Cinnamon: The Extraordinary Solving of a Millennial Mystery

A Very Old Mistery

Cinnamon is one of the oldest plant species known to man. It was already known to Phoenicians, Greeks and Egyptians as early as 2000 BC. However neither of them knew its origin nor its nature. They only knew its powder or its dried bark strips and it was often confused with a similar species cassia, Cinnamomum aromaticum, of Chinese and Burmese origin. The mysterious nature of cinnamon contributed to its high value and the most fantastic explanations were given to its origin, nature and “powers”, as well as myths associated with cinnamon. The mystery ended only when the Portuguese, during their golden discoveries era (fifteen to sixteen centuries) where the first westerns to identify and describe the plant, Cinnamomum verum, native from Sri Lanka, at the time known as Ceylon. According to the sixteen century Portuguese physician, naturalist and pioneer of tropical medicine, Garcia de Orta: "The trees are of the same size as Olive trees (...) white flowers (...) with black and round fruits, bigger than cowberries, more like hazelnuts (...) the leaves resemble laurel (...) and the root exudes cold water that smells like camphor". His remarkable knowledge of Eastern spices and drugs is revealed in his only known work “Colóquios dos simples e drogas he cousas medicinais da Índia” (Conversations on the simples, drugs and medicinal substances of India), published in Goa in 1563. This work of Garcia de Orta would influence other scientists, such as the physician Cristóvão da Costa, a pioneer in the study of plants from the Orient, especially their use in pharmacology. Cristóvão da Costa would complement the study of Garcia de Orta with his first work “Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias orientales” (Treatise of the drugs and medicines of the East Indies) in 1578. The first scientific illustration of cinnamon was then made in order to accompany the descriptions of the plant.

Today cinnamon is mostly used to name the powder or the inner bark strips of the small evergreen tree cinnamon, Cinnamomum verum, of the Laurel family, Lauraceae. Its previous scientific name Cinnamomum zeylanicum was derived from the popular and ancient name of Sri Lanka, Ceylon. The flowers, which are arranged in panicles, have a greenish color, and have a strong distinct odor that could be detected at about 8 leagues (about 24 miles) from the coast according to testimonies of sixteen century Dutch navigators. The fruit is a 1 cm purple berry containing one seed only. Today, there are many cultivars grown in many regions of the world. Like all members of the family Lauraceae, cinnamon has aromatic oils in their leaves and bark. The genus Cinnamomum contains over 300 species, distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of North America, Central America, South America, Asia, Oceania and Australasia. The genus Cinnamomum includes a great number of economically important trees besides cinnamon:camphor tree, Cinnamomum camphora; cassia, Cinnamomum aromaticum; and Selasian wood, Cinnamomum parthenoxylon.

Only for the Gods

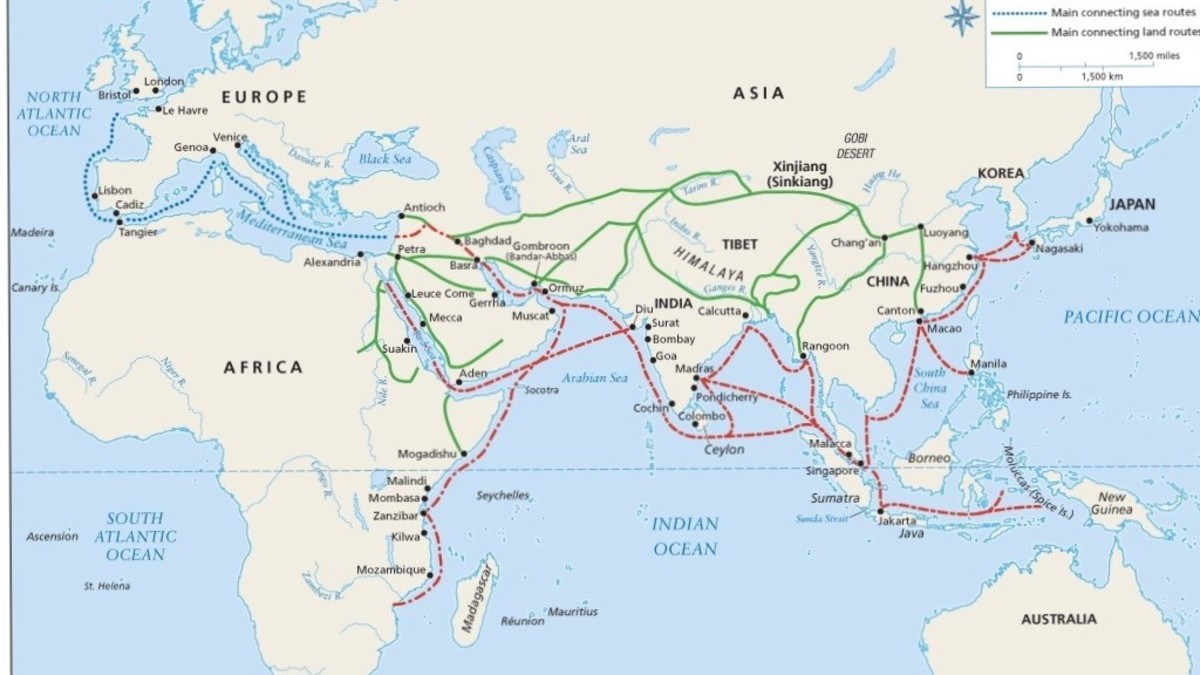

Cinnamon was so highly prized among ancient nations that it was only meant for monarchs and very important religious ceremonies, as for example offerings to a god. As an example of its high importance, it is said that the Roman Emperor Nero burned a year's worth of the city of Rome cinnamon supply at the funeral of his wife Poppaea Sabina, in AD 65, who died at his hands. The price of cinnamon was too expensive to be commonly used on funeral pyres in Rome. Europeans knew that cinnamon came up the Red Sea to the trading ports of Egypt, but its true origin was a total mystery. To Herodotus and other authors, Arabia was the source of cinnamon where giant cinnamon birds collected the cinnamon sticks to construct their nests. Cinnamon trees grew on unknown place and the Arabs tricked the birds to obtain the sticks. This story was current as late as 1310 throughout Europe. Although, Pliny the Elder, in the first century, had written that the traders had made this story up in order to make cinnamon more valuable and thus charge more. The first mention of the spice growing in Sri Lanka was made by the Persian physician and naturalist Zakariya al-Qazwini in about 1270. Not so long after there is a letter from the Italian Franciscan missionary John of Montecorvino of about 1292 mentioning the origin of cinnamon in Ceylon. Traditionally, cinnamon was brought via overland trade routes by Arab traders to Alexandria in Egypt. Cinnamon was then bought by Venetian traders who held the cinnamon monopoly on the spice trade in Europe. The disruption of this trade as to other valuable goods and the threat posed by other Mediterranean powers, such as the Mamluk Sultans and the Ottoman Empire, was one of many factors that led Europeans to search more widely for other routes to Asia.

Mistery Solved

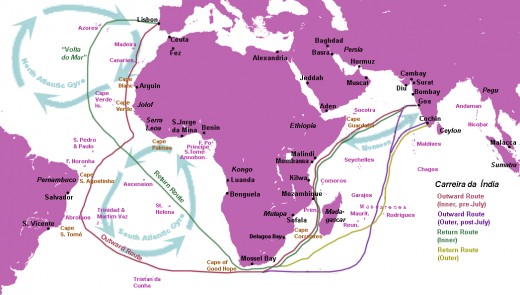

In 1487, Portuguese king John II sent Pero da Covilhã on an official mission to the East to inquire about the cinnamon and other spices that came from the Levant to Venice. However, it was only ten years after Bartolomeu Dias doubled the Cape of Good Hope, during the reign of Manuel I of Portugal, who continued the project initiated by his cousin and brother-in-law king John II, that the quest for spices reached the land of wonders in the East: India. On May 18, 1498 Vasco da Gama and his fleet are the first to reach India by a complete sea route, anchoring at Calicut. There in Calicut, Vasco da Gama and his men got to know not only that Malacca was the biggest emporium of all species from the East, but also the origin of most spices: they were all from the Malabar coast, Southwestern India. Pepper and ginger were indigenous to that region while cinnamon came from Ceylon, further south. In Calicut, on their very first day, Alvaro Velho provides an important description of the economic geography of the Indian Ocean in his journey diary. Although incomplete, it describes the intense and prosperous Indian trade in that region, which was of utmost importance to the main objectives of the Portuguese. In the same reports, Alvaro Velho refers to the island where "all fine cinnamon" is produced – Ceylon. It should be noted that in addition to this information, king Manuel I of Portugal already had descriptions of Ceylon from Marco Polo (thirteenth century) and from the Venetian merchant Nicoli di Conti (fifteen century), where the East was reported as fabulous land. Upon the return of Vasco da Gama, Manuel I, taking into account all this new information, wrote a jubilant letter to the Catholic Monarchs (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) communicating not only that explorers had reached their destination, but also that they have found a beautiful land, very fertile and rich in spices identifying it as the mythical land Taprobana referred by Greek geographers. Portuguese went to East with the aim of reaching not only the sources of production of spices, as well as building new routes there, since it was a very lucrative trade, even before the rounding of Cape of Good Hope by Bartolomeu Dias in 1488. Until the arrival of the Portuguese, it was Muslims who brought spices and other products to Europe, so the Portuguese penetration in the East was, of course, hampered by the Turks and Muslims who then found themselves seriously threatened in their work as commercial intermediaries between Europeans and the world. This occurred upon arrival of the Portuguese to Calicut, when Muslims realized that the Portuguese could be very serious commercial competitors. King Manuel I soon becomes aware of the economic and strategic importance of the island of Ceylon. For this reason, the first contact is established in 1505; however unsuccessful. It was only with viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque, Duke of Goa, that the monarch whishes came true. Afonso de Albuquerque established the foundations of the Portuguese empire by conquering important cities situated at strategic points: Goa in 1510; Malacca in 1511 and Ormuz in 1515. When the Portuguese arrive in Ceylon, the island was divided into three kingdoms that were rivals which allow the Portuguese to establish their power easier. The Portuguese sought to establish contacts with the king of Kotte as it was mentioned as the source of cinnamon at the port of Kerala. However. the cinnamon trade, even before the arrival of Portuguese, was held by foreigners only. It is only in 1518 that the Portuguese established a fortress in Colombo and for protection the king of Kotte was obliged to pay an annual tribute of 400 bahares of cinnamon (about 24,000 kg). But as this tribute quickly fell apart, the fortress was besieged in 1521.

The Golden Era

The Portuguese crown dominated and monopolized the cinnamon business several times, notably in Ceylon the only market of fine cinnamon. This business was so important that the Portuguese kingdom restructured the traditional production and management of cinnamon by the Sinhalese and reserved for itself the monopoly of navigation instituting the Carreira de Ceilão (Ceylon run). Thus, every year a ship would travel from Cochin (now Kochi) to Colombo bringing goods and money to the fortress and then it would return to Cochin to supply cinnamon necessary to "ships of the kingdom" that would then sail to Goa. The cinnamon surplus was meant for Asian trade mostly. This trade strategy soon became profitable as the price of a bahar (about 60 kg) of cinnamon could rise tenfold in the Malabar Coast. King Manuel I was thus ahead of all the Portuguese maritime trade, which was, therefore, the monopoly of the crown. Thus, cinnamon was not only the usual load in Portuguese ships, but also the main commodity that the sailors were allowed to bring home. According to the Renaissance Portuguese poet Sá de Miranda: "(...) at the smell of cinnamon the kingdom depopulates". Ceylon was then the Portuguese El Dorado. In the sixteenth century Ceylon is at the center of maritime trade routes, exporting cinnamon from the different ports of the island to the entire Indian Ocean. It is also from the early sixteenth century that the regular traffic called Carreira da Índia, the India run, started with an annual armada of Portugal putting into service a new route –the Cape route connecting Lisbon to India that would then supply Europe of famous oriental spices. Goa, Malacca and Macao later became the main Portuguese trading posts. But it was from Goa that the ships sailed towards Portugal through the India run. Goa was the headquarters of the Portuguese government and therefore the Portuguese capital in India. This new oceanic routes made the millennial Mediterranean spice route losing gradually its importance, as the spices brought by sea by the Portuguese reached Europe much cheaper. In Lisbon, the control and administration of the Eastern trade was made by the Portuguese organization Casa da Índia (India House). There were dealt issues of various kinds: signing of commercial contracts; payments were made and the prices of products were arranged. Despite the difficulties with the Portuguese presence in the East, the India run was a landmark and set a period of great worldwide economic changes.

As Always All Good Things Come to an End

The end of the Portuguese cinnamon monopoly came when Dutch traders finally dislodged the Portuguese by allying with the Sinhalese inland Kingdom of Kandy. After years of failed attempts the Dutch finally established a trading post in 1638 and took control of the Portuguese cinnamon factories by 1640. By 1658 all the remaining Portuguese were already gone. The Dutch East India Company continued to improve the methods of harvesting cinnamon in the wild and eventually began to cultivate its own trees. In 1767, Lord Brown of East India Company established the still existing Anjarakkandy Cinnamon Estate near Anjarakkandy in Cannanore (now Kannur) district of Kerala. This estate became the first and largest cinnamon estate in the world at the time and marked the mass production of cinnamon. As before the Sinhalese saw once more foreigners taking control of their island. This time, the British took control of the island from the Dutch in 1796. However, the importance of the monopoly of Ceylon was already declining fastly, as cultivation of the cinnamon tree spread to other areas worldwide. Also the more common and cheaper cassia bark (Cinnamomum aromaticum) became more acceptable to consumers. Coffee, tea, sugar, and chocolate later began to outstrip the popularity of this traditional and still popular spice. Today, Sri Lanka still produces almost 90% of the world’s cinnamon while Indonesia is responsible for about 40% of cassia production. However, the days where 1 kg of cinnamon was worth of 10 g of gold are far long gone.

Cinnamon's Origin

What About:

- The Sacrifice of Brazilwood (Caesalpinia echinata): How It Helped to Build an Empire and Giving Birt

The story of the rise and fall of Brazilwood. How it created and shaped the form of a new country. - The Fabulous Destiny of The Snake Pine

The unusual, old and rare pines that exist along the central Portuguese Atlantic coast. - Plants and Portuguese Discoveries: How Americans Got Addicted to Banana and Indians Spiced Up with M

Many of our most useful, tasteful and favourite food and plants have made a long journey to reach our tables at home. That journey began long ago and some of those plants changed European and Asian societies dramatically. Know more about how and why - Tobacco: The Incredible Journey of a Notorious Killer and How It Saved One of the Most Famous Artist

The Age of Discovery, initiated in the fifteen century, introduced many plant species to many different regions throughout the world. Some plant species changed society and economy dramatically and their effects are still present. Here is the story o