The Shipwreck Appeal

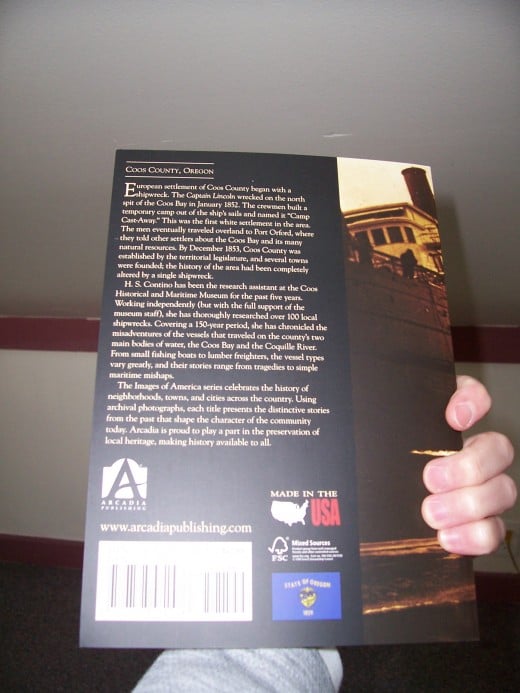

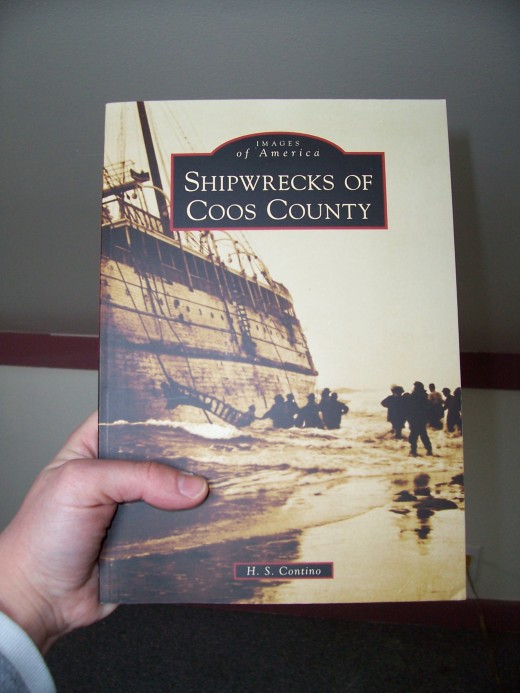

A few months ago, I published my first book, "Shipwrecks of Coos County". The book provides a photographic overview of local shipwrecks. It focuses on the two main bodies of water in Coos County, Oregon, which are the Coos Bay and the Coquille River. The final chapter of the book discusses coastal wrecks. I realize that my opinion on the matter is completely biased, but I think that the book turned out beautifully. It’s only been on the market for a few months, but it seems to be selling well—especially for a first book, and one that focuses on a particular geographical area. However, in the past few months, I’ve been asked the same question regarding the book so many times that I’ve lost count: “Why shipwrecks?”

It seems that people are baffled by why I chose to research and write about shipwrecks—which tends to be a very male dominated topic. In fact, during my research, I found very few books or articles that were written about the topic by women . So, I figured that I’d take a few minutes to try to explain my interest in shipwrecks.

Fascinating Stories

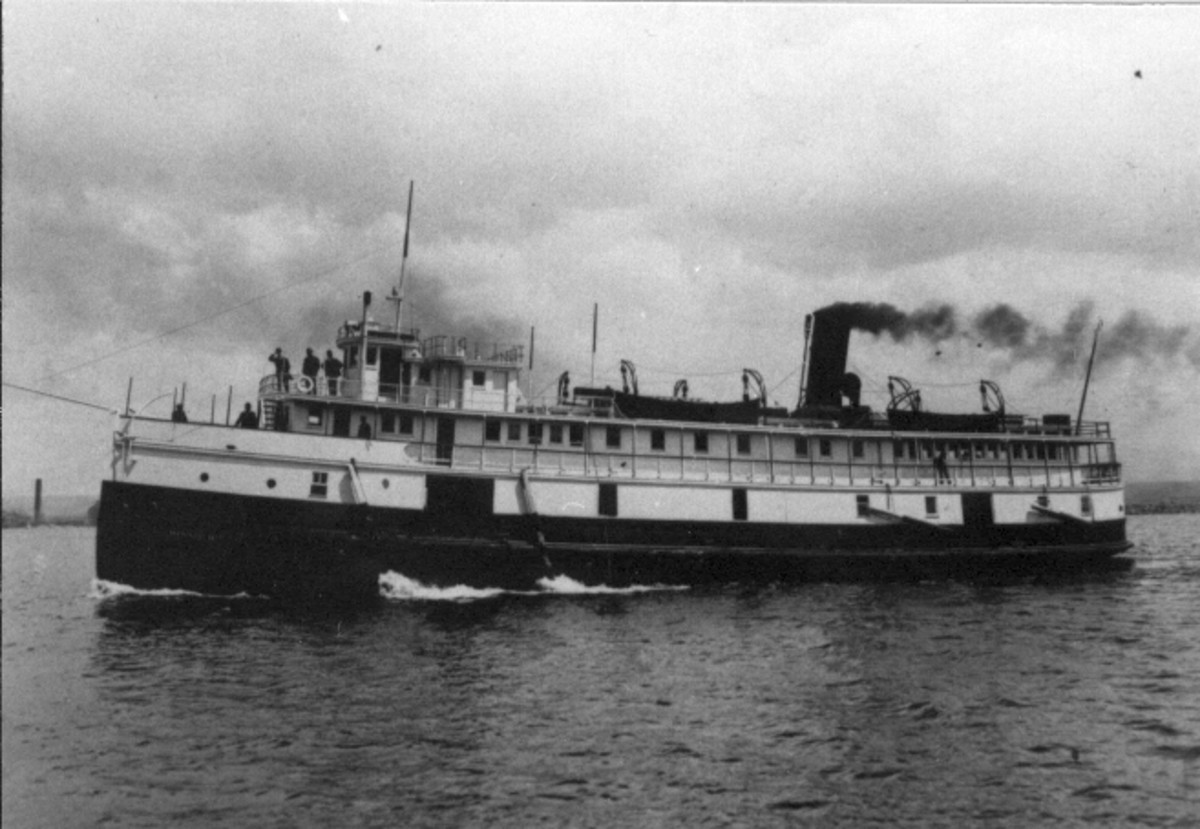

First and foremost, shipwrecks make fascinating stories. In a sense, they’re like mystery stories. By investigating the wrecks, interviewing survivors and witnesses, etc. we’re given the opportunity to put the pieces of the puzzle together. What went wrong? Why did the ship sink? Was it salvageable? Were the passengers and crew rescued?

The Human Element

When you read about shipwrecks, it’s important to remember that they’re not just stories about ships. They’re also the stories of the many people involved—the passengers, crew, and spectators. In each incident, a group of people is placed in a high stress, dangerous, and potentially deadly situation. It’s interesting to see how they react. Shipwreck stories are full of both heroes and villains.

It Takes One to Know One

I had one friend joke that shipwrecks appeal to me because “it takes one to know one.” Well, rather than look at my life as a series of disasters, I’d like to view it as “a work in progress.” I’d like to compare myself to the schooner North Bend . After the ship grounded on Peacock Spit (near the Columbia River) in January 1928, all attempts to pull the vessel off of the sand failed. The ship was stripped of anything valuable and abandoned. Over the next year or so, the ship—with the aid of high tides, wind, and storms—slowly worked itself across the sand spit (approximately 1200 feet) and successfully refloated herself in Baker’s Bay. Henceforth, she was given the nickname “the ship that walked.”

So, wreck or not, I’d like to think that my story will work itself out in the end.J