On Principle and Pragmatism VI: What is the Role of the Supreme Court?

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

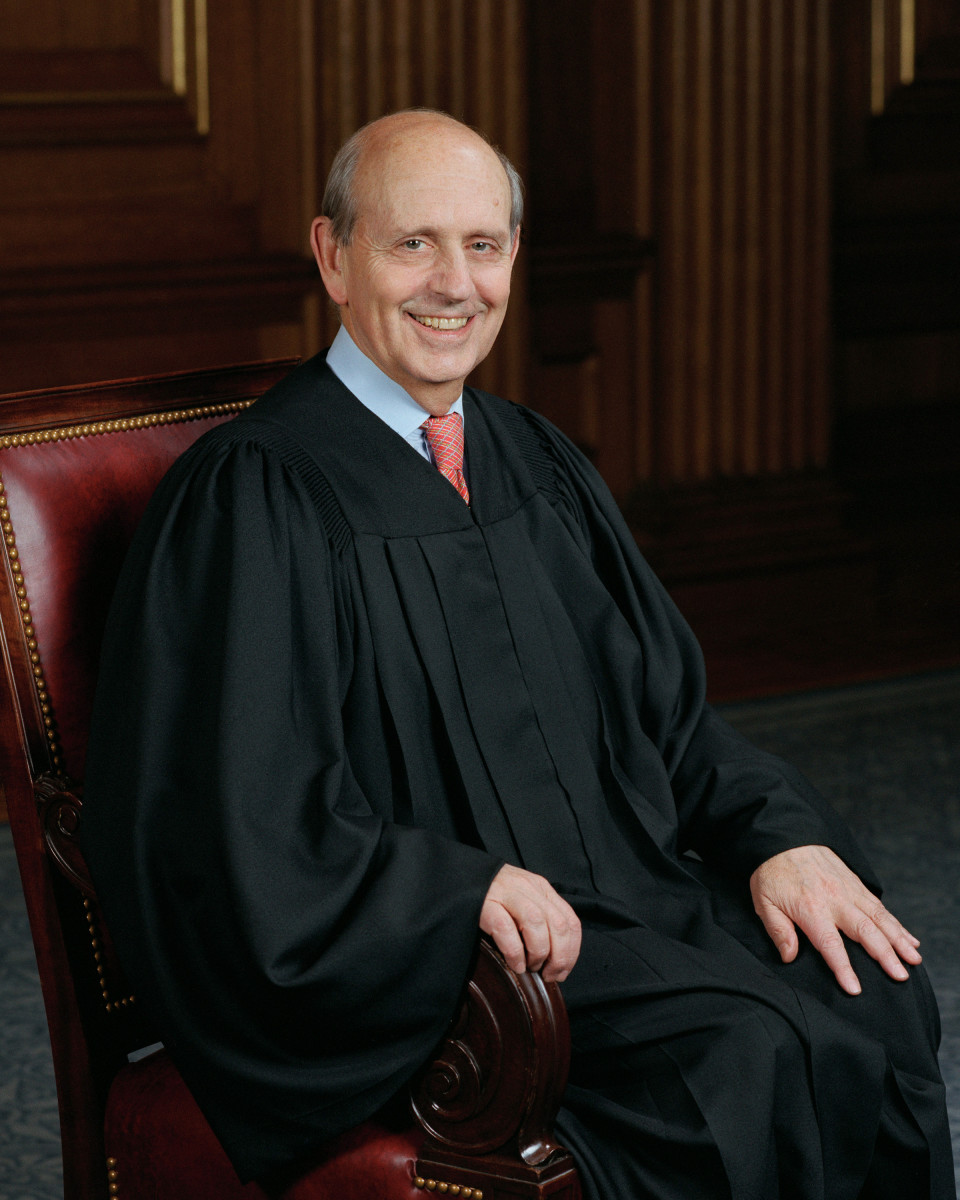

[Much of the details (marked with a *) of this hub are from Supreme Court Justice's new book, "Making our Democracy Work", (shown in the Amazon ad to the right) where he provides proper referencing as appropriate. The hub's color and opinions are my own. - ME]

TO UNDERSTAND HOW THE DEBATE over the role of the Supreme Court came to be, one must understand the history from whence it came. In a poll question in another of my hubs, I asked if the readers agreed with the following statement, "The Founders, in writing the Constitution, intended for the Judicial Branch to have equal Power with Congress." So far, to my surprise, two Liberals answered No, one Moderate answered Yes, another No, and three Conservatives answered Yes (the surprise). The actual answer is ... it doesn't look like it, initially at least. Has it grown to be so? No question in my mind about that it has.

On June 21, 1788, the U.S Constitution was ratified by the ninth state, New Hampshire, and a new country was born that consisted of a single central government, given certain powers and made up of three branches; executive, legislative, and judicial, while, at the same time establishing a new federal relationship between this new, more powerful central government and its constituent states. One of the hallmarks of the new Constitution was the inclusion of "checks and balances", especially between the executive and legislative branches and within the legislative branch itself. Seemingly left out was the judicial branch.

Granted, you have the famous clause from Article VI, Section 2, which, in part, says that rulings by the Supreme Court, "... shall be the Supreme Law of the Land; and Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of the State to the Contrary notwithstanding." This clause clearly gives the Supreme Court dominance over State courts, but says nothing about laws enacted by Congress. Article III gives the Court the authority to decide cases arising under the Constitution; again, no direct mention of Congress; but we are getting a bit closer. There are other clauses in the Constitution as well that refer to specific requirements for an act to be a Crime, such as the need for more than one witness to establish Treason and Article 1 prohibits States from imposing an export tax; again, bits and pieces, but no nexus between Congress and the Judicial Branch.

Moreover, the physical environment given the Supreme Court and its lower appellate courts belied the apparent low esteem this branch was to be held in. They had no office of their own, they had to borrow from the Senate; the justices, yes, the Supreme Court justices, rode a circuit, hearing cases around the nation; not that it made any difference. It was problematic that a State would listen to their ruling, let alone abide by it. This state of affairs was just fine with fiscal/political conservatives such as Thomas Jefferson, but it stuck in the craw of such liberals as John Adams and Alexander Hamilton and remained the case until John Adams and the Federalists, (the liberals of the day, much like today's Democrats) who managed to get the Constitution ratified, won control of government.

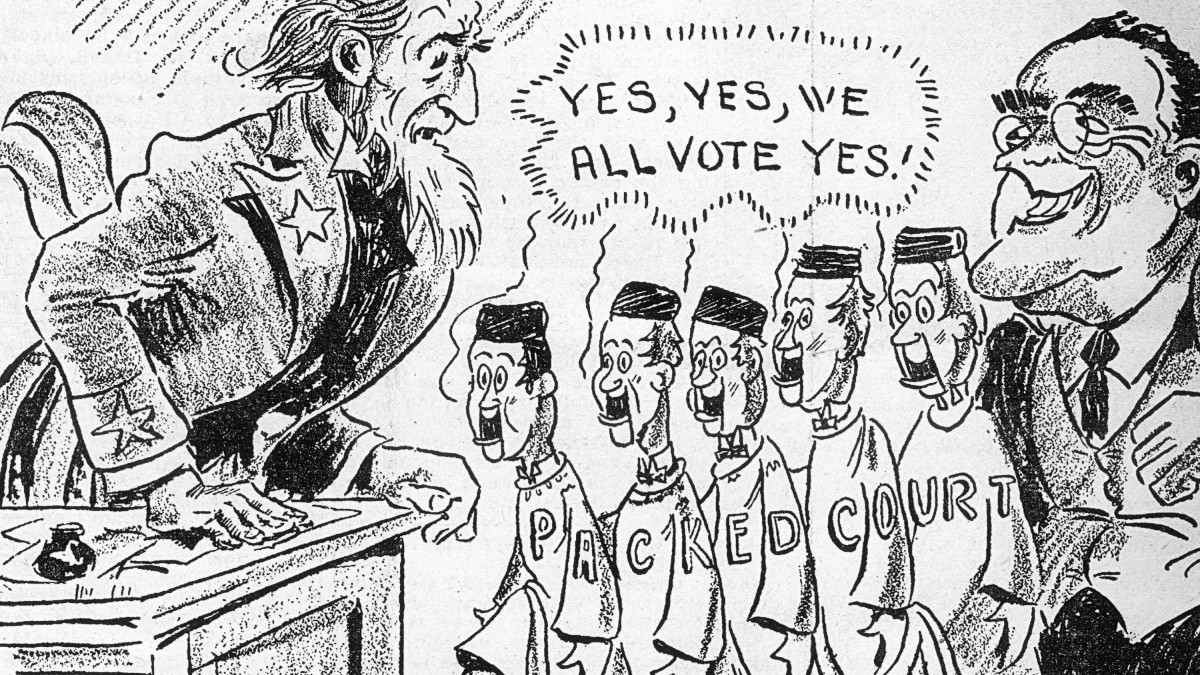

Things changed rapidly for the Supreme Court. One such improvement, from the Courts point of view anyway, was the Judiciary Act passed by the Federalist Congress. It, among other things, changed the number of justices from 6 to 5, expanded the federal courts authority, increased the number of lower courts, and got rid of the requirement for the justices to ride a circuit*. This act was an overt move by the Federalists to protect their turf when the conservative Democratic Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, assumed power in 1801.

Conservatives of the 1800s, like the Conservatives of the 2000s, dislike and distrust the judicial branch very much. Thomas Jefferson said,

"... each of the three departments has equally the right to decide for itself what is its duties under the constitution, without any regard to what the others may have decided for themselves under a similar question."*

In other words, it would seem President Jefferson believes that the U.S. Constitution does not, nor did it intend to provide for any checks and balances between the branches beyond those specifically written into the Constitution, such as the Advice and Consent clause. As a moderate, this is an astounding and counter-intuitive statement. In any case, when he and the Democratic Republicans swept the presidency and Congress, they set about trying to undo all that the Federalists had done in giving the judicial branch and the Supreme Court more legitimacy, authority, and power*. (Keep in mind, it was the Federalists who supported the ratification of the Constitution and what became the Democratic Republican party who opposed such ratification! Also, in today's parlance, the Federalists are Democrats and the Democratic Republicans are Tea Party/Conservatives.)

Not to be outdone in pure politics, the Conservatives repealed parts of the Judiciary Act, an understandable move, but then went further. One of the provisions of the Judiciary Act was to increase the number of lower court judgeship's which allowed the lame-duck President John Adams to make sixteen last minute appointments. Clearly, conservatives did not want liberal judges in the federal government, so they set about trying to impeach them!* This, of course, action was on shaky Constitutional grounds, but hey, no problem, the Democrat Republicans simply didn't let the Supreme Court meet until 1803 to consider its merits.* They were successful in impeaching Judge John Pickering, but unsuccessful in doing the same to Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. I am not totally sure how successful the Jeffersonians were in their purge, but the late night appointments by President Adams, and the Democratic Republicans desire to reverse them set the stage for what I believe to be the most significant decision ever handed down by the Supreme Court!

THE MAN AND THE RULING THAT CHANGED AMERICA

THE RUN-UP TO MARBURY v. MADISON

WILLIAM MARBURY WAS A JUDICIAL APPOINTEE by President John Adams on the evening of March 3, 1801. Adams' appointed him Justice of the Peace of the District of Columbia the night before Thomas Jefferson was to be sworn in as President; Marbury was one of the "midnight judges" which resulted from the Judiciary Act of 1801. The appropriate paperword was prepared and given to Secratary of State John Marshall, soon to become Chief Justice John Marshall, who affixed the great seal to Marbury's commission; it was never delivered to Marbury before Jefferson became president and now President Jefferson found it and chose to not to deliver it to Mr. Marbury.*

Those are the simple facts to what was going to become one of the most complex cases the Court was ever to face and which pitted two philosophies, which are polar opposites, against each other. These facts were never in doubt, nor what subsequently happened. Marbury wanted his commission, so he wrote Secratary of State James Madison to provide it to him as the law requires, and was ignored. As a result, Marbury decided to sue for the delivery of the commission into his possession.*

The problem William Marbury faced was where to bring the suit. The state courts were not the solution, since this was a purely federal matter, and, in any case, the Democratic Republicans were in the process of "purging" Federalist judges from the state ranks. Suing in the newly created federal court in the District of Columbia was problematic as well. The chief judge there was now a Democratic Republican, and, in any event, the Conservative Congress only left a small scope of cases that could be raised in the District; there is also the possibility that if Marbury brought suit there, the Congress would simply abolish the court under him.*

That left only one alternative, the Supreme Court, but, under what theory? Marbury discovered a federal statute that said that the Supreme Court may issue a writ of mandamus, which compels an officeholder to perform a routine task, to any court or persons holding an office constituted under the authority of the United States. Perfect. James Madison was an officeholder of an office duly constituted under the authority of the United States and the delivery of his commission, a mere formality but still necessary for Marbury to authenticate his status as a Justice of the Peace, is such a routine task. Consequently, William Marbury brought the case directly to the Supreme Court in order to obtain the writ which would compel James Madison to deliver hum his commission ... or so he thought.

ON THE HORNS OF A DELIMMA

NOTHING, THEY SAY, IS AS EASY AS IT SEEMS, the old saying goes and this old saw may have been born from Marbury v. Madison. The problem was started by President Jefferson who told Secretary of State Madison to simply ignore the Supreme Court's proceedings, simply do not respond!! You see, Jefferson, as most conservatives, even today, didn't believe the Court had the power to review the constitutionality of federal law. Nor did he believe the Court had jurisdiction over his own actions, as President, in refusing to deliver the commission, so, from his point of view, it is best to pretend this case isn't even happening. (Can you imagine that happening today?)

This approach left the Court in a bit of a sticky-wicket. On the one hand, they could bend to Jefferson and rule the law, in fact, does not entitle Marbury to his commission; and in the process confirm and solidify for eternity the weakness of the judicial branch in general, and the Supreme Court, in particular. It would also tend to validate the idea that the courts, and perhaps the law itself* could not stand in the way of a determined President. That route was not an acceptable outcome to John Marshall, now the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

On the other hand, the Court could find for William Marbury and rule that yes, indeed, the President and James Madison must deliver the commission to him. But, what if President Jefferson simply ignored their ruling, as many conservatives believed should be the case anyway, and continued to refuse to deliver the commission to Marbury? The Court had no mechanism with which to enforce their own order and face what Justice Breyer, in his book, pointed out as the Hotspur question, to wit:

Owen Glendower, of Shakespere's Henry IV, boasts "I can call the spirits from the very deep", to which Hotspur replies, "Why, so can I, so can any man, but will they come when you do call for them?"

This, of course, was not an acceptable solution either for Chief Justice Marshall. The Court can neither find in favor of Marbury or rule against him, so what to do?

THE ANSWER IS A CAREFUL READING OF THE LAW AND AN AGILE MIND

AS HISTORY SHOWS, MARSHALL found a way out of his delimma, and it was absolutely elegant; the conservatives won their battle, but the liberals won the war. C

The question before the Court is "Should the Court issue a writ of mandamus ordering the secretary of state to complete a routine, ministerial action and deliver the commission to William Marbury?" (You will see why I underlined "should" in a bit.) Clearly, the law says Marbury is entitled to a copy of the commission as well as the secretary of state has a legal duty to deliver it; that, as far as Marshall is concerned are statements of fact.

Now the question is, given that Marbury has a legal right to the commission, does he have a way to legally enforce the delivery. In this case he did, via the writ of mandamus, which falls in line with the philosophy that if there is a legal right, there must be a legal remedy. And, as Justice Breyer points out the "very essence of civil liberty consists of the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives and injury"; although there are some exceptions like for "political acts" of the president. Now the question revolves around whether the actions of the president were bound by law or purely discretionary. In Marbury's case, his right to his commission is a matter of law, not presidential discretion.

Even though Marshall has shown that Marbury has the legal right to the commission and a way to a legal remedy, the next question that must be considered is President Jefferson's question, "Does the Court have the right to rule in this case?" Does the Court have the power to grant Marbury a writ of mandamus? The answer to this question must also be "yes" because it is a federal statute that gives the Supreme Court the specific ability to issue such a writ in this case; consequently, the Court does have proper jurisdiction.

The answer seems perfectly clear, but as the famous TV saying goes, "But Wait, There's More!"; and Chief Justice Marshall had one more thing to consider ... "Did Congress have the authority to write such federal statute in the first place?"

Here is where my "Should" now becomes a "Could" in the first question Marshall considered. The answer to this critical question, as most in the U.S. know, "No", Congress did not have the authority to pass such a statute giving the Supreme Court such authority. And why not you (and conservatives) ask?

Because the federal statute Marbury is using as his legal remedy conflicts with the U.S. Constitution, and thus begins the reasoning behind the principle of "Judicial Review". The part of the Constitution Chief Justice Marshall is relying on, in this case, is Article III, Section 2, Clause 2, which states,

"In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make."

So, here is the problem the Court is now facing, did the federal statute give the Court "original" jurisdiction and, if so, was it in conflict with Article III, Section 2, Clause 3? Clearly it did both. And, now we are down to our final two, and most historic questions ever to face the Supreme Court or the Congress of the United States,

"does the Supreme Court have jurisdiction to make the following determination?"

and

"whether an act repugnant to the constitution can become law of the land"

So, on what basis did the Court support its decision that it had jurisdiction? Again, Article III was referred to, this time Section 2, Clause 1, which states, in part,

"The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;—"

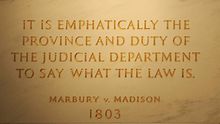

Clearly, Marbury v. Madison had now devolved down to a case of conflicting federal laws, on the one hand, the federal statute which Marbury is relying on which gives the Court original jurisdiction, and on the other, the constitution (a law) which says the Court only has appellate jurisdiction over this kind of statute. And, because of Article 1, Section 2, Clause 1, plus several other supporting argument, the Supreme Court concluded it did have the right to review laws passed by Congress which might conflict with the constitution; in other words, Chief Justice John Marshall reasoned, the Supreme Court, based on the U.S. Constitution, did have the duty of Judicial Review.

AFTERWARD

THE COURT HELD that the statutory authority Congress granted the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus was unconstitutional and therefore void. As a consequence, the Court could not hear Marbury's case as a matter of original jurisdiction, therefore James Madison, and therefore President Jefferson won the battle, they didn't have to, at least at this point in time, give Marbury his copy of the commission as the law required them to do; Marbury would have to file in a lower court first. But, in doing in winning the battle, they lost the war, for in order to give President Jefferson what he wanted, Chief Justice John Marshall established one of the great checks on Congressional power, Judicial Review, that is a consequence of the thinking of the founders who wrote such an incredible document as the United States Constitution.

© 2012 Scott Belford