24 Reasons Why the “Golden Age” of Japanese Film Really WAS Golden (Part IV)

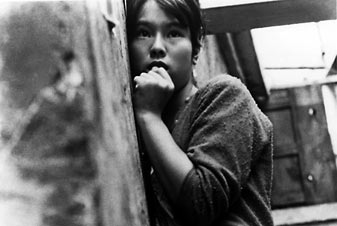

15. The Lower Depths (Donzoko) (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

Difficult as it may be for some theatre fans to accept, I really believe that this movie can claim a higher place in the history of cinematic art than its prestigious source – the play Na Dne by Maxim Gorky – holds within the history of drama. (The Lower Depths, by the way, is an inadequate translation from the Russian. “Na Dne” means “at the (very) bottom,” so the title perhaps ought to be translated as “The Lowest Depths,” that is, the nadir to which a human being can sink.) The director has masterfully transposed Gorky’s tale of penniless human flotsam uneasily sharing a Russian flophouse to mid-19th Century Japan, just before the Meiji Restoration – a time of great change and even greater suffering. Kurosawa’s bravura use, within a highly restricted set, of the multiple camera technique he mastered in Seven Samurai (see Part III) makes each brilliantly-written set piece work both dramatically and as cinema. He also wisely dropped Gorky’s concluding polemical harangues, and came up with a more logical, humorous and powerful ending than the original, one which reportedly took his actors weeks to rehearse. The director has here assembled the most extraordinary and cohesive ensemble cast (excepting only that of Seven Samurai) that he would ever work with. To cite only the most outstanding performances, attention should be paid to Kyōko Kagawa (in her first of five roles in Kurosawa’s films) as the confused heroine, Kōji Mitsui as a seemingly nihilistic cynic and, above all, Kamatari Fujiwara as the alcoholic actor. In its completely confident style and its consistently sustained tone, The Lower Depths is surely Kurosawa’s most underrated film.

16. Tokyo Twilight (Tōkyō Boshoku) (Dir: Yasujirō Ozu, 1957)

In the mid-1950s, Yasujirō Ozu briefly changed significantly the subject matter and tone of his films. As scholar David Bordwell points out, to reach the youth audience, Shochiku Studios was pressuring its directors, including Ozu, to cast more young stars in their pictures and to bring the “home drama” genre up to date. But the influence of Mikio Naruse on Ozu may also have been a critical factor. Naruse’s 1955 film Floating Clouds (see Part III) had made a huge impression on Ozu. (In his journal, he called it a “masterpiece” – very rare praise from him.) So it’s probably no coincidence that, with Tokyo Twilight, Ozu embraced Naruse-type melodrama as never before. For example, the Setsuko Hara character, Takako, who is tired and miserable like a typical Naruse wife (and very unlike an Ozu “good daughter”), has abandoned her cold, insensitive husband. Meanwhile, her younger sister, Akiko (Ineko Arima), has fallen in with a bad crowd and gotten herself pregnant. But Akiko goes completely off the rails when she discovers that her scandalous mother (Isuzu Yamada), who long ago deserted the family for another man, and whom she thought had died, is actually alive and running a nearby mahjong parlor. Japanese critics at the time totally rejected this ultra-dark variation of the typical Ozu family drama. However, I greatly admire this movie, both in itself and for the courage Ozu showed in going outside his comfort zone. Akiko is more of a lost soul than any other Ozu character and, as played unsentimentally by the beautiful Arima, her fate is heart-rending. Ozu had apparently wanted to criticize the younger generation through the figure of Akiko, but, humane artist that he was, he wound up blessing the character he had intended to condemn.

17. Conflagration (Enjō) (Dir: Kon Ichikawa, 1958)

This bleak psychological character study, part of a series of such films Kon Ichikawa made in the 'Fifties and early 'Sixties, is based upon a novel by Yukio Mishima, which itself was based upon an actual crime. A young, neurotic Buddhist acolyte with a nasty stutter (Raizō Ichikawa) is caught by police after having burned down a legendary temple… one he’d always admired and loved, even worshiped. The movie then flashes back to reveal the motive behind the boy’s mad act. What’s most distinctive about this movie is that, though it looks and feels like a (very elegant) horror movie, it plays like black comedy. (Pauline Kael shrewdly observed that Ichikawa’s films consistently make audiences laugh without knowing why they’re laughing.) Through the acolyte’s horrified eyes, we observe the greed, lust and overall sleaziness of those who profit from the beautiful temple’s popularity. Whenever we think that the people around this unlucky young man couldn’t possibly get any more venal and appalling, they do. Even more distinctive than the film’s satiric tone, however, is its style. Japan, perhaps more than any other country, fully exploited pictorially and dramatically the widescreen format. In Conflagration, Kazuo Miyagawa’s brilliant cinematography adds immeasurably to the tale’s impact, particularly in the haunting scene of the temple burning. Through his dramatic skill, polished style and perverse humor, Ichikawa turns what might have been a mere cautionary tale about a puritanical fanatic into an eloquent elegy over the corruption of Japan.

18. Pigs and Battleships [aka Hogs and Warships] (Buta to Gunkan) (Dir: Shōhei Imamura, 1961)

The story goes that, as a young assistant director at Shochiku, Shōhei Imamura got himself assigned to the set of Ozu’s classic film Early Summer (see Part I). Though such a job might seem a dream gig to most film fans, Imamura hated the experience, finding Ozu’s methods and particularly his direction of actors distasteful. So from the beginning of his own career as one of the first “New Wave” directors, Imamura set out to be the anti-Ozu, his movies as unlike the older master in subject matter, camerawork and acting as humanly possible. This raucous, satirical tale of gangsters and oversexed women is typical of this early work. The basic plot is unremarkable: in postwar Yokosuka, the site of a US naval base, a young girl, Haruko (Jitsuko Yoshimura), tries to persuade her boyfriend to save himself from the yakuza gang he’s been working for. But the film was unusual in its time for celebrating the survival skills of its working class characters. Though I love Ozu’s work, I also have a soft spot for Imamura’s very different vision of the Japanese. Haruko represents one of the first in a long line of strong, self-assertive Imamura women, who make a refreshing contrast to Mizoguchi’s and Naruse’s masochistic heroines. The climactic scene in the film – a literal stampede of black market pigs – has to be seen to be disbelieved.

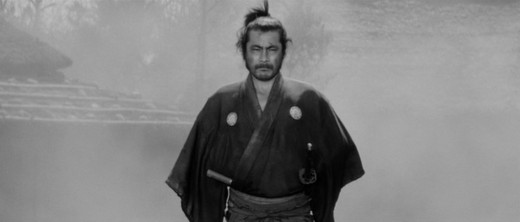

19. Yōjimbō [aka The Bodyguard] (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1961)

What’s remarkable about Kurosawa’s films of the 1960s is how quickly he got the point of New Wave filmmakers such as Imamura (see Pigs and Battleships above), with their anti-authoritarian irony and explicit violence. And as this movie became the most violent and nihilistic samurai film ever made up to its time, it’s hard to resist the suspicion that with Yōjimbō, Kurosawa was trying to beat the younger men at their own game. In mid-19th Century Japan, Sanjuro (Toshirō Mifune), a dirty, cynical, rootless samurai, wanders into the ultimate one-horse Japanese town, where rival merchant clans, both awful, battle for supremacy. Just for the hell of it, this killer-for-hire interjects himself into the local war and helps the two sides wipe each other out. Though Mifune was about 40 when he made this, he risked ridicule (and a coronary) with the intensity of the fighting skills he was called upon to display, and his extraordinary energy together with his razor-sharp comic timing made his performance here a triumph. As Kurosawa (and Mifune) biographer Stuart Galbraith IV notes, it was this film above all others that fixed forever the image of Mifune in the public mind, both in Japan and abroad (as the late John Belushi could have confirmed). And as Donald Richie has written, this is also the master’s most handsomely-shot film, a powerful collaboration between two great cameramen: Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon: see Part I) and second unit lensman Takao Saitō, who would be promoted to full cinematographer with Kurosawa’s next film – Yōjimbō’s sequel, Sanjuro.

(Concluded in Part V)