- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

United States Mobilization at the Outset of World War II - Part I

The United States after World War I found itself embracing the ideals of isolationism and not wishing to ever again be involved in a European war. However, with the rise of Adolph Hitler and Nazi Germany in 1932 and then the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, America found itself on the brink of a war they were not wholly prepared for. Building the standing Army prepared to fight was a major initiative, which required instituting a draft and placing women in military roles. This mobilization to war also would require a significant change in manufacturing commerce on the home front to produce the military infrastructure that America was lacking. And then finally, the use of propaganda as a means to support, inform and raise moral of the American people to take part in the coming World War.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, America was mostly based on a civilian economy and clearly fell behind the curve in comparison to the powers they would be facing, who had for over eight years, dedicated half their national product towards war efforts as well as building their stockpile or armaments.1 When World War I ended, the United States made the decision not to join the League of Nations, thereby deciding that any involvement in international affairs was not an option. This, along with the nations view that a standing army was only necessary to be large enough to defend the nation, it's territories and possessions and being a small military force to be used for “planning and preparing for future expansion to meet contingencies.”2 Within the first month after the war, 650,000 officers and men were released as part of the demobilization plan by the United States War Department. After nine months, almost 3.25 million people related to military affairs had been demobilized, along with weapons and war materials. The active Army by 1919 had become an all-volunteer force of about 224,000 officers and enlisted men.3

By the time Adolph Hitler had invaded Poland in 1939, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his staff, fully aware of the threat that Germany presented, began a preparedness campaign. Advancements in technology made it possible for the United States to now be at risk, even across the ocean, from hostile forces. FDR had to walk a fine line between the ideas that any acts of mobilization would be seen by the isolationist society in America as a sign the president was positioning the United States for war.4 Another part of this plan was to increase the size of the Regular Army and National Guard. The draft was enacted in September 1940 and after the United States officially entered the war, draft induction was via lottery, and volunteers were still allowed only up until December 1942.5 It should be noted that the purpose of the draft was to equally share the burden of military service across a pool of eligible Americans, but deferments were not uncommon. These deferments initially took into account marital status, presence of children, and while not specifically deferred as a group, farmers, who were critical in the post-Depression stability of the United States.6

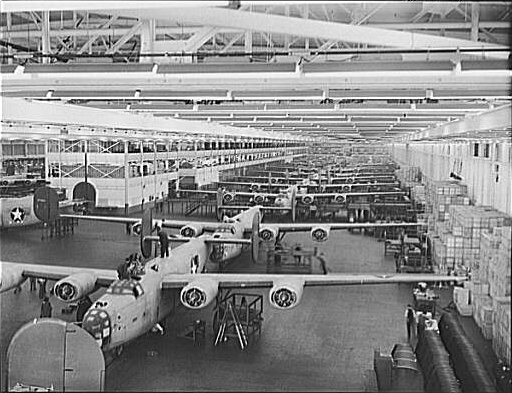

One of the biggest hurdles in mobilization efforts was due to the sub-standard military complex. Even after Pearl Harbor, most Americans, while clearly angered by the attack, felt that the continental United States was not at risk to be bombed, invaded or threatened. Overby points out that “The conflicts were an ocean away, and sustaining a popular commitment to production and economic sacrifice was an altogether different issue than it appeared in Britain or the Soviet Union.”7 Prior to 1941, the United States entire military expenditure was 4 percent of the entire amount spent until the end of the war. However, after 1941 the immense and rapid rise of the military complex made Allied victory possible. While most nations took anywhere from four or five years to significantly build up their military might, the United States did so in one year. This rapid advancement changed the United States from a sub-par military power into a world superpower.8

This rapid rise in military industry would serve the Allies well. For example, while the Japanese initially saw gains in the Pacific, the United States began out producing Japanese vessels sixteen to one, thus having the ability to attain victory simply by attrition alone. But this could not have happened by the government alone. FDR appointed automobile industrialist William Knudsen to oversee the Office of Production Management, and instead of the government telling American businessmen what to do he asked for volunteers to produce the list of military items necessary. This method was effective and American know-how in industry, mass production and technical and organizational skills were essential in the rapid advancement of the American military mobilization plan.9

Prior to 1941, American leaders lived in an isolationist view that if war was to come America would tackle it when it came and that by staying out world affairs the chance of war coming diminished. After 1941, however, it was clear that the world was a much less safe place for the United States than they had previously thought and that the US “had to be involved in world events, as it could not avoid their impact... the failure of appeasement suggested the US had to take a lead in opposing dictators and aggressors.”10

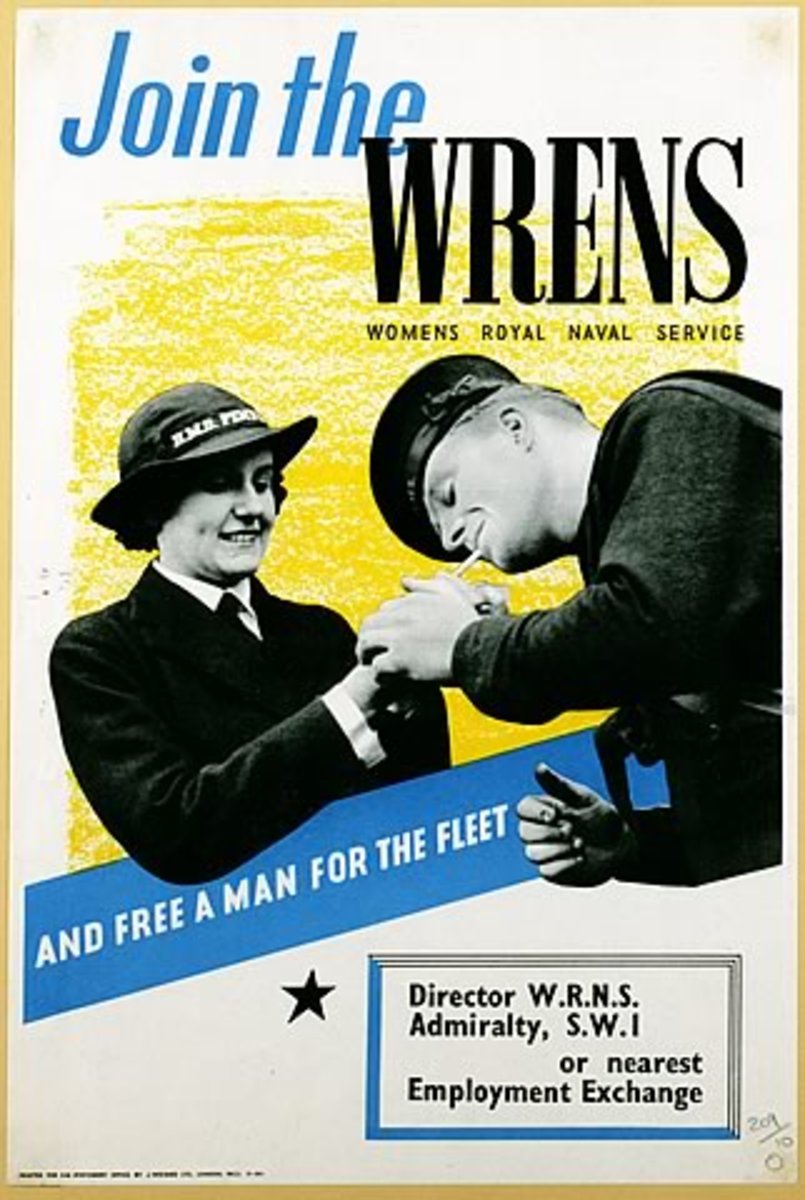

American mobilization efforts on the home front at the beginning of the war, and for that matter during the war, were a critical necessary in the success of the United States. Women's roles in the early stages of the war initially took the form of being attendants who registered men for the draft, but after Pearl Harbor the roles women were to have in the war opened a plethora of opportunities for American women to do their part. Civilian Defense Volunteer work, Red Cross assistance were standard fare, but of equal importance was the roles women would have to fill in industry with the male population heading to Europe. These women were now the head of household, a role traditionally held by men, and they now found themselves “faced with the difficulties of providing for themselves and their families in a time of rationing and shortages of both gasoline and food.”11 As the war gained steam, it was clear to the government and businesses alike that women workers in factories would be a necessity. In a pamphlet issued by the War Departments Civilian Personnel Division in 1943 it states that “More than 5,000,000 new workmen are needed for war production – more than half must be women.”12

In May 1942, women were allowed to join the military and massive amounts of women jumped at the opportunity to not only serve with their men, but place themselves on a higher ground than that of previously held ideals of the domesticated woman whose place was in the home. The number of women who signed up for the Women's Army Corp (WAC) and the naval equivalent WAVES skyrocketed to over 110,000 each.13 While not “officially” sanctioned for combat, women were called in to hostile areas to serve various “non-combat” roles such as clerks and by 1943 all the branches of the U.S. military had added women to their ranks.14 But this military role was not easy and came with a cost – that of image. Sexual stereotypes painted a picture of women as camp followers, mannish women, prostitutes or lesbians. Leisa D. Meyer gives a voice to this problem by relaying what a journalist observed after the war in that,

Of the problems that the WAC has, the greatest one is the problem of morals... of convincing mothers, fathers, brothers, Congressmen, servicemen and junior officers that women really can be military without being camp followers or without being converted into rough, tough gals who can cuss out the chow as well as any dogface...”15

Part II of this hub can be found HERE.

Sources

1 Richard Overy, “The Success of American Mobilization,” in Major Problems in the History of World War II, ed. Mark A. Stoler and Melanie S. Gustafson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003), 59.

2 Ibid., 59.

3 Ibid., 54-55.

4 Folly, Martin. The United States and World War II: The Awakening Giant. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), 18.

5 Timothy J. Perri, “The Evolution of Military Conscription in the United States,” Independent Review 17, no. 3 (2013): 433.

6 Ibid., 433.

7 Overy, The Success of American Mobilization, 58.

8 Ibid., 59.

9 Ibid., 60.

10 Folly, The United States and World War II: The Awakening Giant, 142.

11 Mary Weaks-Baxter, Christine Bruun and Catherine Forslund, We Are A College At War: Women Working for Victory in World War II (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010), 36.

12 United States War Department, “You're Going to Employ Women,” Washington D.C., 1943. 1.

13 Ibid., 120.

14 Ibid., 121.

15 Leisa D. Meyer, “Creating GI Jane,” in Major Problems in the History of World War II, ed. Mark A. Stoler and Melanie S. Gustafson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003), 275.