Visiting College Green, in Dublin, Ireland: the old Parliament and the old University at the centre

Set in stone, telling a long story

I think College Green (Irish: Faiche an Choláiste ) in Ireland's capital, Dublin (Irish: Baile Átha Cliath ) is a very special spot. It is where two remarkable buildings are situated. Both buildings of which I write are architecturally outstanding. Both are deeply historical.

The Irish Houses of Parliament

When the onlooker passes the massive frontage of what is now part of the Bank of Ireland (Banc na hÉireann ) he or she might at first think, Well, it's the headquarters of Ireland's national bank. Well, it isn't; the Central Bank of Ireland (Banc Ceannais na hÉireann ) is actually housed in a different building not far away. Instead, the Bank of Ireland building at College Green — a magnificent, pillared structure — was acquired commercially in 1803, and the company has used it ever since. The previous landlords of this monumental 18th century buidling were the Irish Houses of Parliament (Irish: Tithe na Parlaiminte ), which — under persuasion — ceased to exist in 1801, when the 1800 Act of Union came into effect. Previously, this separate British Parliament existed under the Crown, with historical figures such as Henry Grattan (1746-1820) being prominent; indeed, Grattan argued strongly against the Irish Parliament's abolition. (It is interesting that only in the past few years have some of the provisions of the 1800 Act of Union, as they affected Northern Ireland, been repealed.) It should be noted also that the current Irish legislature (Irish: Oireachtas Éireann ) is based in Leinster House (Irish: Teach Laighean ) and not in these former Parliament buildings. (Historical note: Following the provisions of the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, a few representatives tried to set up another [southern] Irish Parliament housed over the other side of College Green at Trinity College, but by then the upheavals of the Sinn Féin -related Easter Rising of 1916 had taken such a firm hold, that this attempt did not meet with success.)

One of the architects of the former Parliament of Ireland buildings was James Gandon (1742-1823), responsible for a significant examples of fine architecture in Dublin from an era when Georgian style was particularly in vogue.

And, oh, (just to mention it) the Parliamentary history of the College Green area did not begin with this former institution under British auspices: go back a thousand-odd years and the Vikings used to hold quasi-legislative sessions of their Thing not far from here.

Trinity College

From a massive Parliament building, which doesn't house a Parliament, cross College Green to a University, which consists of one college, Trinity College (Irish: Coláiste na Tríonóide ). Actually, this state of affairs in some ways approximates American usage of the terms 'university' and 'college', which in some cases can be more fluid and interchangeable than would usually be the case in the British Isles. Although for years — centuries, even — there have been law suits and debates to try to establish what is the difference between the University of Dublin and Trinity College, no-one really seems to be able to prove conclusively whether there is a tangible distinction.

The 1759 built College Green Front Arch entrance of Trinity College is thought to have been designed by Theodore Jacobsen. (I say, 'thought to have been', because previously it was assumed that someone else did.) The college itself was founded in 1592, and among the many exhibits of its famous Library is the illuminated Book of Kells (Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais ), dated c. 800, housed in the Long Room. (For a number of years, I used to receive the journal of Trinity College Library, which is also called The Long Room. ) Going through the Front Arch entrance, the very large courtyard area is known as Parliament Square (interesting name...), with the Campanile structure in the middle. The oldest existing buidlings at Trinity College are the Rubrics, built about 1700.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, in theory, Trinity College was open to students of the Roman Catholic faith. Until 1970 when Archbishop McQuaid lifted the ban, any Roman Catholic student attending Trinity College without special permission was under the threat of possible sanction or, theoretically, even excommunication. In practice, relatively few non-Protestants attended the institution. Years later, former President of Ireland (Irish: An t'Uachtarán na hÉireann ) Mary Robinson was elected the University of Dublin's Chancellor (Irish: Seansailéir Ollscoil Átha Cliath ).

College Green is the spot where Charles Haughey, later Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) famously burned a British Union flag in 1945.

So — on that note — wherever else you choose to visit in Dublin (and there is plenty else to see) make sure that you stop by this remarkable, historic spot: College Green.

Also worth seeing

Dublin's visitor attractions of architectural merit and historic import are too numerous to mention here, but a fraction of these include the following:

Dublin Castle (Irish: Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath ; distance: 1.1 kilometres), the origins of which go back about 1000 years, was for centuries the hub of British rule in Ireland, and is today the venue for the inauguration of the President of Ireland.

Four Courts (Irish: Na Ceithre Cúirteanna ; distance: 2.1 kilometres), overlooking the Liffey River (Irish: An Life ), house, as the name implies, most of the Republic's main courts.

The General Post Office (Irish: Ard-Oifig an Phoist ; distance: c. 0.7 kilometres) on O'Connell Street (Irish: Sráid Uí Chonaill ), the scene of the 1916 Easter Rising (Irish: Éirí Amach na Cásca ).

Custom House (Irish: Teach an Chustaim ; distance: 1.2 kilometres), this fine 18th century building overlooking the Liffey River was the scene of conflict in the Irish War of Independence, in 1921.

Leinster House (Irish: Teach Laighean ; distance: c. 1.3 kilometres), an 18th century ducal building, is where the Irish legislature, Oireachtas Éireann , is housed.

Government Buildings (Irish: Tithe an Rialtais ; distance: 1.8 kilometres), first opened in 1911, they house the Taoiseach 's, and other, Departments. Close nearby is Merrion Square (Irish: Cearnóg Mhuirfean ), with many examples of Georgian doorways.

...

How to get there: Aer Lingus flies from New York and Boston to Dublin Airport (Irish: Aerfort Bhaile Átha Cliath ), from where car rental is available. Car parking can be difficult in Dublin City centre and a good way to get around the city is by Dublin Bus (Irish: Bus Átha Cliath ) Please check with the airline or your travel agent for up to date information.

MJFenn is an independent travel writer based in Ontario, Canada.

Other of my hubpages may be of interest

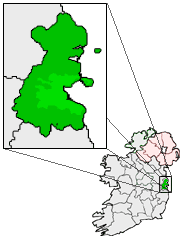

- Visiting Longford, Ireland: where three historic provinces meet

The name Longford, Ireland, refers to both a county in the Irish Midlands and to a town, which is the administrative capital of the country. Longford itself is in the historic province of Leinster, while... - Visiting Cuilcagh, and western Co. Cavan: hillwalking country in Ireland

I used Swanlinbar (Irish: An Muileann Iarainn) as a base for walking to Cuilcagh mountain, situated in County Cavan (Irish: Contae an Chabhin) in north-west Ireland. A little geography It may be noted... - Visiting Cobh, Ireland: picturesque harbour town with a tragic past

This town, on Cork Harbour, can cause deep impressions on the visitor. Indeed, the prospect of the town, with its spire of St. Colman's Cathedral (Irish: Ard Eaglais Naomh Colmn ), seen from the... - Visiting Clones, Ireland: attractive town in County Monaghan

With its Medieval round tower, picturesque town square known as the Diamond, and ancient ecclesiastical architecture, Clones (Irish: Cluain Eois) is a rewarding place for the historically-minded visitor. The...