24 Reasons Why the “Golden Age” of Japanese Film Really WAS Golden (Part III)

![Otama (Hideko Takamine) is confronted by the rich man who keeps her, Suezō (Eijirō Tōno) in Shirō Toyoda's Wild Geese [aka The Mistress] (1953) Otama (Hideko Takamine) is confronted by the rich man who keeps her, Suezō (Eijirō Tōno) in Shirō Toyoda's Wild Geese [aka The Mistress] (1953)](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/12004702_f520.jpg)

10. Wild Geese [aka The Mistress] (Gan) (Dir: Shirō Toyoda, 1953)

This is the sort of sensitive character study – a love story without sex or even any open acknowledgement of love – that the Japanese once did supremely well… and that Hollywood has almost always done badly. In the Meiji Era (late 19th Century), a young woman, Otama (Hideko Takamine), is virtually sold to a middle-aged moneylender named Suezō by her father to save her family from destitution. Otama goes along with the deal because she vainly hopes Suezō will marry her and make her respectable. (She believes the already married man is a widower.) Meanwhile, she falls in love, platonically, with a sensitive university student, Okada (Hiroshi Akutagawa), who passes her house each day. However, Okada, though clearly attracted to the kept woman, plans to leave for Germany to study medicine. Director Shirō Toyoda handles what might have been a rather sordid tale with grace and admirable restraint. But what really sets this film apart from Hollywood convention is the depiction of Suezō, played by the wonderful character actor Eijirō Tōno. In an American picture, Suezō would surely be depicted as irredeemably evil. But Tōno, under Toyoda’s sure direction, portrays him as an almost sympathetic character. He’s a liar, usurer and adulterer, true, but he also loves Otama in his inept, pathetic way… a love that, like hers for the student, is doomed never to be fulfilled.

11. Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijū-shi no Hotomi) (Dir: Keisuke Kinoshita, 1954)

This film is not only Kinoshita’s most popular work, but one of Japan’s most beloved movies. At a rural island community in the late 1920s, a new schoolteacher from the city, Miss Ōishi (Hideko Takamine), arrives to instruct the local schoolchildren, who are delighted with her. (There are twelve students in each class: hence, “twenty-four eyes.” The number “24,” by the way, also inspired the title of this article.) But the fascist dictatorship soon takes power, and the morally righteous Miss Ōishi needs to decide whether she can continue to teach while her country prepares for war. As the critic Tadao Sato rightly claims, Takamine’s heroic teacher is too good, too idealized. He also points out that the film portrays the Japanese as pure victims of tyranny and refuses to raise the thorny issues of complicity and war crimes. However, Kinoshita, a gifted and conscientious craftsman, has cast the movie very cleverly. Since the heroine is shown teaching the same children at different grade levels, Kinoshita carefully auditioned pairs of look-alike siblings, five or six years apart in age, to play the schoolchildren. The audience thus seems to watch these cute kids grow up before its eyes, and the sense of an entire generation wasted by poverty and war becomes overwhelming. The ending, with Miss Ōishi, now a middle-aged woman, visited by her sad, surviving former students, is one of Japanese Cinema’s most memorable “three-handkerchief” scenes.

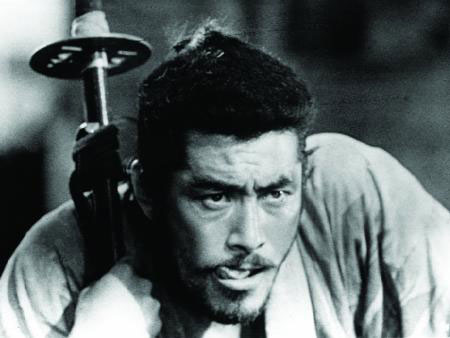

12. Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai) (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

What can possibly be said about Kurosawa’s greatest masterpiece – the cinema’s most stirring epic drama and, in my opinion, the finest movie ever made – that hasn’t already been written? Perhaps one can note that this tale of seven real and wannabe samurai who protect a 16th Century peasant village from bandits is the supreme example in Japanese Cinema of its admirable craft tradition, which began in the 1920s. Kurosawa demonstrates here how much he had learned from the masters of the period film who preceded him: Mansaku Itami, Sadao Yamanaka and, of course, Kenji Mizoguchi. But he also shows what he absorbed from European and American artists like Sergei Eisenstein, Jean Renoir and John Ford. In the creation of any film, there are four stages: the script phase, the pre-production phase, the actual shooting and the editing phase, and it should be obvious to anyone who has seen Seven Samurai that Kurosawa was a master of the script and shooting phases. But Kurosawa’s toughest self-imposed challenge on this picture involved its pre-production work. Before a foot of film was exposed, the director created whole notebooks – dossiers, so to speak – containing fantastically detailed information not only for his heroes, but for even the most minor characters, giving them all an incredibly vivid, three-dimensional reality. But it is the movie’s matchless editing that sets it apart from any other Japanese film. An anonymous reviewer for Time magazine once wrote, “Again and again, Kurosawa sends a dark thrill through his audience with a touch of sensuous physical reality.” Yet it is precisely the masterful juxtaposition of physical details, achieved through editing, that creates those dark thrills. Because of all these factors and more, Seven Samurai is great art that happens also to be great entertainment.

13. Sanshō the Bailiff (Sanshō Dayū) (Dir: Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954)

In 2009, Japanese Cinema buffs in the West were outraged when the distinguished film publication, Kinema Jumpo, released its list of the top 199 (sic) Japanese movies of all time, and Mizoguchi’s wonderful Sanshō the Bailiff was nowhere to be found. Can the knowledgeable Western fan dare claim superiority over Japanese critics? In this case, definitely yes! In Heian period Japan, the wife (Kinuyo Tanaka) of a wrongfully banished official and their two children – a son, Zushiō, and a younger daughter, Anju – set out across dangerous countryside to reunite with him. On the way, mother and children are captured by slave traders, sold and separated. Brother and sister are placed in a slave compound under the rule of the evil Sanshō (Eitarō Shindō). Grown to adulthood in this hell, Zushiō (Yoshiaki Hanayagi), now a cruel overseer, faithfully serves Sanshō; it is, he thinks, the only way to survive. However, Anju (Kyōko Kagawa) retains her parents’ ideals of justice and mercy, and her heroic sacrifice enables Zushiō to escape. There follows a devastating scene. Zushiō arrives at the capital, Kyoto, to try to notify the authorities of Sanshō’s wickedness. But those officials are too caught up in their pomp and ritual to care, and they continue to march in procession, like high priests, totally ignoring Zushiō’s desperate cries. It is a chilling image of the indifference of government to the sufferings of the people that remains sadly relevant.

14. Floating Clouds (Ukigumo) (Dir: Mikio Naruse, 1955)

Perhaps the finest work by neglected master Mikio Naruse, Floating Clouds, in my experience anyway, divides Japanese and Western movie fans like no other Japanese picture, even Sanshō the Bailiff (see above). In the very same 2009 Kinema Jumpo poll that excluded Sanshō, Floating Clouds amazingly placed third, right after Tokyo Story (see Part II) and Seven Samurai (see above). Whereas most Japanese appear to perceive great tragedy in this tale of an adulterous couple who start an affair in wartime Indochina and continue it in postwar Japan, an American viewer might easily see mere soap opera. This is deceptive, though. The important thing to grasp is that, soon after returning to Japan, Yukiko (Hideko Takamine) loses all illusions about her lover, Kengo (Masayuki Mori). He is lecherous, feckless, shiftless and cowardly… and she knows it. But she keeps on with the affair past the point of sense or even sanity. By doing so, she remains true to her dream memory of Kengo in Indochina even though she now knows it was all an illusion, rather than accommodate herself to the dreary reality of postwar Japan. Therefore, when Yukiko reaches the end of her self-destructive path, the scene is both horrifying and noble, even romantic: for love, the heroine has cast off all her chains, even those of life itself.

(Continued in Part IV)