Contrasting Views on Democracy of Tocqueville and Jefferson

America is known as the land of the free. It is written in the national anthem and boasted to other nations around the world in the form of bald eagles and bold flags. But does our freedom come at a cost? Thomas Jefferson’s “Declaration of Independence” asserts that liberty and equality are the absolute necessary principles upon which the United States should be founded. In contrast to Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville offers a realistic, slightly cynical view in his work Democracy in America. He argues that America’s democracy is not as utopian as many people would like to think. Both documents are still very relevant in today’s society, in which there seems to be a constant battle between equality and freedom – two ideals that should go hand-in-hand, but rather seem to oppose one another. As Americans feel the need to make life absolutely equal and “politically correct”, others are at risk of being stripped of their basic freedoms. While Jefferson is right to value liberty and equality, Tocqueville’s prophetic writing predicts the types of problems that are occurring in America today.

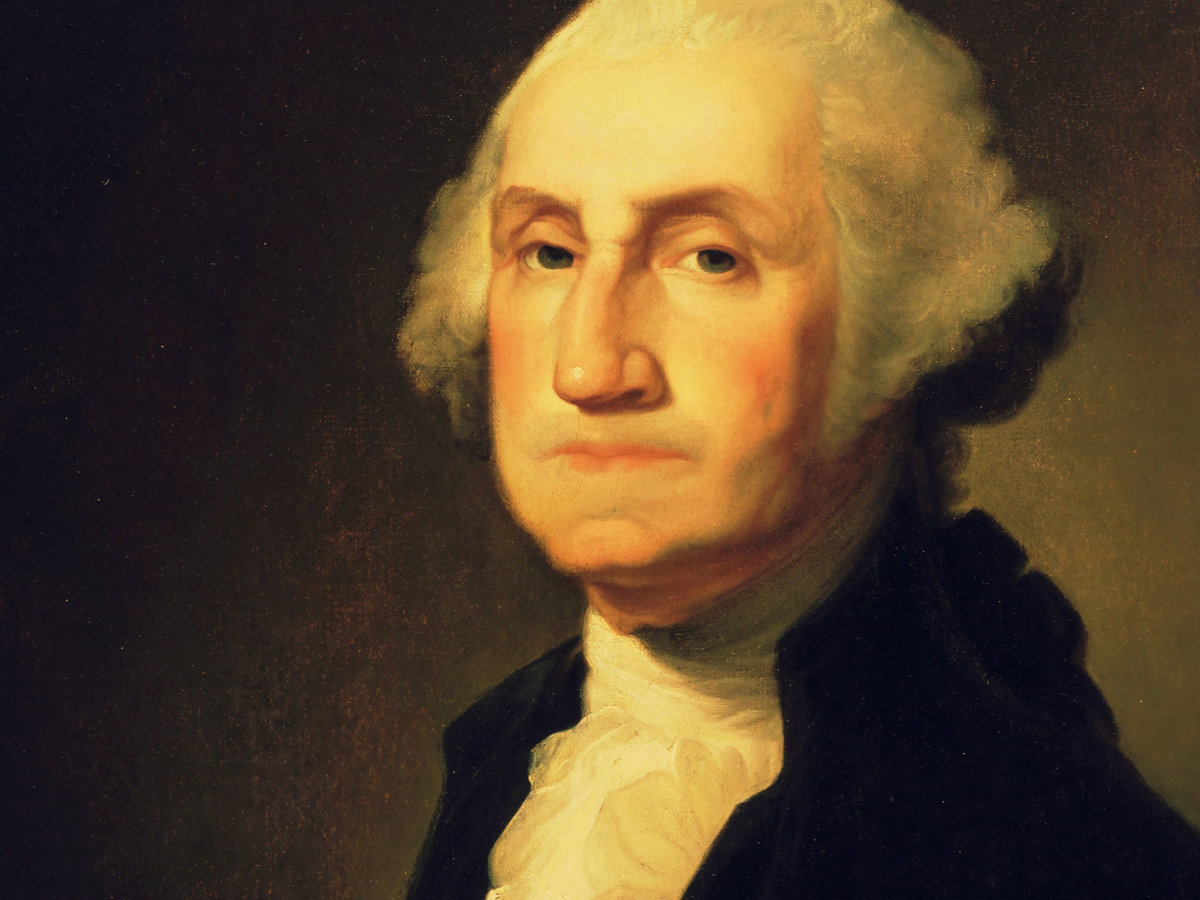

Thomas Jefferson, one of America’s founding fathers, plays a very influential role in acquiring our nation’s freedom. As a drafter of the “Declaration of Independence”, a document that announces to the world the intention of the United States to separate from Great Britain, he makes history in establishing what would become the world’s most famous democracy. Although he does not mention the word “democracy” anywhere within the declaration, it is obvious that he intends to instill a form of government which fairly represents the people: “To secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” (Jefferson). While the founding fathers do not have the details of the future government worked out, a democracy is a clear choice in allowing the citizens to have control over their own government, unlike the style of government forced upon the states by Great Britain. The most famous lines in the “Declaration of Independence” insist that all people are both equal and deserving of certain rights, the most important being liberty: “All men are created equal, [and] they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” (Jefferson). These two key ideas lay the groundwork for future laws and policies in the United States, while ideally protecting citizens from an oppressive government. However, how can one insure these freedoms and demand equality without some restrictions made by the government?

Alexis de Tocqueville shrewdly acknowledges the inconsistencies in the foundational principles of the United States. In describing his enlightening visit to America, Tocqueville conveys the first qualities he notices: “It is not impossible to imagine the great freedom enjoyed by Americans and one can also form an idea of their extreme equality but it would not be possible to understand the political activity prevailing in the United States without having been a direct witness of it” (Tocqueville 183). His use of the phrase “extreme equality” and the observation that it required “political activity” conveys that even in 1831, when Democracy in America was published, Americans were obsessed with the idea of equality and political correctness. Although Tocqueville points out several strong points of American government, he does not hesitate to criticize it: “The laws of American democracy are often defective or incomplete; they sometimes violate acquired rights or give a sanction to others which are dangerous. Even if they were good, their frequent changes would still be a great evil” (Tocqueville 170). In addition to these problems, Tocqueville points out that although a democracy runs based on the will of the majority, the majority does not include everyone, and therefore some people, as many as 49%, may not get what they want (Tocqueville 272). This potentially leaves a large portion of the population out of the realm of influence in the government, essentially forcing them to give up, or at least temporarily put on hold, their ideals and wishes.

Since citizens in America have the ability to influence their own laws, it seems likely that they will want to use that ability to better themselves. This causes everyone to strive to be on par with the person who is the wealthiest or has the most advantages, especially since it is promised in the “Declaration of Independence” that they have the right to be equal. However, only those within the majority are able to have their voice heard and therefore have the opportunity to gain “equality”. In the past, the civil rights movement fought for equality in both daily life and government representation for the African Americans. In order for African Americans to gain equality, the “liberties” of slave owners had to be taken away. Today, similar struggles are seen in movements supporting both marriage equality rights for all sexualities and reproductive rights for women. To give these groups equality would trample on the “liberties” of mostly religious groups who oppose them. The word “liberties” is in quotation marks because recently, some religious groups have shown opposition to the freedoms of others, even though people of religious faith have no more freedoms, influence, or superiority over those of no religion, based on the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights. Remarkably, Tocqueville predicted exactly the acrid reaction that one can witness today: “By a strange combination of events, religion is temporarily involved with powers overturned by democracy and it often happens that it repels that equality it loves and curses freedom as an opponent would” (Tocqueville 21). While most religions tout the importance of loving others equally, many suffer from failure to back these claims, especially when not in strict adherence to their specific dogmas, resulting in hypocrisy. If such factions were to remove their religious related influence from government, per the First Amendment, the majority would no longer have a reason to deny marriage and reproductive rights to the respective movements. However, it seems unlikely for this to happen in the near future because Americans feel the need to be politically involved not only in their own life, but in the lives of others as well: “In contrast, if an American were to be reduced to minding his own business, he would be deprived of half his existence; he would experience it as a gaping void in his life and would become unbelievably unhappy” (Tocqueville 184). Tocqueville accurately describes the intrusive tendencies of Americans, which is still very true today. This general nosiness where it concerns the freedoms of others and the demand to have their liberties protected above all else are basic causes of the major conflict between the freedom of the majority and equal rights of the minority.

If he were around today, Tocqueville would not be surprised in the least at the problems America is facing. Although Jefferson praises, and nearly worships, the ideas of freedom, equality, and liberty, he does not contemplate the consequences that result from too much of a good thing. In contrast, Tocqueville, who is both wise and perceptive, is able to foresee the problems that would later plague America, including the paradox of freedom and equality. His observations and assertions in Democracy in America are as relevant today as they were when he first developed them. Because of this, Tocqueville will be remembered throughout history as a foreign sage who saw through the flourishes of American democracy and called it as it was: a country with a flawed government, just like the rest of the world.

Works Cited

Jefferson, Thomas. Declaration of Independence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. New York & London: Penguin, 2001.

Your Turn

Who do you think was more prophetic or correct in their views on democracy?

Related Essays

- Marx's Influence in America

An analysis of Marx's Communist Manifesto and how it is applied in America today. - Division of Labor in America

An analysis on Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations"; specifically his claim that the division of labor increases efficiency, as well as how that has played out in the Industrial Revolution and today. - Power and Control in Future Societies

Based on short stories from Kurt Vonnegut's "Welcome to the Monkey House", I have come to several conclusions relating to power and control in future societies. - Analysis of W.E.B. Du Bois' "Double Consciousness and the Veil"

An analysis of the struggle for equality and inner turmoil among African Americans as described by W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk: Double Consciousness and the Veil. - Imagery in "I Have a Dream"

An analysis of the imagery used in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s most famous speech, "I Have a Dream" and why it was so effective.