Orchids: A History of Sex, Drugs & Lies

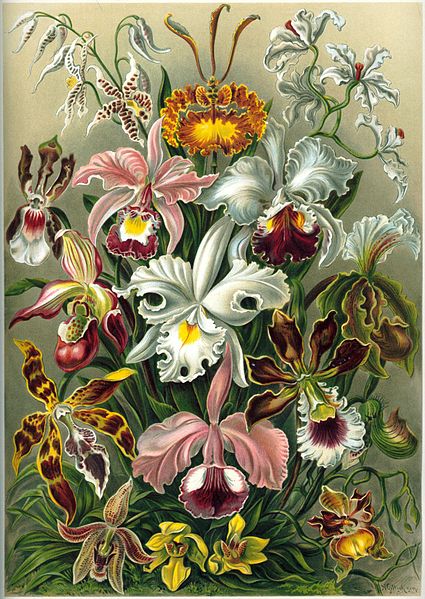

That idyllic image of country field full of flowers in spring where lots of bees and other insects are too busy buzzing around, feeding on the nectar and pollinating the myriads of colourful and scented flowers comes easily to our minds. In fact, most plants reward all types of animals – bats, small mammals, birds, humans and especially insects – for the transport of pollen or seeds that contribute to their dispersion as species. The deal seems fair. However, morality is a human concept and in the world of nature immoral behaving is quite common. There are plants that reach the same result, i. e. spread successfully with the help of animals, but give no reward at all to their animal partners. In fact, some seem to assemble traps and even punish them. This is particularly true and most evident among a particular and most praised group of plants – orchids. Orchids are the biggest family, Orchidaceae, of plant species; more than 25,000 species are known today, from 880 genera and they exist in all continents, except Antarctica. Orchids, in particular, have developed a range of attractive but deceptive strategies that do not provide any kind of reward for the insects that succumb to their irresistible appeal. In this respect and due to their specific specialization in pollinator-plant interaction, orchids are considered the most evolved of all plant species.

Tough Love

Some epiphytes orchids of the genus Oncidium of South America, often popularly called dancing orchids, produce racemes of tiny flowers in clusters endowed with long branches and stalks whose balance is so delicate that at the slightest breeze they dance, hence its popular name. Sharing the same habitat of Oncidium are small bees, whose males are very combative when it comes to defending their territory. This characteristic of the bees is taken advantage of by Oncidium orchids. Their flowers mimic a bee antagonist in perfection, so that the bees literally attack the flowers when they move at the slightest breeze, as if they were rivals usurping their precious territory. The bee does not land on the flower, but merely strikes it, so that the pollinia (mass of pollen grains, singular pollinium) become attached to its head. The pollinia bend downward slightly after they are cemented to the front of the bee’s head, so that they press into the stigma when the bee attacks a second flower. The bees must be accurate to within a millimetre to make the exchange successfully, yet they rarely miss it. In this process and as the bees strike on several “threatening flowers” they end up by both collecting and distributing pollen very much to the Oncidium wishes. Oncidium flowers do not look much like insects, and it is not really clear what in fact makes bees attack them. Yet something about their colour, shape or chemical (possible volatile compounds released by the flower) causes bees to show that aggressive and combative behaviour. The net result is that the Oncidium flowers are cross pollinated, ensuring a mixing of genetic information from generation to generation and thus species propagation.

The orchid, Paphiopedilum rothschildianum, commonly known as the King of Paphs, native from Mount Kinabalu high altitudes in northern Borneo, has two long and twisted wings, stretched horizontally on both sides of its slipper-shaped pouches, which are a modified labellum, or lip, that characterizes the genus. The wing-shaped petals and the lip are green and red spotted which at the eyes of a fly looks like a crowd of aphids. These flies are parasitic flies that prey on aphids to lay their eggs so that their larvae can feed on them. As these parasitic flies do not distinguish real aphids from these colourful spots theyend up by laying their eggs on Paphiopedilum flowers. As they try to lay the eggs, the flies brush against the stigma, part of the flowers female organs, releasing any previously collected pollen from another flower nearby, and then getting some more from the anther, the flowers male organ. This way Paphiopedilum rothschildianum thrives happily and has its job done while the flies parasitic larvae will die eventually as there is nothing from the plant in return to their fooled parents efforts. Although, it seems cruel, the effect of the action of Paphiopedilum on the population of these flies is not that severe as there are plenty of real aphids on the surrounding plants, which are sufficient to ensure the successful reproduction of these flies.

The Art od Deception

European orchids are not able to compete with their tropical relatives when it comes to ostentatious and spectacular beauty. The huge bell-shaped skirts, charming turbans, flickering crowns or elegant flags are not for them. The bee orchids, of the genus Orphis, native from Europe, are a typical example of this European sobriety. They grow up to 50 cm high and produce few flowers on a single spike. The flowers have a trilobed labellum, lip, with two pronounced humps on the hairy lateral lobes; the median lobe is hairy and similar to the abdomen of a bee. It is quite variable in the pattern of coloration, but usually brownish-red with yellow markings. In some species the lateral hairy lobes are very similar to the wings of insects. In fact, the flowers of Orphis apifera orchids are remarkably similar to species of large bees or wasps, common in the Mediterranean region. The role of this mimicry is spectacular and its success even more astounding. Scientists thought that this mimicry was intended to discourage herbivores, like cows, from eating the leaves by giving them the illusion that bees were sitting on the flowers and could sting their tongues eventually.

However, the story although much more intimate and likewise deceptive involves bees only. The flower provokes male solitary bees, of Eucera genus, sexually. Basically, it arouses them. It is much more effective than we could ever imagine, as it also releases a chemical signal, a pheromone, very similar to that emitted by sexually receptive female bees. This can be showed simply by covering one of the orchids with a cloth. Although invisible, it still attracts male bees, which agitated, crawl upon it, looking for the source of this exciting, provocative and irresistible scent. When a male bee finds a flower, it settles onto the flower lip, holding it exactly like if it were a female bee while trying to mate with her. As expected from a healthy and virile male it presses the tip of its abdomen on the fringe of long hairs on the edge of the flower lip. It is obviously doomed to failure, but during this process, and as the male tries to copulate the flower lip, a column bends over the bee and two pollinia patches are glued on the bee head. If the next orchid flower visited by the male bee has already disposed of its pollinia, during the same deceptive process, the column will take possession of the bee patches and the orchid is fertilized. In Europe there are about 40 different species of these orchids, identifiable by its own pattern of identity theft of the insect species that they fool. There are also many natural hybrids. In some Orphis species, notably those that mimic female wasps, the flower lip mimics perfectly a female wasp sexually receptive even in its natural position when it meets the male for mating. In these cases, it’s the male abdomen that gets the pollinia patches which will eventually transfers to another flower. There is also variation among the same species regarding the mimicked female position such that it is possible that the same male bee or male wasp gets two different sets of pollinia patches on the head and on the abdomen. Clearly, here you can say that the orchids thought on every aspect.

These couplings are clearly unsatisfactory for the male wasp or male bee, which quickly learn that they should not rely on such scent that attracts them to such passive partners. Clearly, this can reduce their value as pollinators, as when covered with pollinia, they may not return to visit other orchids and thus deliver such precious goods. However, though the Orphis orchids produce a scent that mimics the female pheromone perfectly, different plants of the same species do not all smell the same. Each plant differs from others with a slightly different fragrance enough to suggest to the male bee or male wasp that visits it that will get the satisfaction that has been deprived of. However, after visiting four or five different plants, the insect learns its lesson that all those “partners” that smell that way are useless and no longer visits them. However, when the insect gets that it is likely it has already done what the orchids wanted.

The victim of the most extraordinary sexual fraud is an Australian wasp whose females prey on beetle larvae. As these live in the soil, feeding on plant roots, the female wasp has to dig the ground in order to find them. In this way, wings are not much of use if one has to spend most of its life digging and living underground searching for food. Thus the female wasp has no wings. Once mature and sexually receptive the female wasp digs her way up to the surface. She climbs up the stem of a plant and releases a pheromone to attract her flying male partner. Once detected the male wasp flies in her direction. But instead of mating right away the male wasp grabs the female and the two fly away. They mate on air. But that is not end. While flying romantically the male visits some flowers and provides the female the only nectar she will ever have in her life from the best gourmet restaurants in the area. This may take hours but it is an important task as it provides the female the necessary nutrient supply for her to produce her eggs, which she will lay in the soil after some days. Well, it looks like a happily ever after ending to this “waspish” love.

However, the Australian orchids of the genus Caladenia have managed to get in the way of this romantic story by transforming it into a love triangle. The labellum, or lip, of its flowers mimics the body of a wingless female wasp almost perfectly, calmly waiting for its beloved flying prince. The Caladenia flower even releases a similar scent that resembles the pheromone of a sexually receptive female. It has the right colour and the main features of the female wasp body. Déjà vu, don’t you think?! However, Caladenia flower has some more elaborate features. Its sexual organs, male and female, are strategically located on top of a column above the flower lip. You may wonder if that has not ruined the resemblance with a female wasp. The male wasps hunt down insects some weeks before the females show up at the surface and it is during this time that the Caladenia orchids exhibit their most appealing flowers. As he reaches maturity and is ready to mate, a male wasp is attracted by the pheromone released by Caladenia orchids. Without hesitating he lands on the false female, grabs her and tries to lift of. However, that he firmly grabs is attached to a special column. With his vivid and insisting movements on such a hard to get female, the best the male wasp manages is to turn himself upside down in a way that his back touches the tip of the column where the flower sexual organs are. This way he is presented with a patch of pollinia glued on his back. This unpleasant treatment does not seem to dissuade him. Upon realizing that was not a lady wasp, the male flies away and it is very likely that he will be fooled again. If this happens, on this second visit the pollinia patch will be removed by an already visited flower. As before the orchid gets its job done. Do not worry, the male wasp appetite was not affected by this bad date and surely he will meet real wasp gals.

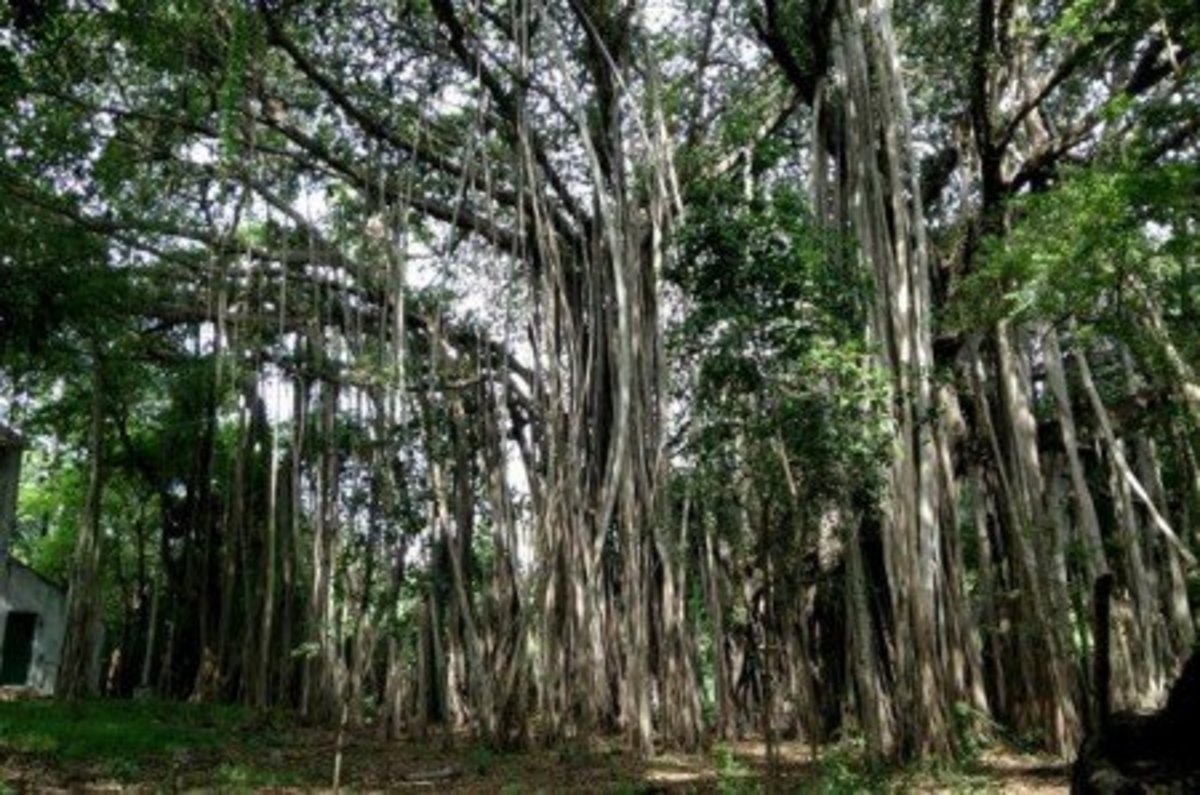

One of the the cruel orchids

Some Curious Facts about Orchids:

- The word orchid comes from the Greek órkhis, which means testicles, due to the resemblance to testicles of the tuberous roots, usually in pairs, of some European orchid species.

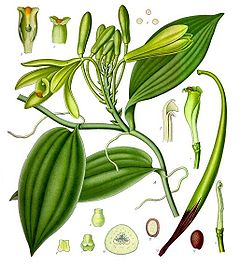

- Orchids are usually praised and cultivated for their beautiful flowers and today more than 100,000 different hybrids and cultivars have been produced. However, they can serve also as food; in this case, the most famous is Vanilla planifolia, from which vanilla flavour is extracted.

- According to Greek mythology, orchids appeared from the transformation of Orchis, son of a nymph and a satyr, into a flower. The gods punished Orchis after his attempt of raping a priestess of Dionysios. For his insult, he was torn apart by the Bacchanalians. His father prayed for him to be restored, but the gods instead turned him into a flower, from which its tuberous roots should remind us of his sinful life.

The Good Ones

Note that not all species of orchid have these complicated relations with their exquisite pollinators. Some in fact do reward well their pollinators. In fact, in some casesthe link i sso strong that they supply the only food that pollinator takes. Darwin's comet orchid, Angraecum sesquipedale, is one of these most popular examples. Darwin's comet orchid rewards with nectar its only pollinator, a sphinx moth from Madasgacar. When Charles Darwin first observed this orchid species, he suggested that the flower was pollinated by a then undiscovered moth with a proboscis (mouth parts) whose length was then unprecedented and thus seriously doubted. Many of his colleagues disbelieved that such an animal could ever exist. However, his prediction was not verified until 21 years after his death when the moth was finally discovered and his conjecture vindicated. This story of a close relationship between a plant and its specific pollinator has come to be seen as one of the celebrated predictions of the theory of evolution.

Darwin's Comet Orchid and Its Strange Pollinator

More about Plant-Animal Interactions:

- The Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, and Its Fearless Alies

Bullhorn Acacia, Acacia cornigera, native of Central America is best known for its symbiotic relationship with a species of ant that lives in it the hollowed-out tree thorns. The ants are famous for defending the tree fearlessly against ravaging in - The Aerial Life of the Ant Plants Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia

This group of plants, the ant plants, from the genera Hydnophytum and Myrmecodia, found an efficient way of living and surviving under adverse conditions. The reason for that success lies on the unusual relation that these plants established with the - The Admirable and Forget-me-not Nepenthes Plants

Apart from being very popular house plants, nepenthes or pitcher plants, as they are more popularly known, have one of most ingenious and effective way of luring and catching their mineral supply - insects. They are evolved flowering plants native fr - The Amazing Life of The Western Underground Orchid

The exraordinary life of an udnderground orchid, living in Australia only. - The Irresistible Powers of the Corpse plant, Helicodiceros muscivorus

In Mediterranean islands of Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic islands grows the corpse plant, Helicodiceros muscivorus. If found an unusual yet efficient and smelly way of sucessivly atract blowflies as its main polinators.