24 Reasons Why the "Golden Age" of Japanese Film Really WAS Golden (Part V)

20. The End of Summer [aka Autumn for the Kohayagawa Family] (Kohayagawa-ke no aki) (Dir: Yasujirō Ozu, 1961)

At first glance, this movie – Ozu’s penultimate film – would seem to be the diametrical opposite of the downbeat Tokyo Twilight (see Part IV), which Ozu had released just four years before. Instead of a visual palette of somber greys and blacks, this movie is in brilliant and beautiful color. As in Late Spring and Early Summer (see Part I), the plot seems to revolve around the dilemma of a reluctant “marriageable woman,” or rather of two such women (Yoko Tsukasa and Setsuko Hara). There is also a broadly funny subplot involving the mischievous family patriarch (Ganjirō Nakamura), who’s always sneaking away to meet with an ex-mistress, seeming far more childlike than his own grandchild. But by film’s end, it turns out that Ozu has been playing games with the viewer, for the film is really only about a death. And that death has repercussions for all the characters, for the family for generations has run a small sake brewery, and now they will need to sell out to a big corporation. So the end of an individual is also depicted as the end of an era… for the family as well as for Japan. One of the most memorable scenes in all of Ozu’s work is the one in which the deceased character’s body is being cremated, and the survivors stare at the column of black smoke rising from the chimney as if looking into their own graves, which of course they are – and so are we.

21. Harakiri (Seppuku) (Dir: Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

More than any film I’ve seen, Masaki Kobayashi’s masterpiece evokes for me the spirit, and even at times the form, of Greek tragedy. In 1630, the samurai Hanshiro Tsugumo (Tatsuya Nakadai) arrives at the imposing Iyi mansion requesting the privilege of committing seppuku – ritual suicide – on the grounds. Saito (Rentarō Mikuni), counselor for the Iyi clan, attempting to dissuade him, tells him about Chijiiwa Motome, a samurai who had also recently requested to commit seppuku there, hoping for a job, or a little money, from the clan. Instead, the Iyi had forced Motome to go through with the act, making his suicide a travesty. Tsugumo, undeterred, chooses to go through with seppuku anyway – but not before relating to the Iyi clan the sad tale of Chijiiwa Motome… his adopted son. As in a work by Sophocles, the powerless get to confront the powerful through the sheer force of their words. And when Tsugumo finally strikes, he does so not so much with his sword, as with the bushido code itself, his courage and skill exposing the clan’s hypocrisy and cowardice. The movie even has a Creon-like character in the person of Saito, wonderfully played by Mikuni. (One could argue that Saito is the most tragic character of all, as he must live with the knowledge of the utter emptiness of his clan and of the code they live by.) No movie has ever more creatively exploited the austere beauty of Japanese traditional architecture. Kobayashi makes of the Iyi mansion a kind of beautiful dark cage, within which Tsugumo’s furious revolt is as heroic as it is futile.

22. High and Low [aka Heaven and Hell] (Tengoku to Jigoku) (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

This amazing (and too little known) Kurosawa suspense thriller is the greatest Hitchcock movie Hitchcock never made. Indeed, it mixes seemingly incompatible cinematic genres in a way that Hitch would probably never even have thought of… and wouldn’t have attempted if he had. Set in modern-day Yokohama, the film starts out as a rather nasty drama of corporate intrigue. The hero, Gondo (Toshirō Mifune), who runs a successful shoe factory, plots to gain control of the entire corporation. But the story turns unexpectedly into a melodrama about a kidnapping, with the unseen kidnapper playing a cat-and-mouse game with Gondo. After that tense story line is resolved, the movie morphs into a complex police procedural, one of the best ever filmed. Then, again unexpectedly, the film turns into a modern-day vision of Hell – but you really have to see this picture to get it. It almost goes without saying that the director handles all these narrative twists and turns like a champion racecar driver, with great skill and utter self-confidence. What doesn’t go without saying is the strong social conscience – and class consciousness – that the director injects into what could have been a routine suspense film. High and Low is perhaps most noteworthy, however, for its dazzling bullet train sequence, one of the most famous of the many great set pieces in this director’s work.

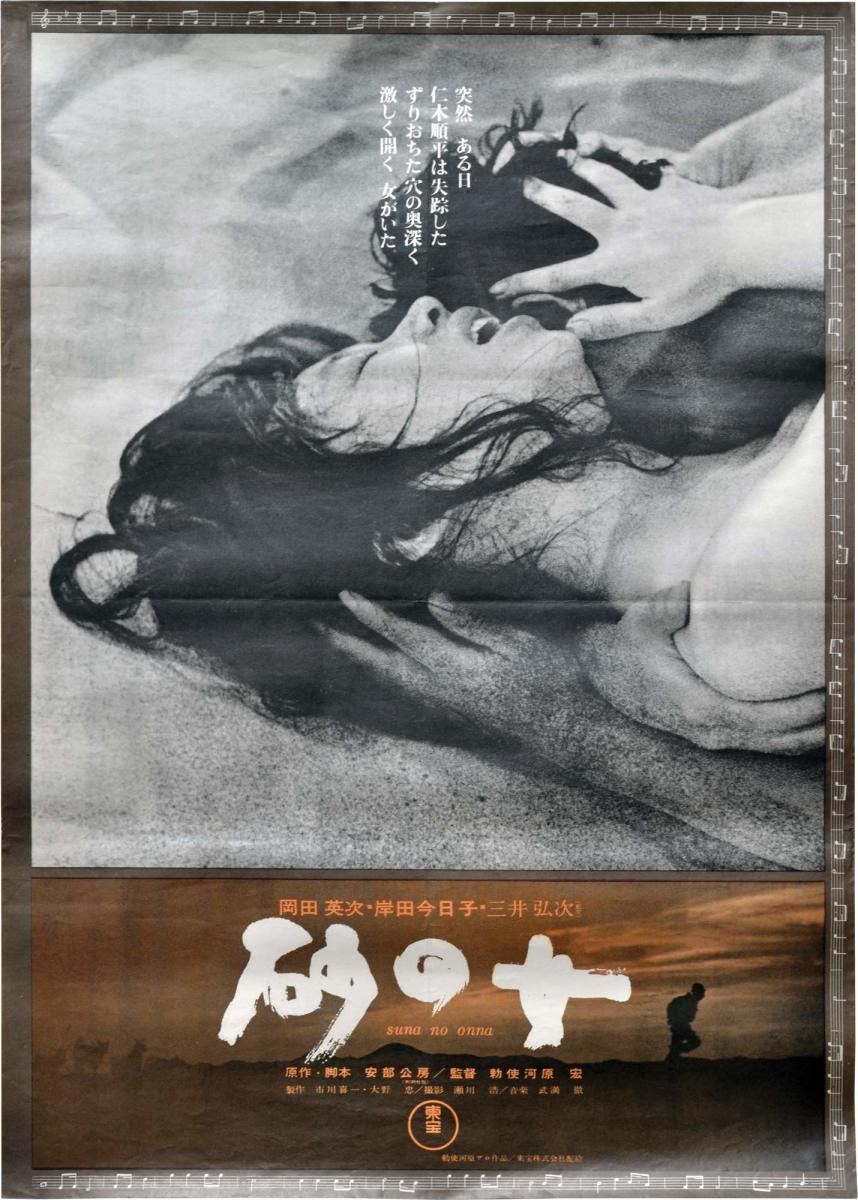

23. Woman of the Dunes (Suna no Onna) (Dir: Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

Though I’ve always admired this film, and still do, something about it has always bothered me, and a recent viewing clarified what that something is. Hiroshi Teshigahara directed this work from a script by the famous writer Kōbō Abe… but director and writer seem to me to be at cross purposes. Niki Jumpei (Eiji Okada), passing through a village on an insect-hunting trip, accepts an offer from the villagers to stay the night under the roof of an attractive widow (Kyōko Kishida), whose house happens to be at the bottom of a sand pit. By next morning, he realizes that the villagers and the widow expect him to stay forever with her, and join her in her life’s work of interminably shoveling sand. Abe clearly intended this tall tale to be an allegory of contemporary life. The man and woman endlessly shoveling sand, for example, could be a metaphor for any married couple trying to “dig” its way out of debt. The problem is that Teshigahara and the film’s brilliant cinematography (by Hiroshi Segawa) make this environment totally, tactilely real and utterly alien. Thus, it’s completely believable that Jumpei would desperately struggle to return to his futile – but infinitely more comfortable and comprehensible – life in the city. Very oddly, though the male character is given a name, the widow is just “woman” – or rather “Woman.” The movie thus leaves itself open to charges of misogyny, with Woman depicted as “entrapping” Man, both physically and erotically. But if that was Abe’s intent, Teshigahara, and Ms. Kishida’s performance, defeat him, and the widow ultimately emerges as the more sympathetic character of the couple. In the last shot we see of her, she is in labor, her face contorted in pain… and that ain’t no damn metaphor.

24. Red Beard (Akahige) (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1965)

It’s entirely fitting that our final example of Golden Age cinema should be Kurosawa’s Red Beard, a masterpiece that examines Japan’s historical past while also looking back at the humanism of its cinematic past. In 19th Century Tokyo, Kyojō Niide, alias Red Beard (Toshirō Mifune), serves as chief doctor of a clinic for the terminally ill and destitute. He forces Noboru Yasumoto (Yūzō Kayama), an intelligent and educated but very spoiled young physician, to work, at least temporarily, at his clinic. The upside of this plot is that the surrogate father-son relationship the two characters establish – after Yasumoto gets over his initial rebelliousness – is quite moving. The downside is that Yasumoto’s conversion to a life of compassionate service is all too predictable. Kurosawa handles this problem by allowing his narrative to meander into all sorts of fascinating byways, with the film increasingly focusing on its peripheral characters. Early on, Yasumoto survives a strange and nearly fatal encounter with a homicidal madwoman (played by, of all people, gentle Kyokō Kagawa, in a brief but brilliant performance). After he recovers, the young doctor decides to help an emotionally damaged girl (Terumi Niki) whom Red Beard had rescued from a brothel. The Dostoevskian world Red Beard evokes is one in which suffering is everywhere, but which at times permits an entirely secular kind of grace, represented by the figure of Dr. Niide. And though the film is deliberately old-fashioned (in a good way), Kurosawa was continuing to innovate: this was the first of the master’s films to feature a stereo soundtrack. It’s a pleasure to listen to this movie through headphones, not just for its lush music score, but for little details of the sound design that the filmmaker and his crew have so carefully crafted. By simultaneously pushing the film medium forward while harking back to its noblest traditions, Kurosawa, with this work, proved himself completely typical of Japanese Cinema… and, possibly, of the Japanese people.