The History of Chewing Gum, from Its Mesolithic Roots until Today

Chewing, a 10,000 year old habit

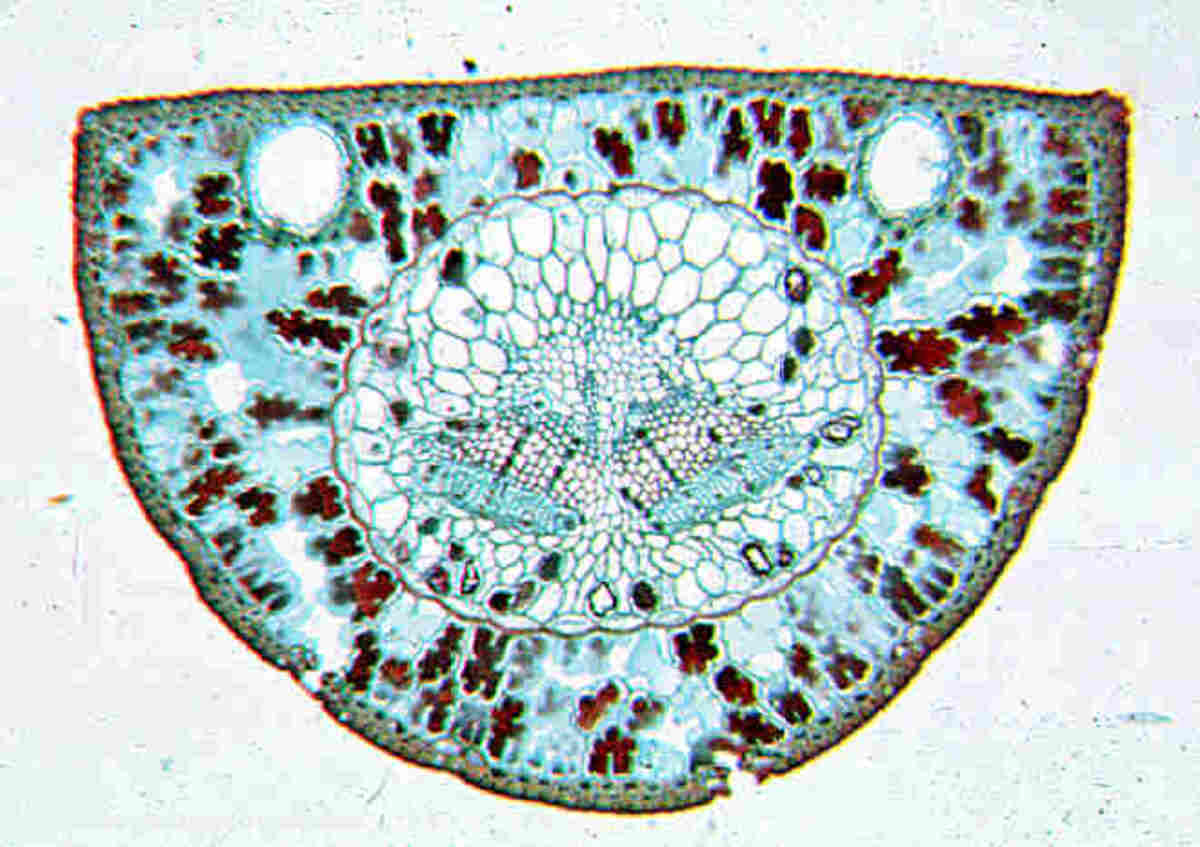

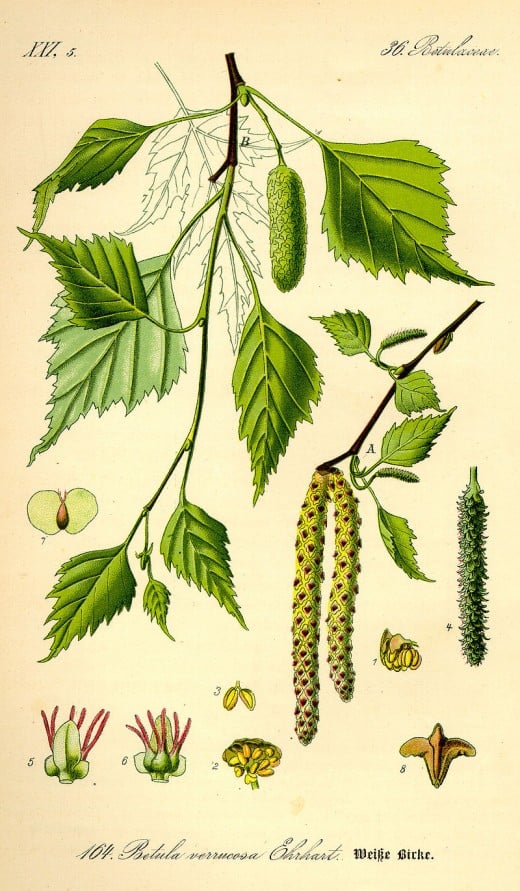

Many of us would think that chewing gum is something invented in the United States by William Wrigley Jr. or Thomas Adams in the late nineteenth century and later spread to the rest of the world in the following century. However, they were not original, and chewing gum happens to be something almost as old as humans themselves, judging by some archaeological findings. Archaeologists have found evidence of Early Mesolithic children, of about 10,000 years ago, taking part in the daily work tasks of their group by chewing resin, from birch (Betula spp.), to be used as an adhesive and for sealing, among other things. They have observed teeth marks in the chewing gum and resin lumps, respectively. It is thought that these chewing gums obtained from birch resin would be chewed for its antiseptic qualities. Not only do the phenols and other compounds it contains protect the gums from infections, but chewing also stimulates the production of saliva, which protects the teeth (if there is no sugar, of course).

The Tears of Chios

Probably, the oldest records of an “industry” of resin extraction and transformation come from the island of Chios where its inhabitants dedicated a great deal in making cuts on the bark of the older parts of mastic tree, Pistacia lentiscus, not touching the newest ones, in late July early August. Resin would then ooze from the cuttings running down the branch, or stem, slowly, crystallizing and accumulating in small lumps that would then be collected in late summer – the tears of Chios. Although limited, the activity is still practiced today more or less in the same way as in old times. Chios, in the Aegean Sea, is located less than 10 km away from the Turkish coast (west of Izmir) and is known today not only for being supposedly the birthplace of Homer but also for exporting mastic. The Venetians and Genoese, who dominated the island for four centuries until it passed in 1566 to Turkish rule, were the first to market mastic. Mastic was so valuable that during the Ottoman rule, it was worth its weight in gold. For those who ventured and got caught in stealing mastic, death penalty was what waited for them. Greece regained control of the island in 1913. The tears of Chios are still one of the main ingredients in local gastronomy and cosmetics of the eastern Mediterranean. Some of these products, e.g. Turkish delights, are famous internationally. Mastic also gives name to a much appreciated alcoholic beverage, Mastika.

Greece and Aegean Sea

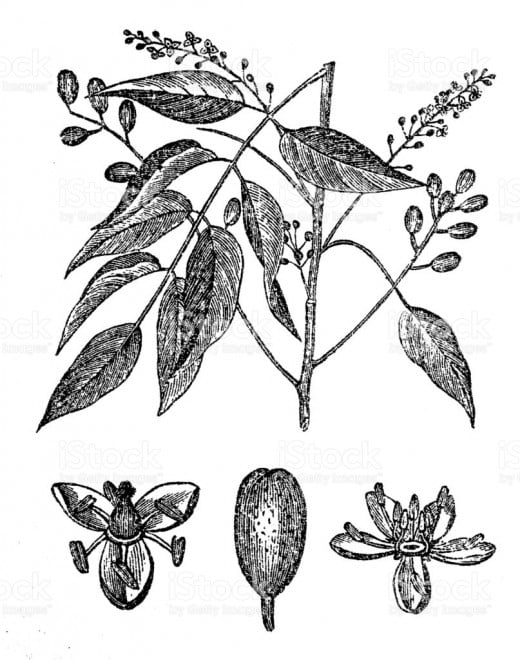

Mastic Tree

Mastic tree, Pistacia lentiscus, is an evergreen dioecious shrub or small tree, i.e. with separate male and female plants, growing up to 7 m high, with a strong smell of resin, in dry and rocky areas in Mediterranean Europe. It is a hardy plant that resists heavy frosts and grows on all types of soils, e.g. limestone areas and even in salty or saline environments, making it more abundant near the sea. It is a very hardy pioneer species typical and well adapted to the Mediterranean climate, dispersed by birds and serving as protection and food for birds and other fauna in this ecosystem. When older, it develops some large trunks and numerous thick and long branches covered with alternate, leathery, and compound paripinnate (i.e. with no terminal leaflet) leaves with five or six pairs of deep-green leaflets. Both female and male flowers are quite small and arranged in spiciform panicles. The fruit is a drupe, first red and then black when ripe, of about 4 mm in diameter. It is edible and quite popular in some areas where it is eaten fresh, cooked, salty, grilled, and used in many different ways. Apart from its long historical use in the Mediterranean, mastic has also become quite popular as an ornamental species.

The Cure of All Diseases

The Romans attributed the virtue of firming the gums to mastic toothpick. They even called those holding mastic toothpicks continuously as lentiscum arrodere, mastic chewers. Mastic was and still is used to preserve teeth whiteness, mouth breath, and gum firmness. Christopher Columbus, knowing the therapeutic effects of mastic at Chios and considered it almost a panacea (i.e. a remedy for all ills or difficulties), claimed in the famous letter of February 1493 to the Chancellor of the Treasury of Aragon, Luis de Santángel, that he had discovered mastic in the New World. However, what he thought to be mastic, Pistacia lentiscus, was in fact the gumbo-limbo or turpentine tree, Bursera simaruba, which the natives claimed (in sign language) to possess the therapeutic characteristics similar to mastic. In fact, even before Galen referred to it, the therapeutic virtues of the ancient Greece mastic were evidenced in some reference works, notably by Dioscorides. Pedanius Dioscorides, author of the famous work De materia medica that remained an important source of information on medicinal plants until the eighteenth century, refers to the very diversified curative powers of mastic. The mastic was considered for centuries almost the Grail of medicine that would cure even the black plague. Although it is not a universal panacea, in recent years its therapeutic action has been much investigated.

Other Sources of Chewing Gums

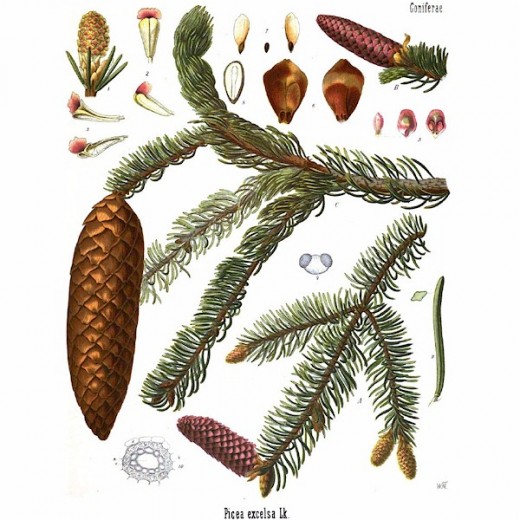

Even without the excuse of its therapeutic effects, it is certain that chewing the equivalent of the modern chewing gums, either from resins, gums or latex from different plants or even raw whale skin, muktuk of Inuit people, is an ubiquitous habit that has been with us for millennia. For example, as their ancestors, the New Zealand Maoris chew kapia, which is made with resin from the kauri tree, Agathis australis, mixed with latex from the puha thistle, Sonchus kirkii. In North America, the Native Americans used for the same purpose fir, Abbies spp., a habit they passed to North American settlers. In Central America, the extraction and processing of the white latex from sapodilla, Manilkara zapota, known as chicle is is the only legacy of the Mayan civilization. Wounded stems of red, Picea rubens, or black spruce, Picea mariana, release resin that flows into the wound and hardens upon contact with air, thereby sealing the wound. This resin is caned spruce gum, and was the first commercial chewing gum. The novelty of spruce gum made it popular: rural Europeans have been chewing it for centuries, and in early Sweden spruce gum was considered a present for a potential sweetheart the Scandinavian equivalent of a box of chocolate. Among the devoted chewers was Mark Twain's Torn Sawyer, who shared some with Becky Thatcher one day after school.

Modern Times, The Beginning

The first factory, State of Maine Spruce Pure Gum, was founded in 1848 by John Bacon Curtis and 12 years after with its 200 employees and its output of 150 tons of spruce pure gum produced almost 2,000 boxes of gum per day. Although the spruce gum business originally thrived its popularity soon waned. One reason for spruce gum's decline may have been its unusual taste, which one expert likened to "sinking your teeth into frozen gasoline." Moreover, it turns hard and crumbly when stuck to the bedpost overnight. However, the death of the industry was also due partly to the increased demand for newspapers, which prompted foresters to clear vast forests of spruce to make newsprint. Faced with dwindling supplies of spruce, manufacturers started looking for alternatives. Their first choice was paraffin, a by-product of petroleum distillation. However, paraffin, never really caught on, despite being the first gum to be sold in packets including picture cards. Today, paraffin is still available in semiedible novelties such as wax fangs, wax lips, and wax buck teeth.

Chiclets

A more successful substitute for spruce gum was chicle, the chewable latex of the Mexican sapodilla tree. Chicle was introduced in the United States by former Mexican President Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna, who brought in the first shipments of chicle to the tire production as a substitute of the natural polymer, rubber caoutchouc, which Charles Goodyear vulcanized a few years earlier. However, Santa Anna's efforts to produce rubber from chicle were unsuccessful as were Thomas Adams, a Long Island photographer who met the former Mexican dictator in 1869. There are several stories about what motivated Adams to think of chicle as chewable material, but it is undeniable that in February 1871 one could buy Adam’s New York Gum, the forerunner of the current Chiclets, quickly flavoured first with liquorice, Adam’s Black Jack, then with other flavours. In 1888, the Tutti-Frutti tablet produced by Adams began to be sold in automatic machines at New York subway stations. The great expansion of the chewing gum business was handled by an ambitious young man named William Wrigley Jr., son of a soap industrialist. Wrigley had the idea of offering yeast with the familiar product marketed in 1891, the Wrigley's Scouring Soap. He quickly start selling yeast with an offer of chewing gum, when he discovered that yeast was a more sellable product than soap. Chewing gum proved to be a commercial success and Wrigley, who set up the first brand advertising campaign, quickly outstripped the Adams-led company.

Central America

Extracting and Making Chicle in Central America

You might find it interesting:

- On the Multiple and Varied Sources of Resin, from th...

In a previous hub I talked about the origin, main uses and economic importance of resin and its derivative products. Now I will describe the main sources of natural resin and the reasons behind their extraction and production. Although pine resin acc - The Incredible Uses of Resin: From the Ancient Egypt...

The origin and the very different uses of resin and its economic importance from ancient times until today. - The Pará rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis: How Brazi...

The rise and fall of the Pará rubber tree, the natural source of rubber. The epic journey of rubber that started over 3000 years ago.

© 2017 Paulo Cabrita