- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Napoleon in Egypt: A Grand Plan

The General

Introduction

By the start of the 18th century, Egypt’s glorious heyday of the Pharaohs was already more than three thousand years distant. From 1517 onwards Egypt had come under the rule of the Ottoman Empire; the people they deposed were called Mamluks, descendants of slave warriors that rose up against their masters in the 11th century, seizing control of the country. However, despite officially belonging to Istanbul, the Mamluks had managed to retain control over large parts of the country, in exchange for acknowledging the Ottoman’s as the overall rulers. As a result of this agreement, the Mamluks were allowed to prosper and regained much of their former power. However, the Mamluks did not represent a united front against the Ottomans. Instead, they mostly consisted of several tribal factions that spent more time fighting among themselves for control, rather than ruling the country together.

In 1765, a faction known as the Qazdagi emerged victorious over their rivals, supposedly signalling an end to the fighting, but the promise of peace was not forthcoming. For another twenty years, the fighting dragged on, agreements to cease the violence were continuously made, but no sooner had they been drawn up, they were broken, and the conflict rumbled on. Finally in 1785, a proper, permanent agreement put an end to the fighting. By this time, a faction led by Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey had emerged as the dominant force in Egypt. Such was their confidence, that they even started threatening foreign merchants, who brought in much needed revenue through taxation.

A year later, the exasperated merchants fed up of Mamluk hostility appealed to the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul to intervene. Truth be told, the Ottomans were already considering sending an expeditionary force to Egypt to recover what it considered to be the most valuable part of its vast Empire. In July, they launched an expedition and assaulted Cairo, successfully driving Ibrahim and Murad out and installing their hated enemy Ismail Bey as ruler. Ibrahim and Murad fled south, while the Ottomans satisfied that order had returned, pulled out. For several years, the rival Egyptian factions remained deadlocked in a standoff. While Ismail ruled the capital, Ibrahim and Murad ruled the south.

However, as you might expect the temporary ‘peace’ was not to last. In 1790, a devastating plague swept through Cairo, killing Ismail and most of his supporters. The following year, the Ottoman Sultan granted Ibrahim and Murad a pardon for their past crimes and allowed them to return to Cairo to rule once again. But their time in power proved disastrous, the infighting continued, they set ridiculously high taxes which all but obliterated Egypt’s trade. The once prosperous towns of Damietta and Rosetta lost half of their population, Cairo lost 40,000 people and even the iconic city of Alexandria was almost ruined. Egypt’s rulers were simply more concerned with their own personal power rather than dealing with the responsibilities of ruling a kingdom. In fact, it could be argued the disintegration of trade relations between France and Egypt was one of the many factors that led to the forthcoming invasion by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Recommended Links

- Napoleon in Egypt, or Egomaniac on the Loose

Napoleon in Egypt, or Egomaniac on the Loose. - French campaign in Egypt and Syria - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- French Invasion of Egypt, 1798-1801

Account of the French Invasion of Egypt, 1798-1801

Ambitions and Aspirations

France had cast its eye over Egypt for a while, and talk of invasion and setting up a colony was nothing new. The French expected the natives to actually welcome them as liberators from the brutal Mamluk regime. They also thought that the Ottomans would tolerate the invasion in exchange for subduing the increasingly confident subjects. The French held visions of blessing Egypt with the gifts of their own revolution, a modern government and the introduction of new laws favouring liberty, while casting aside older, archaic laws.

However, the role of the Ottomans had to be considered before these plans could be put into practice. The two had traditionally been allies, and despite their imperialistic ambitions, the French had no intention of making an enemy of the Ottomans. Their entire plan hinged on the assumption that the Ottomans would remain neutral at least. More ideally they hoped that they would consider the French to be some sort of necessary evil in order to vanquish an ancient foe. They expected Ottoman anger, but hoped it would diminish over time.

The French had also considered another important factor; Egypt was a Muslim country, although they did not take it too seriously. In fact, when Napoleon first addressed the Egyptian people, he proclaimed that he worshiped God more than the Mamluks and even went as far as saying that the French people are Muslims too. Unsurprisingly the people were not convinced by such bold statements, but religion would prove to be actually a relatively minor problem.

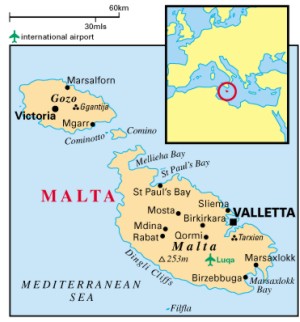

While France’s ambition was to gradually build a trading Empire stretching beyond Egypt, Napoleon’s own personal ambitions bordered on world domination. Firstly, he wished to seize the island of Malta, still ruled by a Christian faction called the Knights of St. John, like Egypt though, their glory days were all but a distant memory. Napoleon planned to use Malta as a naval base to strike out against Egypt and the Middle East. Beyond that, he wished to challenge British supremacy in India, restoring the French influence that had been extinguished in the Seven Years War. In order to execute such a bold strategy, he planned to dig a canal through Suez to allow French ships to reach the Red Sea. Napoleon’s mad ambition seemed to know no bounds, he wanted more than Egypt and India.

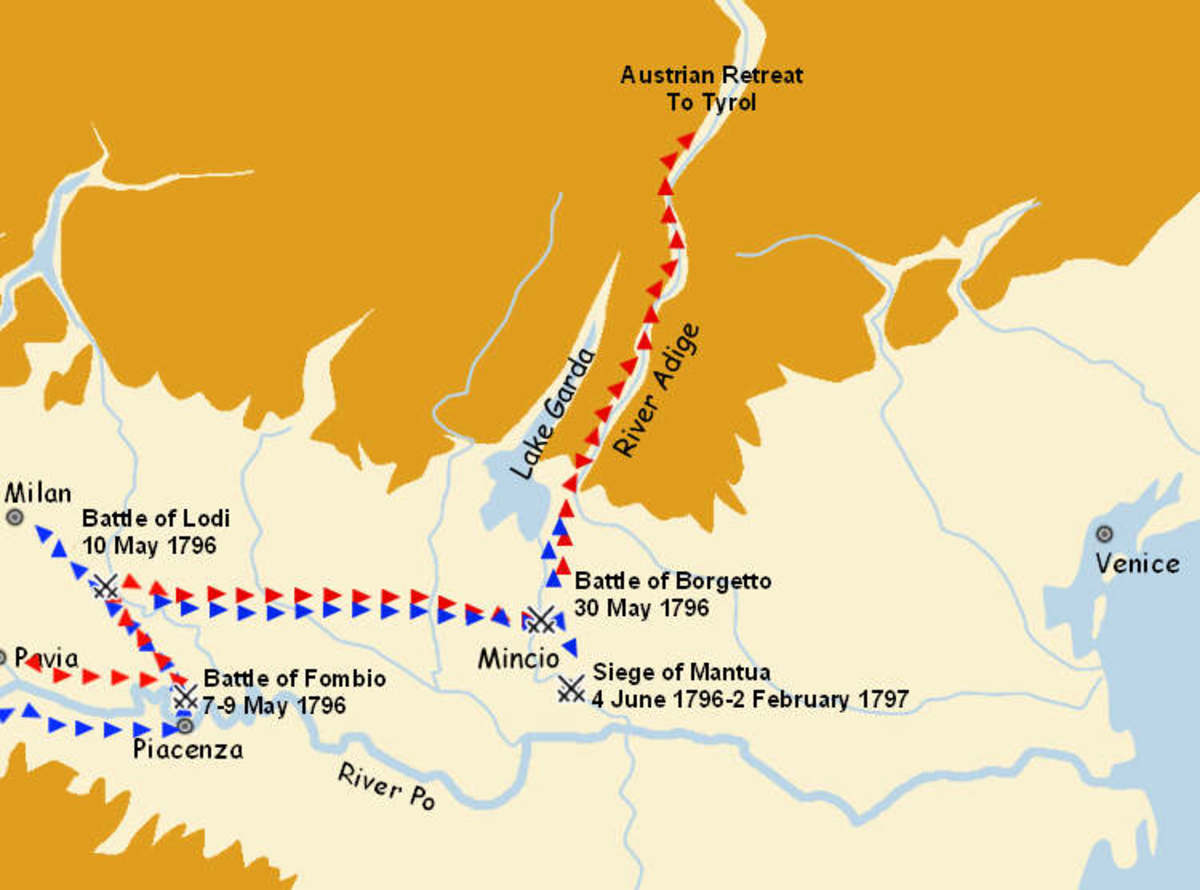

In the year 1798, the year the invasion was launched, he was 29 years old, at the time he is recorded as saying that Europe is far too small for an Empire and that all greatness is achieved in the East. Such a proclamation was a chilling throwback to the thoughts expressed by Julius Caesar who was worried that he had achieved nothing at a similar age, while Alexander the Great, idolised by both men had already conquered Persia by his 30th birthday. Napoleon’s grand plan was to secure Egypt, drive the British out of India, then rouse the dormant Greeks to rise up against the Ottoman Empire, capture Istanbul and restore it as Constantinople, the eastern beacon of Christianity. After that, he would attack Europe from the rear. It was a plan of grandeur and blind ambition, but judging from the size and skill of the French army of that period, it was certainly possible.

A Key to the Past

Making Ready

The French army destined to travel to Egypt was large, but nowhere near large enough to attempt any permanent occupation of Egypt on its own. The French government originally intended to deliver reinforcements, but that plan hinged on the ability of the French fleet to proceed freely in the Mediterranean without interference. Napoleon’s expedition consisted of 30,000 infantry, 2800 cavalry, 60 field guns, 40 siege guns and 2 companies of sappers and miners. This was deemed enough for to conquer and pacify Egypt; but the French would learn later that more troops would be needed to garrison the country and maintain a sizeable field army. Napoleon assembled an impressive cast of officers that would join him in the land of the Pharaohs: Berthier, Murat, Marmont, Davout, Kleber, Reynier, Junot and Dumas. In order to transport such a large army, Napoleon required a fleet the likes of which that had not been seen since the Crusades. He had 300 transport ships, 13 ships of the line and 7 frigates.

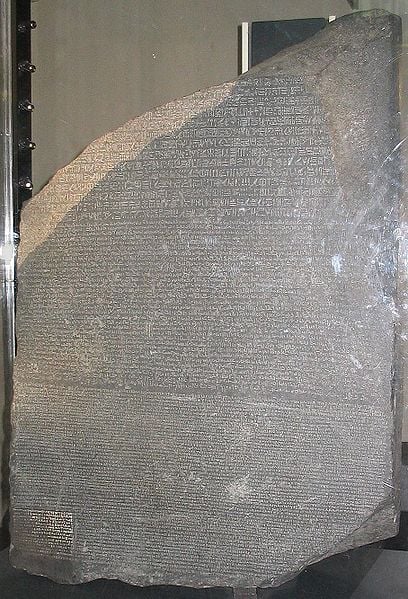

France’s expedition to Egypt wasn’t solely based on imperial glory; the army would be accompanied by a group of 167 savants that would go on to form the foundations of the new Academy Egypt. The work carried out by these French academics would have the biggest long term impact on the people of Europe at least. Perhaps their greatest discovery was the Rosetta stone, quickly followed by the decoding of ancient hieroglyphics and the subsequent revival of interest in Ancient Egypt. The expedition was prepared at an alarming speed and with almost total secrecy. The expedition was proposed in the first few months of 1798, by April it had received approval from Paris, a month later the huge flotilla launched from Toulon. The level of secrecy surrounding this ambitious venture was so impressive, that news of it only reached Britain in July. Even legendary British admiral Horatio Nelson took several months to catch up with the French fleet.

An Ancient Crest

Malta

Invasion

The Voyage

Napoleon set sail from Toulon on the 20th May, although the expeditionary force launched from several ports including Marseille, Genoa, Civitavecchia and also several ports on the island of Corsica, in order to ensure that their intentions remained secret. Even the soldiers were not informed of their real destination until they were well out to sea.

On the 9th June, Napoleon’s vast fleet was sighted off the coast of Malta, causing considerable consternation among the populace. The Grand Master of the Knights of St. John, an ageing Prussian called Ferdinand von Hompesch decided to send Napoleon a message asking what his intentions were. But it was a move made in vain, because the French had already landed men who had seized the unfortified ports of the island with barely a shot fired. Napoleon then dispatched one of his savants Dolomieu ashore, being a former Knight of St. John the hope was that he could influence his former colleagues to reach an agreement. Dolomieu however, was extremely reluctant and his negotiating skills were subpar, he was also acutely aware that the Knights could easily seize him and execute him for returning to Malta. The situation was further exasperated by Napoleon’s decision to send a man called Poussielgue, who had lived on the island as a spy barely a year before. When confronted with the delegation von Hompesch dithered, resulting in a tense standoff that lasted for the entire day. Under the cover of darkness, gangs of Maltese conscripts bearing torches stalked the alleyways hunting down and assaulting any Knights they could find.

On the 11th June von Hompesch surrendered under the guarantee that he would receive an annual pension of 300,000 francs from the French government. Over the course of the following week, the Knights were all sent into exile, each awarded a modest pension dependent upon their length of service.

The French spent a week, a week on the island, where Napoleon would exhibit his often very paradoxical character, as well as exiling the Knights he sought to abolish all other religious orders, reform the tax system and modernise the universities and hospitals. The flip side of the coin would see France exorcise military rule over Malta for the next two years. When Napoleon departed on the next leg of his journey, he also took most of the treasure, including items that had belonged to the Knights themselves. The year before he had stripped Italy’s famous cities of their treasure, such behaviour was utterly typical of the man.

The next leg of the journey would see Napoleon come desperately close to an encounter with Nelson’s fleet. As midnight passed on the 23rd June, French officers reported hearing signals guns from the British fleet. Napoleon appraised the situation and scoffed at any suggestion that the British could be in the Mediterranean. He decided not to raise the alarm, allowing the fleet to pass safely into the night. Nelson, on the other hand frustrated at not being able to locate the French fleet sailed north away from Napoleon. On the morning of the 1st July the French fleet approached the Egyptian coastline.

Egypt in 1798

More on Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

Invasion

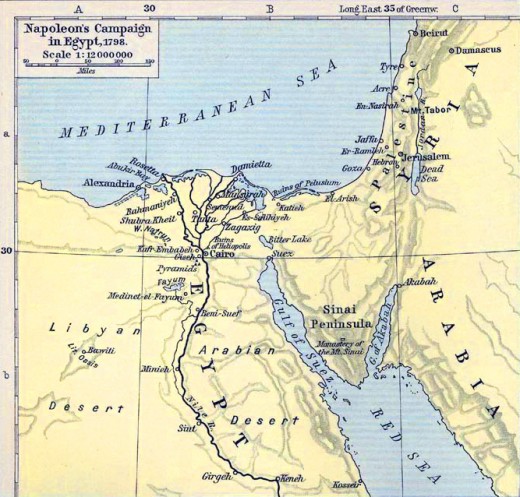

The campaign for Egypt began with Napoleon taking a risky gamble, deciding to dispatch 5000 men to land close to Alexandria, ignoring the advice of his commanders who suggested that the fleet should sail onto the Rosetta mouth of the Nile. Napoleon’s plan though was to have the 5000 capture Alexandria’s port thus giving him a safe place to land his forces. Fortunately the gamble paid off, mostly due to Alexandria’s inadequate defences. On the 2nd July, the ancient city originally conquered by Alexander the Great was in French hands. Bonaparte landed his forces and began a gruelling march towards Cairo.

The Mamluks were confident in their ability to overthrow the invaders, but it was a confidence borne out of ignorance of the potential and skill of the French army. They were also overconfident in their own military abilities despite having lost such an iconic city. Murad decided to lead a bold cavalry charge against the French at Shubrakhit on the 13th July but was easily by repelled by the impeccable square formations of the French infantry. The French pressed on towards Cairo, but the oppressive heat soon began to take its toll. The men soon complained of dehydration, flies and some even contracted fever. Unwisely, Napoleon had decided to invade Egypt when it was at its driest, although the Nile floods which quenched the parched landscape weren’t far away. Along the way, some French soldiers inevitably were left behind; these in turn were picked off by local Bedouin tribes. As Napoleon and his army approached Cairo, they found a vast Mamluk host waiting for them. Soon battle would commence for control of Cairo in the shadow of the mighty Pyramids.

More to follow:

References

Dwyer, P, Napoleon: The Path to Power 1769-1799, Bloomsbury Books, 2007

Rickard, J (16 January 2006) French Invasion of Egypt, 1798-1801,

Rothenberg, G, The Napoleonic Wars, Cassell, 1999

Strathern, P, Napoleon in Egypt, Jonathan Cape, 2007