The Relationship between Science and Religion in the 17th Century - Part 1

Galileo Galilei’s contributions to astronomy, mathematics and science are irrefutable. However, in the seventeenth century, his hypotheses caused friction with the Catholic Church, culminating in his being forced to recant his views and placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life. Beginning with the statements of Nicholas Cusanus and reinforced by the research of Nicholas Copernicus, a discord between the Church and natural sciences began to appear. Prior to that there was little question of the authority of the Church in relation to its authority in the sciences. Galileo was a staunch Catholic, but his views were meant to separate the views of Scripture and that of natural science in relation to what the intended outcome of both views were expected to be. This caused a schism between the theology of the Church and what scientific theories should be baselined against. Even with his eventual trial and abjuration by the Holy Roman Church, Galileo’s theories that supported a heliocentric universe had pushed the biblical views of science, of the Churches literal interpretation of the Bible to the limit and set the course for future thinkers and how natural science would evolve in light of the heavy hand of the Catholic Church.

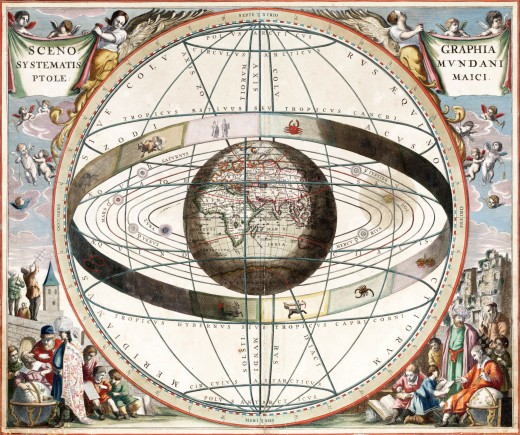

In order to understand the differences between the natural sciences and religion, specifically the Catholic Churches view, during the time of Galileo, an understanding of the system of thought that served as the background for the Churches position, and therefore, everyone’s position, is required. In this “old world scheme”[1] Aristotle is the central focus. His view, that everything in the universe lay in plain contrast and that of natural place, stands to reason that there is a center, and that “certain things whose nature it is always to move away from the centre (sic), and others always towards the centre.”[2] The heavenly realms would continue eternal while the things of Earth would remain transitory. This then leads to his theory that all natural bodies are made up of one of four elements, earth, water, air and fire, and that these four elements dictate their natural place; earth and water being heavier have the tendency to move down towards the center while the lighter air and fire have the tendency to move away from the center. By his reasoning, the Earth (made of the earth element) remains stable, at the center of all things and in its natural place, the Sun (the fire element) would move away from the center. But of equal importance, is the position of the Church that even attempting to gain knowledge of nature through Scripture was not the focus. The focus was salvation. Saint Augustine even admonished his listeners who were seeking natural knowledge rather than issues of salvation. He stated that, “There is a great deal of subtle and learned inquiry into these questions [nature]... but I have no further time to go into these questions and discuss them, nor should they have time whom I wish to see instructed for their salvation.”[3] This is the backdrop that formed the framework for the Catholic Church’s geocentric biblical viewpoint.

[1] John Charleton Hardwick, Religion and Science: From Galileo to Bergson (New York: The MacMillan Co., 1920), Kindle Edition.

[2] Giora Hon and Bernard R. Goldstein, "What Keeps the Earth in Its Place? The Concept of Stability in Plato and Aristotle." Centaurus 50, no. 4 (2008), 309.

[3] George V. Coyne, "Science Meets Biblical Exegesis in the Galileo Affair." Zygon: Journal of Religion & Science (2013), 223.

John Hardwick posits that during the Middle Ages, there was a religious harmony with natural science, this being due to imperfect knowledge that, as time marches forward, has little chance of repeating itself, “having tasted of the fruits of knowledge, the human race is cast forth from its Paradise.”[1] The Catholic Church was comfortable in its geocentric view. The Aristotelian view clearly made sense and was easily adapted to Scripture. Aristotle’s view could be lined up with passages of Scripture, such as Joshua 10:12-13 and Psalm 93:1, both seemingly clear that the Sun moves, not the Earth. It must be noted, however, that this view was not always the position of the entire Church. According to Michael Shanks, there are examples of Aristotle’s views of natural philosophy that were forbidden in Paris in 1210 and 1215 and that while “churchmen acting in their official capacities did issue these condemnations, it is misleading to say that “the Church” did so, for this seems to imply that they were valid for all of Christendom.”[2] This view is added to by Professor Mauricio Nieto, who states that men with marked spirituality such as

Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Boyle, Bacon, Descartes, all the heroes of that supposed scientific revolution, were profoundly religious and in most cases their works are rendered meaningless without their theological conceptions of the universe.[3]

[1] Hardwick, Religion and Science: From Galileo to Bergson, Kindle Edition.

[2] Ronald L. Numbers, Galileo Goes To Jail And Other Myths About Science And Religion. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 24.

[3] Mauricio Nieto, interview by Franklin Gamwell. Rethinking the Relation between Science and Religion: Some Epistemological and Political Implications (January 1, 2015), 259.

But one of the common mistakes man makes is to take Scripture out of context. For example, following Joshua’s statement in verses 12 and 13. But by leaving out verse 14, it’s easy to see how the Church could form a basis for a geocentric viewpoint. But in context Joshua is letting it be known that the Sun and Moon stopped only on that day, through the intervention of God, but that there never will be another day like it. It was a one-time occurrence, not a basis for a geocentric view. But many in the Church disagreed. Cardinal Robert Bellarmine and John Calvin were two such people who believed that the Bible plainly proved that the Earth is immovable and at the center supporting the Aristotelian view and that there was no “true demonstration that the sun was in the center of the universe and the earth in the third sphere, and that the sun did not travel around the earth but the earth circled the sun…”[1]

[1] Bellarmine, Robert. "Modern History Sourcebook: Letter on Galileo's Theories, 1615" Fordham University. (January 1999), http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1615bellarmine-letter.asp.

In 1440, German Cardinal Nicholas of Cusanus, a self-taught theologian and philosopher, wrote “De docta ignorantia: On Learned Ignorance” that addressed what were considered the four traditional realities of Christian thought, that of God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings. Clyde Lee Miller points out that Cusanus believed that,

…the natural universe is characterized by change or motion; it is not static in time and space. But finite change and motion, ontologically speaking, are also matters of more and less and have no fixed maximum or minimum.[1]

This unconventional idea, that there is no point in the universe that can be considered the center, but that man, regardless of his location be it on Earth, the Sun, or star, will always regard himself as being at the center of existence. This completely denies the Aristotelian view held by the Church. Cusanus makes the comparison by stating that, “We are like a man in a boat sailing with the stream, who does not know that the water is flowing, and who cannot see the banks; how is he to discover whether the boat is moving?”[2] This caused a disruption in the whole geocentric position and would only fuel the fire of what was yet to come, namely, Nicholas Copernicus.

[1] Miller, Clyde Lee. "Cusanus, Nicolaus [Nicolas of Cusa]." The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (July 10, 2009), accessed October 1, 2015, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cusanus/.

[2] Hardwick, Religion and Science: From Galileo to Bergson, Kindle Edition