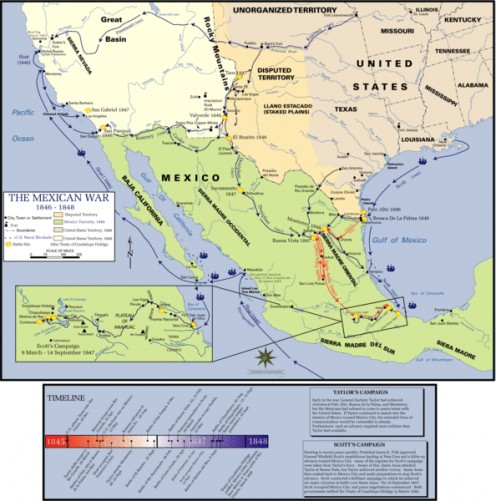

The war took place in three major arenas: California, Texas and the Mexican heartland. In California John C. Fremont lead the "Bear Flag Revolt" that threw off the Mexican governorship and established California as an independent republic. Commodore John Stockton brought a naval fleet into Monterey and ground forces under Stephen Kearney fought tough battles. By 1847, California had been secured.

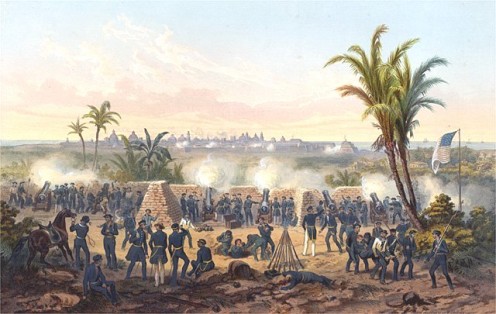

In Texas, General Zachary Taylor brought ground troops across the Rio Grande, where they faced Santa Anna. At the same time, an expeditionary force under General Winfield Scott landed on the Mexican shores of the Gulf of Mexico at Vera Cruz and drove towards Mexico City. The design was to join forces together at the capital. The Battle of Chapultepec, an ancient fortress outside the city, decided the outcome.

On August 7, 1847, the U.S. Army captured Mexico City and the war was ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. Mexico ceded it's claims to Texas, and the majority of the southwest including California and all the land between Wyoming, Colorado and the current southern border of the United States. In return the U.S. paid $18 million dollars and assumed some of Mexico's debt.

Outcomes of the War

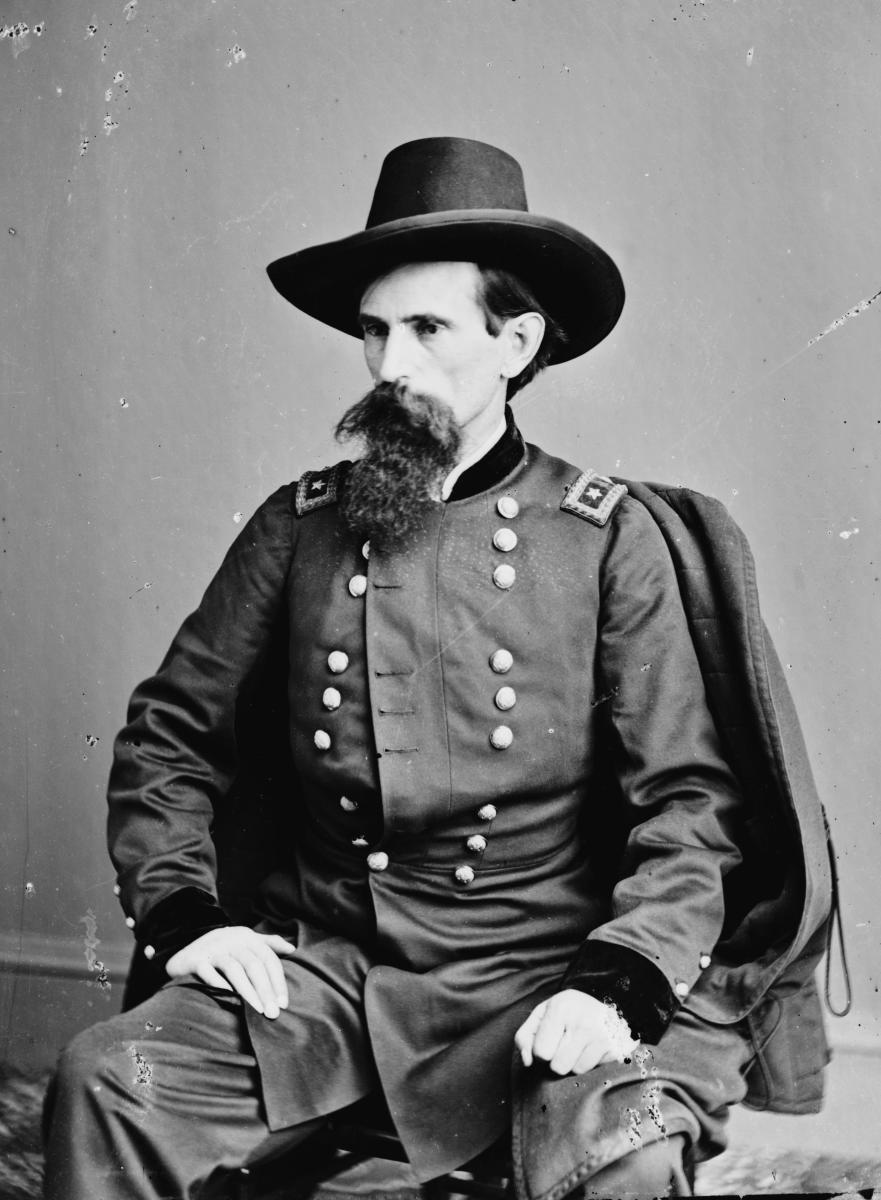

The Mexican-American war was the first real field test of America's modernized professional military, led by officers who had attended academies like West Point and the Virginia Military Institute. It created heroes like Zachary Taylor who went on to become president, and it battle-hardened the later combatants in the American Civil War. Future generals Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, Sherman, McClellan, Burnside, Longstreet and Confederate President Jefferson Davis were all young officers and soldiers in this conflict.

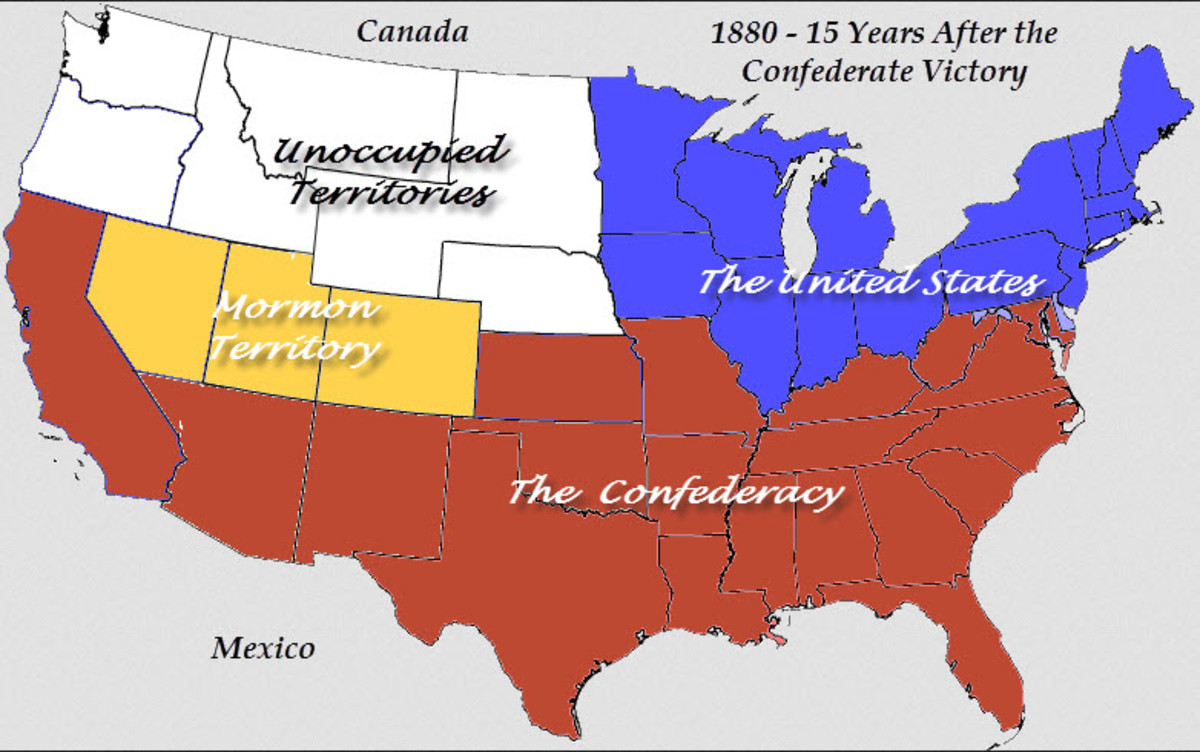

What could have happened, but didn't, is the total annexation of Mexico by the United States. With control of the capital and government, the U.S. could have annexed a much larger territory or controlled Mexico as a puppet government or colony as many European powers were doing with Africa and the Far East. But there was great public outcry and opposition to the annexation of even California because many Americans didn't want to be seen as an empirical power. Having fought fifty years earlier for freedom from an empire, they were not ready to become one themselves. This fervent rejection allowed Mexico to retain her sovereignty. But what would a map look like today if Polk's administration had pursued such a course? Would the Mexican states be the sixty-plus states of the U.S.? Or would the addition of so pro-slavery inhabitants south of the Mason-Dixon have augmented the Confederacy in the Civil War so they could have succeeded in secession?