Walls and Fences

A walled city

Pretoria is a walled city, like most of the major cities in South Africa.

Walls and fences are the most noticeable features of the residential areas of these cities, at least the formerly "white" areas, and this gives one a clue to the reason for these walls and fences.

It is not a walled city in the traditional sense, but is rather a city of walled off areas, where relatively small groups of citizens live behind electric fences and remote-controlled gates.

These walls and fences are not constructed against foreign invaders, as the traditional city walls were, but against themselves.

Which has gotten me thinking about the proverbs about "good fences make good neighbours" and the human desire to separate, to cut people off from each other.

We use many rationalisations, like defence and crime, but are these really the reasons for these walls and fences.?

I guess it all comes down to fear - fear of those different from ourselves, fear of ambiguity, fear of change, fear of loss, and perhaps even fear of looking too deeply within ourselves.

And so it goes on ...

- Slum walls raise suspicion in divided Rio - Mail & Guardian Online: The smart news source

When residents of a Rio de Janeiro slum heard of plans to build a wall around parts of their community, opposition to the idea quickly mounted.

The search for security

As people we look for security, for something that tells us we are not defenceless, not alone, not at risk. And yet, to live is to be at risk, to grow means to change, and as we grow we realise more and more that we are alone. We have to take responsibility for who and what we are, we can't blame anyone else, and that is somehow a fearful thing. We are alone because we are, each one of us, unique individuals, and the only real cure for this aloneness is to find others, to try to understand others, to find common cause with others in a project that is greater than our individuality.

And that is why I begin to question these walls and fences. Do they provide us with the security we want, do they give us opportunities to overcome our essential aloneness? As philosopher A.C. Grayling has noted, when there are walls separating people, "...they come together only to fight."

The result is that, to quote Grayling again, "The barriers make matters progressively worse, because as distance and ignorance increase it becomes harder for opponents to work their way back to mutual understanding, to reach compromises, and in them to make painful but essential concessions."

Walls and fences have separated people from the earliest of human settlement. In the archaeological record the oldest know walled city was that of Uruk, which was at its peak around 2900 BCE. It was a city of some 50000 people at that time, as far as can be determined, the biggest city in the world at that time. It was in the area now known as Iraq, a name which some think derives from the name Uruk.

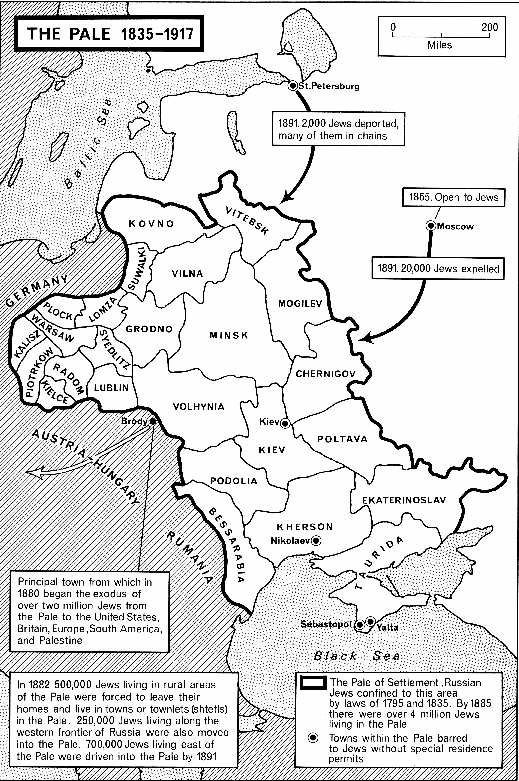

The list of walled cities known since then runs into hundreds. The practice of walling off sections of cities or towns, however, most likely dates from the formation of ghettoes built to keep, particularly, Jews, in a place separated from other citizens. This practice reached apogees in Nazi Germany and, by way of the Russian empire, in the "Pale of Settlement" created by Catherine the Great in 1791. This development led to the progroms against Jews in the later 19th Century and on.

The need for boundaries

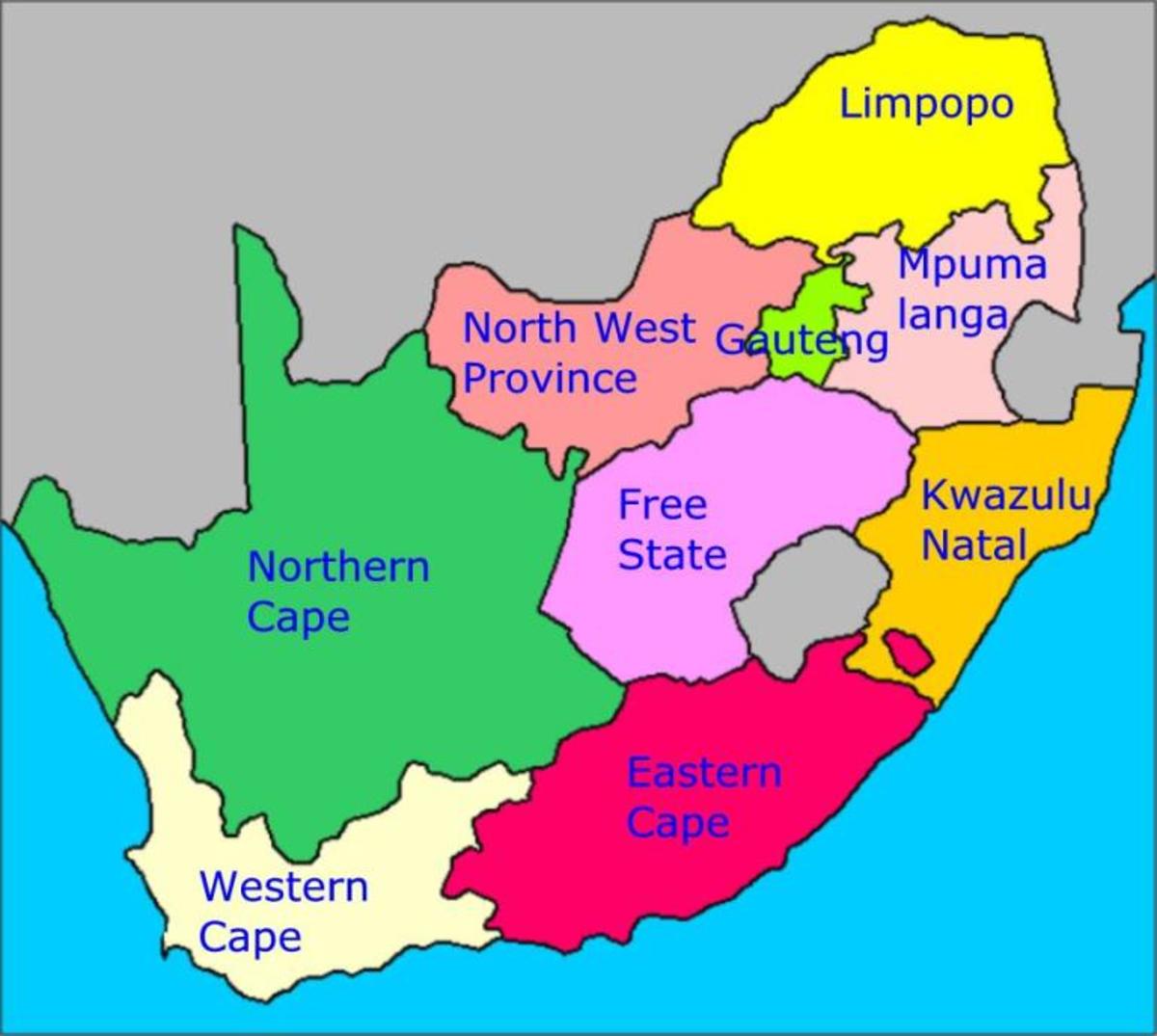

We in South Africa, of course, are experts at separation, from the first white settlers at the Cape in 1652 right up to the present day.

The leader of the Dutch settlement at Table Bay, Jan van Riebeeck,. was sent there to set up a garden to supply fresh produce to the Dutch ships which passed that way en route to India. One of his first acts, after establishing the garden, was to plant a hedge of almond bushes around it to keep the original inhabitants out. Apartheid was born.

Of course, the hedge failed, as have all attempts to separate people permanently anywhere in the world.

Is there a wall-building instinct built into our psyches as people? Certainly there is a need for us define ourselves in terms of who were are as individuals, which implies a kind of separation from others. Who am I as me, and who am I in relation to you? What is my place and worth in the world? These questions are natural and an important part of our being as humans. We cannot live without answers to these questions and how we find these answers is important as the answers define us.

Obviously these answers lead to what are called "boundaries" and these boundaries can be healthy and life-giving or destructive and life-denying.

These boundaries are important at micro-level (the personal boundaries) and at macro-level (boundaries between groups or nations or countries). Africa, a continent with manifold problems, is suffering from artificial boundaries imposed on people by the colonising powers in the 19th Century. These boundaries meant little or nothing to the people themselves, but were important for the colonising powers as they had to do with imperial prestige and the competition between the colonising powers. Africans became pawns in a bitter struggle about boundaries between the European powers, a situation in which they are still, to a large degree, trapped.

Psychological boundaries are life-giving to individuals and do not need to be life-denying between individuals or groups. If the boundaries are mutually agreed and understood, then they can be a source of peace and harmony - the proverb about "good fences making good neighbours" can be turned around to say that "good neighbours make good fences," a good fence being one that is mutually agreed and understood as opposed to imposed by one on another.

Dealing with ambiguity

More often, though, walls and fences, like proverbs, are attempts to "to free complex situations from ambiguity" as Wolfgang Mieder, Professor of German and Folklore at the University of Vermont, wrote in the 21st Katherine Briggs Memorial Lecture in November 2002.

This lecture is a fascinating study of the origins and history of the proverb which plays such a powerful role in Robert Frost's 1914 poem "Mending Wall":

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, 'Good fences make good neighbors.'

Separation and security

Another factor of separation in South Africa, one which harks back to the ghetto, is those suburban areas found in most cities, which are euphemistically called "gated communities."

These in fact are ghettoes, ghettoes of the "haves" with security fences and walls meant to exclude the "have-nots," ghettoes of exclusion rather than inclusion. In apartheid South Africa they were exclusively white, but now that is no longer true, as more and more Blacks join the ranks of the "haves" and feel the need to protect their privileges. And to call them "communities" strains the meaning of that word to a huge degree.

What all these wall and security fences do is fragment further an already fragmented society, entrenching the deep divisions in a country which has a huge gap between poor and rich, one of the biggest in the world, as measured by the Gini coefficient, which in South Africa hovers around the 0.7 mark. (an equitable society would be more towards the 0.0 end of the scale which goes from 0.0 to 1.0, the higher the coefficient the greater the gap.)

So these walls also are in the long bound to fail, and indeed might increase levels of insecurity and violence. Because as security measures are increased, so will the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those determined to breach any such security.

As Grayling said in the same article quoted earlier, "The barriers make matters progressively worse, because as distance and ignorance increase it becomes harder for opponents to work their way back to mutual understanding, to reach compromises, and in them to make painful but essential concessions."

Walls and fences do not make good neighbours, they make fearful and jealous ones. The make neighbours who are bound to look for more and more physical security measures and thereby put their psychic health at risk to an intolerable degree.

Because really the only security we can have is the security that comes from knowing oneself, one's fears and hopes, and in recognising these in those around us. "Mutual understanding" is the key to peace and will not be found behind walls and fences.

Walls - unresolved historical issues?

Having said that, I know that people are risk-averse, and opening up to others is a risky business, so walls and fences are an easy answer in the short term.

To quote Grayling again, "When individuals get to know one another, it is usually impossible for them to like or hate each other on the basis merely of generalities about race, religion or history. To hate successfully, you must hate an abstraction — the totality of Arabs or Jews or whomever — because once you put a face to a person, and with it a home, children, an enjoyment of hamburgers or football, all abstractions melt."

I'm not sure that I fully believe that "all abstractions will melt" when we get to know the other person as an individual, but what I know for sure is that those abstractions become fixed in those who huddle in fear behind walls and fences.

Ironically, South Africans, and especially Afrikaners, were in the historical past more likely to agree with the old Cole Porter song, "Don't Fence Me In" (the lyrics for which were originally written by Montana based poet Robert Fletcher):

"Oh, give me land lots of land under starry skies above

Don't fence me in."

Indeed the early Afrikaners left the confines of the Cape colony in search of "land, lots of land" in an attempt to break away from the confines of law and order which the colonial authorities tried to put them into.

But of course that movement brought them into direct competition with the Black people, who were moving south and west as the Afrikaners moved north and east, with the inevitable result of more conflict and misunderstanding, a struggle between two opposing forces which seemed to the participants at the time, amenable only to a violent solution.

So the walls of today in Pretoria and elsewhere in South Africa express historic issues which have still not been resolved, more than 200 years later. Is it still true that it is only possible to really be oneself behind walls and fences?

"Walls"

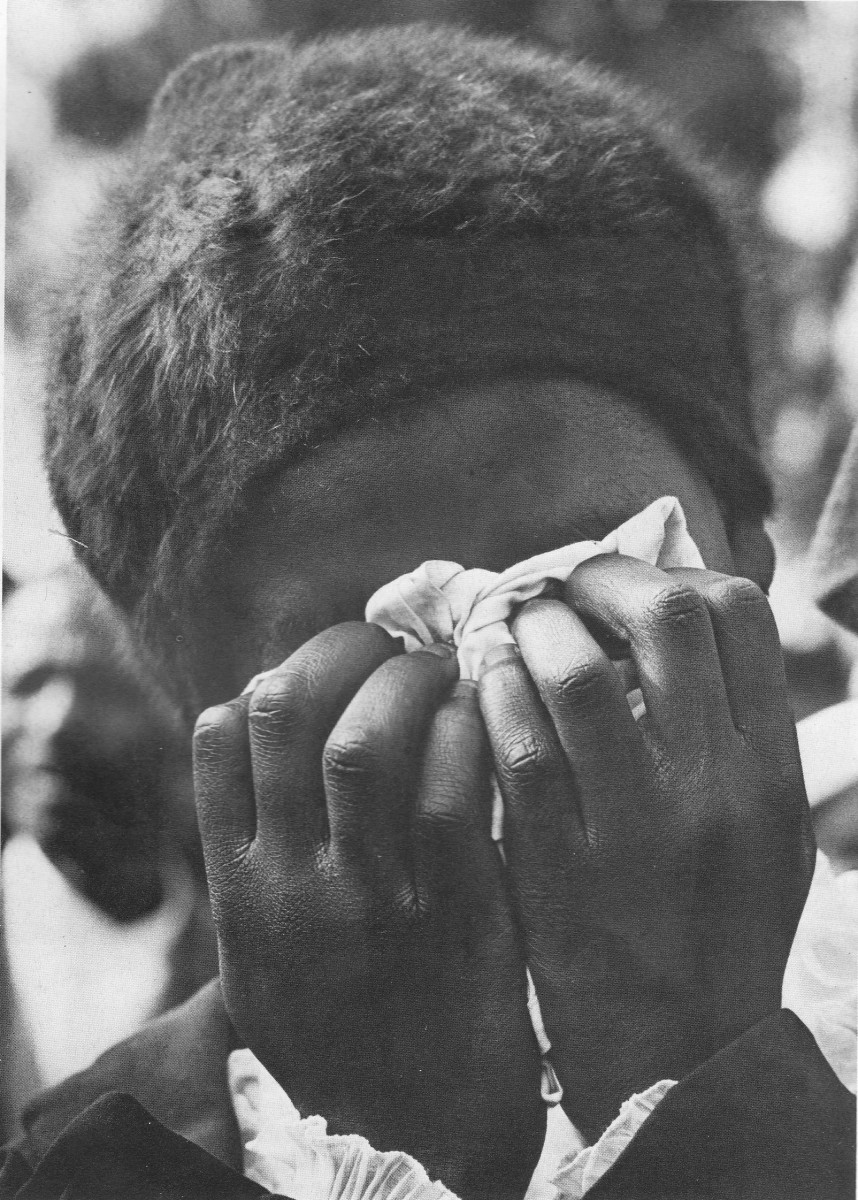

The separation caused by apartheid led to many in South Africa musing about walls and fences - and using the metaphor in different ways. This poem by South African poet Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali is a powerful one.

Man is

a great wall builder -

the Berlin Wall

the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem

but the wall

most impregnable

has a moat

flowing with fright

around his heart.

A wall

without windows

for the spirit

to breeze through

A wall

without a door

for love to walk in.

- Weeping Lyrics

Here are the Weeping lyrics written by Dan Heymann.

- Let's Build the Spaceship Peace

We all were born on this spaceship called planet Earth, and this spaceship doesn't know any borders. To understand this, step back and try to watch this spaceship from the outside. You will see that rivers... - "Borders and Walls"

The Great Wall of China is one of the worlds greatest wonders: a gigantic structure, the only one we see from space. It is indeed a testament of great human determination,... - IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT ON THE LINE

Its the time of the year when our government checks out of the office for a three-week vacation! Adjourned until September, they are taking their health care agendas, pro or con, back home to constituents....

Afterword

One of the most evocative uses of the wall metaphor came out of apartheid-era South Africa in the form of a song written in 1987 by a conscript, a very unhappy conscript, in the South African Army which at that time was "defending" the South African borders against the forces of liberation led by, in the main, the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC is now the ruling party in South Africa, as it has been since the 1994 democratic elections.

This conscript doing his "border duty" was a young man called Dan Heymann, who just happened to be a musician. Heymann began writing music and words to express his anguish at being in an army which was fighting to defend what, to Heymann, was indefensible, the separation and oppression of Blacks in South Africa. The words of the song "Weeping" express the horror of forced separation and the inevitable violence needed to maintain the separation that was at the heart of the apartheid ideology:

He built a wall of steel and flame

And men with guns, to keep it tame

Then standing back, he made it plain

That the nightmare would never ever rise again

But the fear and the fire and the guns remain

Heymann, who now lives in New York, has written the following explanation of the metaphor in his song:

"The man referred to in the Weeping lyrics is the late P. W. Botha, one of the last white leaders of South Africa before the end of the Apartheid regime; The demon he could never face in the Weeping lyrics refers to the aspirations of the oppressed majority, while the Weeping lyrics also refer to the neighbors, literally the journalists from other countries who were monitoring the situation in South Africa.

That pretty much sums up the metaphorical content of the Weeping lyrics."

"Weeping" was recorded by the band Bright Blue, of which Hermann was a leading member, in 1987, at the height of the state of emergency declared by the apartheid regime in order to try to stem the rising tide of resistance to the apartheid state.

The recording, which included a strong instrumental reference to the anthem of the ANC, "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika", nevertheless quickly charted in South Africa, spending two weeks in the number one spot. It has since been covered many times, including at least two versions by popular US singer Josh Groban. A beautiful tenor sax solo is also a feature of the Bright Blue version of the song, played by the man who became identified with Abdullah Ibrahim's monster jazz hit "Mannenberg", the late great Basil Coetzee.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2010