Quintessentially Provence?

Ask anyone what image springs to mind when they think of Provence, and these features are sure to be among the answers: rolling lavender fields, glorious winter mimosa, olive groves, citrus trees, hill-top villages, cheery terracotta pots full of geraniums, bustling markets, an easy-going pace of life and lazy lunches washed down with chilled bottles of rosé wine. Yet Provence is a huge area – over 25,000 square kilometres in all – and boasts such a wide variety of topographical features and microclimates, that can any one element really be considered quintessentially Provencal?

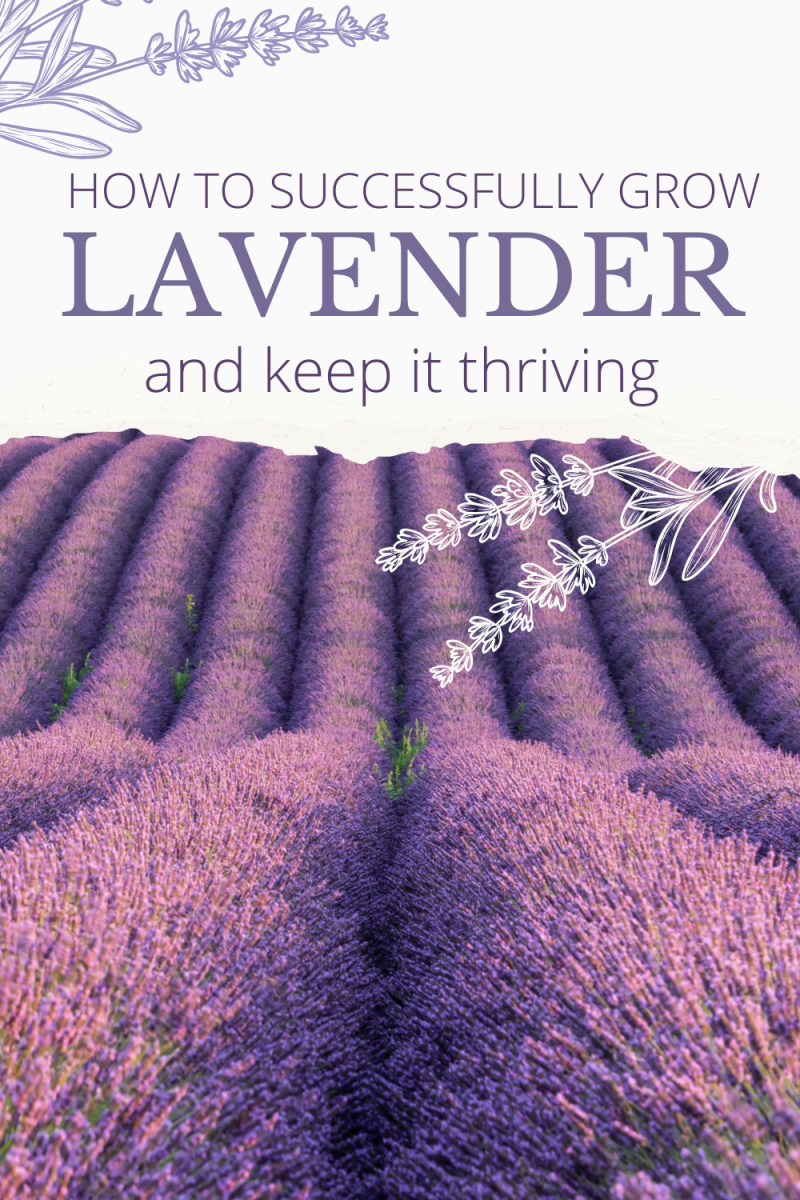

Lavender - the defining symbol of Provence?

Let’s start with lavender, surely a defining symbol of Provence. While lavender grows in abundance all over the region, being hardy and self-seeding, the picturesque rolling fields so often photographed in guidebooks are mostly to be found up in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, stretching from the pre-Alps near Gigne to the Valensole plateau, the most important lavender-producing area in France. True lavender (lavandula angustifolia) grows best at an altitude of 600 - 1,600 metres above sea level, while Spike lavender (lavandula latifolia) prefers higher temperatures and lower altitudes of between 200 – 500 metres. The favourite of many Provencal gardens is, in fact, a cross between the two.

Mimosa - a splash of winter colour

While lavender is indeed a native of the Mediterranean, the same cannot be said for that other south of France favourite, the mimosa. Related to the Acacia family, the mimosa was introduced to the region from Australia in the eighteenth century by British explorer Captain James Cook. It was an instant hit and, given the mild and sunny climate, quickly took root, making much of Provence its home. There are hundreds of varieties, some of which have even adapted to the sandier soils of Cannes and Golfe-Juan, but it is in the Var where mimosas are most abundant, to the extent that the departement boasts its very own 130 km long mimosa trail, starting in Bormes-les-mimosas and winding its way through to Grasse, where the flowers are used in perfumes.

The ancient olive

If mimosas are relative upstarts in the region, olive trees have been around for, quite literally, thousands of years, with olive groves spanning Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. In Provence, it is in the Alpilles area of the Bouche-du-Rhone, or more specifically, the Les Baux valley, that is said to produce the most outstanding of olives and oils, with a flavour reminiscent of dried fruits and almonds. Without olive oil, Provence would lose many of its culinary specialities, such as aioli , tapenade and soupe au pistou . The less acid olive oil contains, the better it is. Of course no two olive oils are the same, and the intensity of flavour varies depending on the region. In general, chefs prefer the pronounced flavours of a newly-pressed olive oil for vegetables and sauces, a lighter one for salads and a more strongly-flavoured one for fish and pasta.

Citrus trees and the warmth of the south

Like the olive, citrus trees symbolise the warmth of the south, with the Mediterranean climate being ideal for their cultivation – in pots as well as in open ground. Lemons were introduced to the region by the Romans, and flourished particularly well in the calcareous soils and the microclimate of Menton, in the Alpes-Maritimes. The lemon and its companion, the orange, took over the surrounding hillsides, and flourished so successfully that by 1929 Menton had become Europe’s largest producer of lemons, with some 100,000 trees. Cultivation has subsequently diminished, but the annual lemon festival – a staple of the Provencal calendar – serves to remind us of Menton’s citrus heritage. Beyond the Alps-Maritimes, however, citrus trees don’t fare so well. Although easily adaptable, they require a good deal of sun, and, in particular, shelter from the wind – making the areas on the receiving end of the Mistral largely unsuitable.

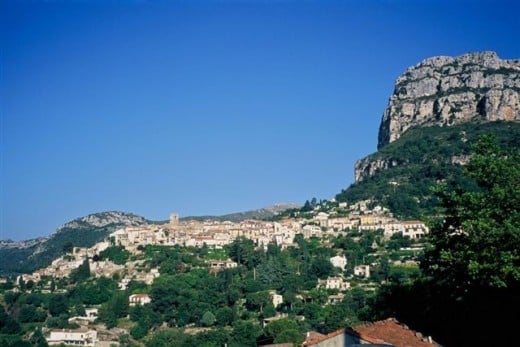

Pretty hill-top villages

Hill-top, or perched, villages are another Provencal mainstay. Historically the coastline was always exposed to attack, so villages were built on the tops of hills, perhaps adding walls to produce an impregnable fortress. Many of Provence’s most delightful hill villages are to be found in the Alpes-Maritimes and the Var. St Jeannet, photographed here, provided the backdrop to the Grace Kelly/Cary Grant caper, To Catch A Thief.

Other hubs you might enjoy:

- Ten Outstanding Restaurants on the French Riviera

A look at ten of the most outstanding restaurants on the French Riviera, and how you don't have to spend a fortune to enjoy an incredible gastronomic experience. - Shoptastic Riviera!

An overview of the kinds of things you might like to buy during a visit to the French Riviera. - The French Riviera on a Budget

Summer is upon us, and the French Riviera is once again chock-a-block full of celebrities, movie stars, supermodels and Paris Hilton. The Beckhams are tucked away in their mansion in Bargemon, and I dare say...

Succulents make sense

One of the joys of wandering around medieval villages are the terracotta pots filled with geraniums, which make a lively splash of colour throughout summer, but in the Alpes-Maritimes, where water can be at a premium, the canny year-round gardener knows to fill pots and rocky borders with drought-resistant succulents, creating a more exotic effect.

- Succulents: the plants of the future?

When I first moved from London to the south of France, I was thrilled to find an apartment with a large, wrap-around terrace that basked in full sun all day. One of my earliest shopping trips was to the...

- Rural French Life: The Brocante

Twice a year, every year, my little village in the south of France holds a brocante, less romantically known in English as a car boot sale. For the sellers, its a chance to clear out the attic,...

Provencal markets

Another of the greatest joys of visiting Provence is its markets, and Toulon’s in particular – said to have inspired the Gilbert Bécaud song “Les Marchés de Provence” – stands out. With stalls full of fresh fruit and vegetables, such as asparagus, artichokes, tomatoes, bell peppers, aubergines, courgettes, pumpkins, pink sweet onions and mesclun – the mix of young salad shoots – not to mention the variety of olives – either marinated in herbs, stuffed with anchovies or crushed in a fennel broth – there’s seemingly no end to the choice on offer.

Long lazy lunches

Which of course brings us on to those idyllic lunches, shared under the shade of an olive tree or a vine-covered terrace. Who can resist the idea of sun-ripened Provencal vegetables, fresh aromatic herbs and drizzles of olive oil? The best vegetables are said to come from the Vaucluse, a particularly fertile region. Tomatoes, aubergines, bell peppers and courgettes are of course the main ingredients of ratatouille, the popular vegetable stew, so what could be more quintessentially Provencal? But tomatoes, surprisingly enough, are a relative newcomer to the region, introduced from South America during the 16th century by the Spanish. In fact, if it weren’t for the Spanish, ratatouille might not exist at all, because the bell pepper and the courgette also originate from South America. The aubergine, by contrast, is a native of India, and thought to have been brought across by Arabs in the middle ages. Typical Provencal vegetables might not actually be native to the region, but many would agree that Provencal cooking has created some of the most memorable dishes using them.

Arab influences

That said, one of Provence’s culinary mainstays – les petits farcis – where any of the above-mentioned vegetables are hollowed out and stuffed with meat, cheese, vegetables, herbs or spices – actually owes its roots to Arab invaders. Likewise, there are Arab influences throughout much traditional Provencal cuisine, such as using spices and dried orange peel in stews, not to mention chickpea flour, almonds, raisins, pine nuts, cinnamon and saffron.

- The Thirteen Christmas Desserts of Provence

Traditionally in Provence on Christmas Eve you eat thirteen desserts, which represent Jesus and the Apostles. This might seem daunting, but you only need a mouthful or two of each, and most are natural and healthy.

Delicious rosé wines

One indisputable feature of Provence is its rosé wine, fondly quaffed by tourists and locals alike, but often derided by connoisseurs for being neither one thing nor the other. In fact, rosé is the ancestor of all wines – the custom until the Middle Ages being to separate the grapes’ skin, responsible for the colour, from the juice at an early stage in wine production, making the resulting wine pink, or at least pale. Drinking habits and colour preferences may have changed over the years, but Provence has stayed true to its rosé tradition. Rosé counts for around 70 per cent of production in Cotes de Provence wines, and, drunk as an aperatif, is the ideal partner for canapés and olives, and is said to arouse the appetite for the wines to come. However, as it goes so well with most Provencal dishes, it is no longer considered a holiday indulgence, and may be enjoyed all year round.

The charms of Provence

The produce and charms of Provence, so diverse yet complimentary, despite their varied geographical origins, will doubtless continue to conjure up romantic images for years to come. Even if many of its so-called “typical” elements were, in fact, introduced to the region by others, it is in Provence where everything combines to make a glorious, desirable whole. As gourmet chef Robert Carrier puts it in his book Feasts of Provence: “Provence is more than a geographical entity, it’s a state of mind”.