South Africa’s Mother City at the Fairest Cape

Complex history of a beautiful city

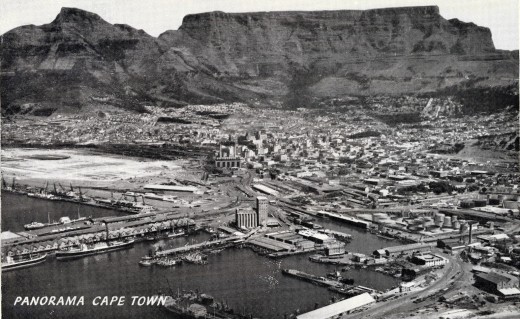

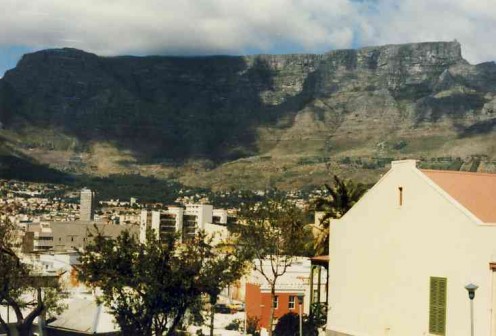

The course of the history of Southern Africa was dramatically changed on 6 April 1652 when Dutch East India Company (VOC, for Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) official Jan van Riebeeck came ashore from his ship the Dromedaris. Where he landed the city of Cape Town now stands, in the shadow of beautiful, brooding Table Mountain.

Van Riebeeck and his men were of course not the first people in the area. Indeed the area had been inhabited for more than 10 000 years already. Evidence has been found at Peers Cave above Fishhook of human habitation. In addition there is rock art dating back many centuries in the caves of the Cape Peninsular.

The consequences of the landing of the Europeans have grown across the centuries. At first Van Riebeeck was given strict instructions not to create a permanent settlement at the Cape but only to start a garden and barter with the local inhabitants for cattle and sheep, both for the purpose of re-victualling the ships of the company as they rounded the Cape on their way to India and the East Indies in search of spices and other luxuries for the European market.

Soon it became clear that such an undertaking could not be based on a temporary presence but that a permanent settlement would have to be allowed to grow there, that the people, no less than the crop plants, would have to be allowed to put down roots.

This led inevitably to the disintegration of the social structures of the indigenous Khoikhoi people with whom the Dutch settlers came into contact.

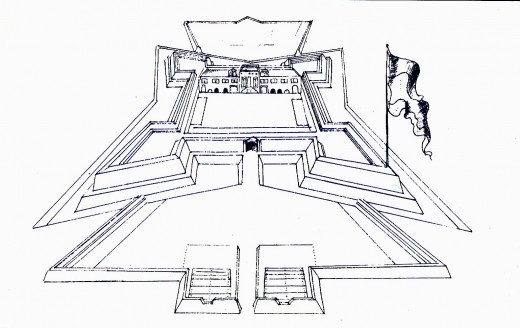

One of the first structures to be built was a fort to protect the settlers and the garden that Van Riebeeck planted to supply the ships of the Company as they came to anchor in Table Bay. And so began the expropriation of the indigenes’ land, slowly, almost stealthily at first, but gathering speed until by the late 19th Century they found themselves strangers in their own land, from the Cape to the Limpopo River, far to the North, and beyond, the agricultural and mineral wealth of what had been their land were now firmly in the hands of the settlers.

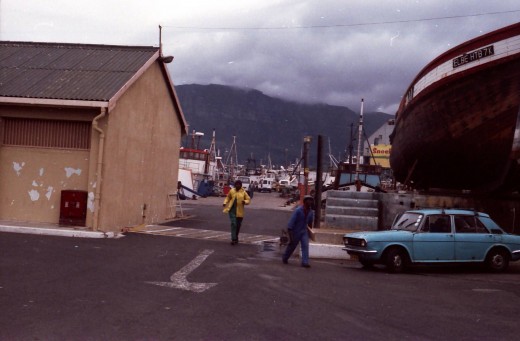

- Cape Town City images

Cape Town, where I am writing this, is a city of contrasts - old and new, rich and poor, and many other contrasts besides.

The fairest Cape

But all of that was far into the future and could not have been foreseen by the relatively raggle-taggle band of settlers who put their feet, at first rather tentatively, on the Southern African soil more than 300 years ago.

For them the struggle was to do what the VOC expected them to do – get together enough fruit, fresh water, vegetables and meat to meet the nutritional needs of sailors enduring long voyages under the most appalling conditions of cramped quarters, constant dangers from sea and weather, and extremely inadequate diet, not to mention the psychological effects of loneliness, deprivation and the sheer terror of venturing into the unknown.

Portuguese national poet Luis de Camoes wrote, while in Mozambique for two years, the famous epic poem Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) , in which he described the journey of Vasco da Gama in 1497, in dramatic and sometimes fanciful terms. The poem was published in 1572:

“It is hard to tell you of all the dangers we experienced and the strange happenings we saw in these lonely and faraway regions: the thunder, the lightning and those dark rainstorms in deadly black nights. I saw with my own eyes the incredible phenomena that are described by sailors but which more learned men believe to be untrue and illusory; I actually saw St Elmo’s fire spouting during storms from the metal at the tips of our wooden masts, and clouds drinking up the swells of the ocean, starting as a faint smear which swirled up in the wind.” (From Writers’ Territory , edited by Stephen Gray; Cape Town: Longmans, 1973).

Even the Cape was initially an object of fear, of the unknown. It was originally called Cabo das Tormentas (Cape of Storms) by the Portuguese sailors, and was only renamed Cabo da Boa Esperança (Cape of Good Hope) by Portuguese King John II as a result of the positive feelings engendered by the realisation of the sea route to the riches of the East.

It did indeed become a place of hope for the sailors after months at sea, who could look forward to fresh water and food there, and a place of surpassing beauty: "The most stately thing and the fairest Cape we saw in the whole circumference of the earth" as Sir Francis Drake had described it in 1580.

But in those early days of European exploration the Cape was an almost mythical place of fear, of the unknown, to most of those braving those southern seas, and was anthropomorphized into the prophesying giant Adamastor by Camoes. In the poem Vasco da Gama asks the giant who he is, and Adamastor replies:

“I am that mighty hidden cape, whom you call the Cape of Storms. I was never known to the ancient geographers, not to any other. Here the coast of Africa ends, pointing to the Antarctic pole, and it is I whom your daring offends. I was one of the Titans, giant sons of Earth and Sky. My name is Adamastor.”

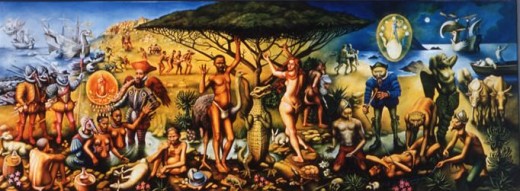

Artist Cyril Coetzee painted, on commission for the Cullen Library of the University of the Witwatersrand, a new interpretation of the Adamastor myth, called “T’Kama-Adamastor”, which, as he explained,

“...I had the idea of doing a computer search to see whether there was anything useful in the recent Adamastor literature. To my surprise, I found André Brink's short novel, The First Life of Adamastor. T’kama, Brink's central character, is a Khoi chief – and also a reincarnation of Adamastor. In a parody of the "discovery", he retells the story of the original colonial encounter "from the perspective of the 20th century". It was exactly the kind of contemporary reworking of the story of Adamastor that I had been fumbling to invent!”

This great painting brings the Adamastor myth into the 21st Century and is a good way to end this very brief overview of the origins of the modern, cosmopolitan city of Cape Town. It is, almost as Camoes wrote, after the darkness of slavery, colonialism and apartheid, the dawning of a new day:

“As the sun rose, we saw the land into which the giant had been transformed. We made a proud swing round the Cape and sailed a short while further down the coast, turning at last to face the East.”

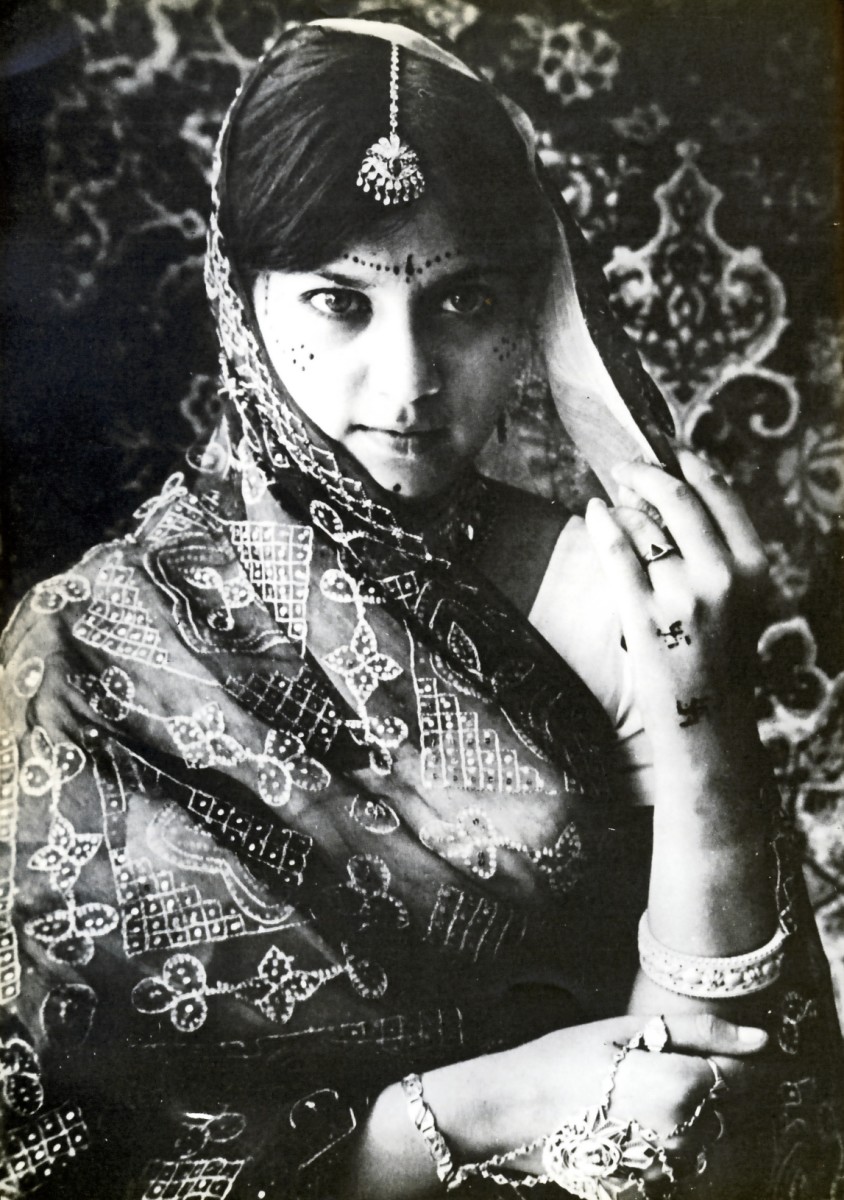

A Unique Culture

A distinguishing feature of Cape Town for me is its atmosphere, the culture of the people which is so deep and unusual, a coming-together of strands from so many different sources. Different peoples, languages and cultures have been thrown together into a great cauldron out of which a culture is emerging, not without pain and struggle.

One of the most devastating struggles for the indigenes was that between the early Dutch settlers and the Khoikhoi. Denis-Constant Martin notes in his fascinating book Coon Carnival (Cape Town: David Philip, 1999):

“The destruction of Khoikhoi societies and their integration into the colonial order had important consequences for the development of an original culture in the Cape Colony. Because Khoikhoi lived with Europeans and slaves, they sometimes acted as cultural brokers and, in the end, they exercised a considerable influence. Consequently, the ‘cultures’ of the Europeans, the slaves and the Khoikhoi became inextricably enmeshed.”

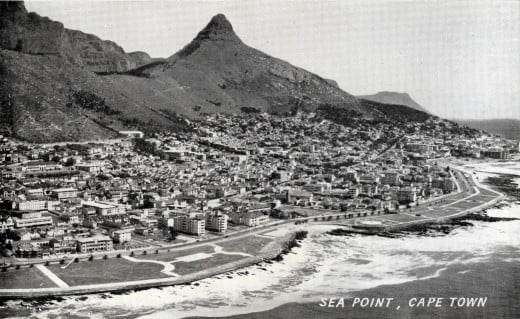

Cape Town embraces almost every human experience, symbolised by the hugely differing lifestyles and life-circumstances, from the shanties of the informal settlements on the Cape Flats to the stately homes of Constantia, from the rough-hewn crags of the mountains to the super-sophisticated technological wonders of the Cape Town International Convention Centre, and every conceivable stage in between.

This coming together of many cultures began to accelerate after the landing of Van Riebeeck and his party. As Martin notes, slavery was a foundational factor in the development of a South African culture. So an understanding of slavery and its reality in the Cape is essential to understanding the culture that is emerging there.

Slavery started at the Cape with the arrival of the first official slave there in 1653, just a year after Van Riebeeck had landed. His “slave” name was Abraham van Batavia, his real name not recorded. Martin describes slavery thus:

“It was dehumanising in many ways: slaves were abducted, deprived of their freedom, separated from their family and from all those who shared the same conception of life. They were uprooted, relocated and given new names. They had to serve foreign masters and had to live alongside other captives from different parts of the world who did not speak the same language and who did not have the same customs”

Two symbols of this cultural flowering in Cape Town are the related cultural forms of the Coon Carnival and the form of jazz known as “Cape Jazz”. Both of these cultural aspects are much debated, with many views being expressed about them.

Cape Jazz

The term “Cape Jazz” is much disputed and written about. The Wikipedia article on it defines it thusly: “Cape Jazz is a genre of Jazz, similar to the popular music style known as marabi, though more improvisational in character, which is performed in the southern part of Africa.”

Colin Miller, journalist and jazz enthusiast, in an article published on the “Jazz Rendezvous” website quoted Cape Town jazz musician Vincent Kolbe:

‘Now naturally you hear a lot of music. You learn to dance, you listen tentatively to the music; you listen to the rhythm, and you listen to things that encourage you to move. So you become sensitive to music. You also go to church. And there’s the organ grinding away and the hymns of all the ages and chants. And then Christmas! But on your way home from school, there’s a Malay choir practising ‘Roosa’ next door and there is even African migrants living in a kraal nearby singing Xhosa songs or hymns or something and you could have the Eoan Group practising opera at the church. Then there’s the radio and the movies. And you see this man conducting and his hair flowing in his face so naturally you go and fetch your granny’s knitting needles and you let your hair fall over the face and you conduct. So that’s the whole thing, movement and dance and imitation and living it’.

So Cape Jazz is the music which naturally flows out of the cauldron of culture that is Cape Town, mixing so many influences into its rich stew.

The list of musicians whose names are most often associated with the Cape Jazz term is a long and honourable one. Among the most notable of these are Abdullah Ibrahim, Chris McGregor, Winston Mankunku Ngozi, Basil “Mannenberg” Coetzee and Robbie Jansen. Also on the list are Chris “Columbus” Ngcukana and his sons Ezra and Duke, Monty Weber, the Schilder “dynasty” of musicians including Chris, Tony and Hilton, and Errol Dyers. New names coming into the field are Mark Fransman and Kesivan Naidoo.

Greenmarket Square

Built in 1699 between Shortmarket and Longmarket streets and in the shadow of Table Mountain this square has been in turn a slave market, a vegetable market, and before its most recent use as a flea market, a parking lot.

It is surrounded by interesting buildings, some with great historical value, such as the Old Town House.

The square was also the scene of many anti-apartheid demonstrations over the years, the most famous being the “Purple Rain Protest.” This protest was held just before the elections of 1989 and was marked by the use by police of purple-dyed water sprayed from a powerful water-cannon onto the protesters who were marked by the purple dye for easy identification. Within hours of the police action t-shirts were on sale in Cape Town bearing the slogan “The Purple Shall Govern,” a reference to the phrase from the 1955 Freedom Charter “The People Shall Govern!” A book with the same title was also published.

The square is often used also for concerts, especially of jazz during the annual Cape Town International Jazz Festival. One such occasion was the tribute to Chris McGregor concert in the Carling Circle of Jazz series in 1987.

One of the absurdities that emerged from apartheid manifested itself on the Square in the late 50s. A white visitor from the Free State province went to the toilet which still stands in the middle of the Square. Here he found himself standing next to a “coloured” man also answering the call of nature. He was so incensed at having to use the same toilet facility as a “non-white” that he wrote to the City Council demanding that the toilet be segregated, evidently on the assumption that it would be reserved for the use of whites. The Council decided to take a survey of the use of the toilet facilities and found that coloured people made most use of it and so reserved the toilet for the use of coloured people. One can only speculate about the reaction of that man from the Free State if he ever had to answer the call of nature in that vicinity again.

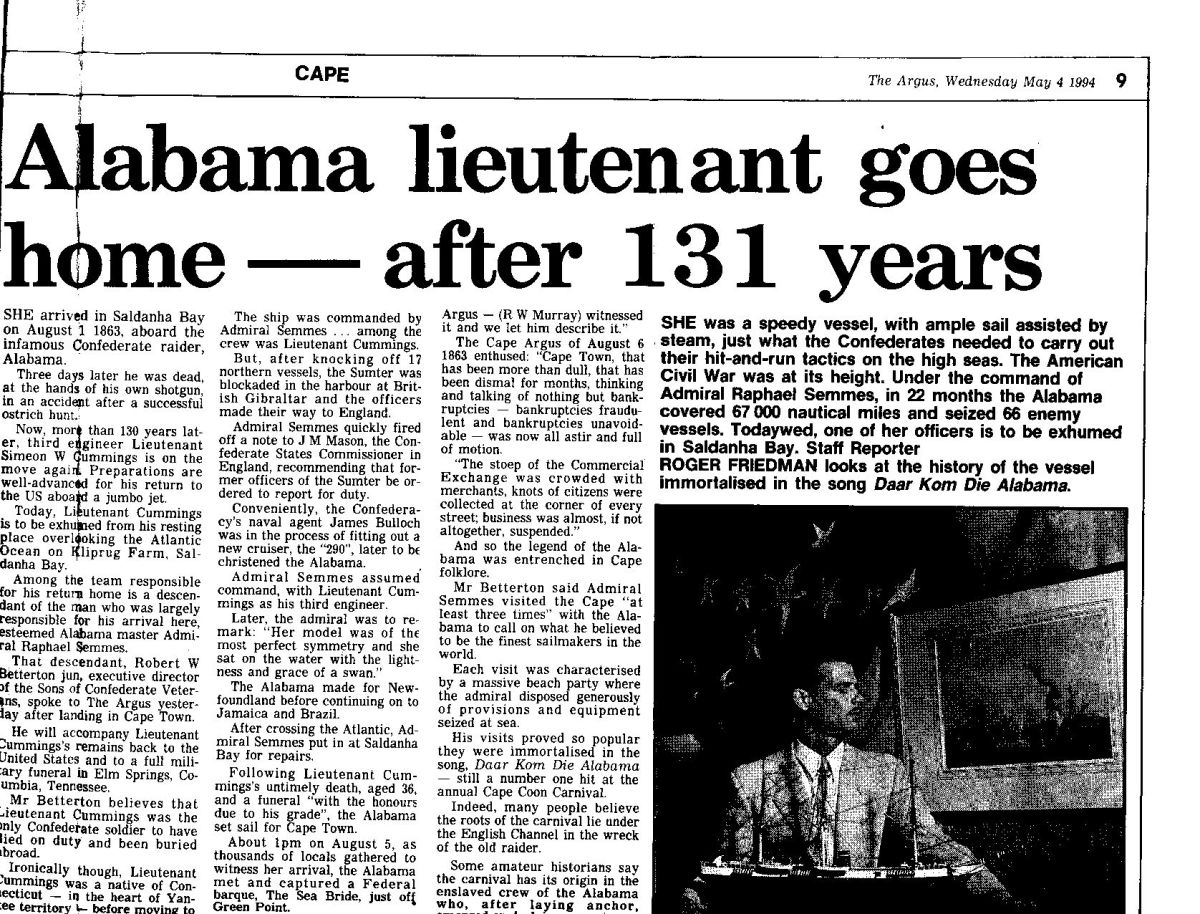

District Six and Coon Carnival

The carnival is the more visible, “touristy” aspect of Cape culture with its virtual “takeover” of the city in late December and early January each year. Troupes of what are known as “Klopse” (possibly a corruption of the word “clubs”) invade the city dressed in colourful costumes and making music on all kinds of portable instruments in marching bands which compete with each other.

In the days of apartheid this tradition was almost exterminated by the dour officialdom of “separate development” and the application of the Group Areas Act which led to the destruction of District Six, the cultural heart and home of the “Klopse”.

A brief summary of the history of District Six is given on the homepage of the District Six Museum (http://www.districtsix.co.za/frames.htm):

District Six was named the Sixth Municipal District of Cape Town in 1867. Originally established as a mixed community of freed slaves, merchants, artisans, labourers and immigrants, District Six was a vibrant centre with close links to the city and the port. By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, the history of removals and marginalisation had begun.

The first to be 'resettled' were black South Africans, forcibly displaced from the District in 1901. As the more prosperous moved away to the suburbs, the area became the neglected ward of Cape Town.

In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60 000 people were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as the Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers.

This happened in other parts of South Africa, of course, such as the destruction of that other cultural “hotspot”, Sophiatown, also known colloquially as “Kofifi” and “Soph’town”, in Johannesburg.

For the people of District Six, Martin writes,

“Forced removals were a tragedy. Even though some families eventually settled in dwellings of a better quality than those they occupied in District Six, nothing could replace the sense of place and community that existed there. A social fabric was torn to rags, a community was destroyed.”

The years since then have been a struggle for the community and for the Coon tradition. The loss of community life for the people of District Six has led to the horrors of life in the far-flung areas of Manenberg and Mitchell’s Plain where they had to contend with unfamiliar surroundings and neighbours, and long trips to and from work. In Manenberg in particular the destruction of social cohesion led to violence fuelled by gangsterism, liquor and drugs.

The anger and hopelessness engendered by this destruction was eloquently captured by Tatamkhulu Afrika’s poem “Nothing’s Changed”:

District Six.

No board says it is:

but my feet know,

and my hands,

and the skin about my bones,

and the soft labouring of my lungs,

and the hot, white, inwards turning

anger of my eyes.

A turning point of sorts came exactly 30 years after the destruction of District Six when, on 1 January 1996, the democratically elected president of South Africa, Mr Nelson Mandela, attired in a Coon outfit, arrived by helicopter at Greenpoint Stadium to give the opening speech at the Carnival.

Martin concluded his book with these words: “If the dream of a rainbow carnival for future New Years materialises, it may well reflect the rainbow balls of slavery times, at long last transcending oppression, prejudice and separations.”

Kirstenbosch

At the other end of the social scale, so to speak, is the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, which has a direct link to Van Riebeeck, in that the remnant of a hedge of indigenous wild almond trees (Brabejum stellatifolium ) planted by him is still to be seen there. This hedge was planted by Van Riebeeck in 1660 as a boundary between the colony and the indigenous inhabitants. The wild almond is in fact a relative of South Africa’s national flower, the protea, and its nuts resemble the Australian Macadamia nut. According to the Kirstenbosch website “The nuts contain cyanide and are not edible unless specially treated by soaking and roasting, a technique discovered by the early Khoi inhabitants.”

Kirstenbosch was founded in 1913 on land bequeathed to the nation by arch-capitalist and colonialist Cecil John Rhodes. The garden was started to specifically protect and grow indigenous plants, the first botanical garden in the world to have this goal.

The garden was started by Cambridge University botanist Henry Harold Pearson who had come to the Cape in 1903 to be Professor of Botany at the then South African College, which is today the University of Cape Town. In 1911 Pearson visited the land bequeathed by Rhodes to assess its suitability as a botanical garden. The government of the colony proclaimed the garden in 1913.

The garden is a wonderful place with many attractive features which make it popular with both tourists and local residents. From the garden there is a route up Table Mountain via Skeleton Gorge, which was popular with the then Prime Minister of South Africa Jan Christiaan Smuts.

Poet Alan James, in his poem “Cape Town: Spring” from “Two Poems in Botanical Gardens” (in the collection Ferry to Robben Island , Durban: Eyeball Press, 1996) writes

A secular world of objects that presents

Itself to the senses unremittingly,

Obstinately

Objects that tap leaves together patiently,

Repeatedly

Insistent signifieds that body and they

Figure, that evince, voice their

Classifications, Linnaean

Significations.

The final stanza of this poem:

And a man who looks about:

Who wanders uncertainly, not sure of his

Route, his right:

Who walks among the bellying shrubs, bushes

That sing chest-medalled, stays

A while, then goes, clutching

His ticket.

In another poem inspired by Kirstenbosch, from his 1992 collection Morning Near Genadendal, which was awarded the 1995 Olive Schreiner Prize for Poetry, James wrote:

An

amplitude of stillness and wholeness

stands about, invests the mountain,

the gardens, the innocuous-looking

suburbs too far away for

us to hear their alarms,

determine the reasons for smoke:

a pressure, a relationship to

be accepted even if not

measurable...

Politics and poetry

A city with such a rich cultural mix must also have a rich, complex political history and contemporary life. Cape Town indeed has a long history of social and political contestation which was intensified during the years of apartheid, that system legislated in the Houses of Parliament in the Avenue near the Company Gardens. The Anglican St George’s Cathedral at the top of Adderley Street, because of its proximity to Parliament, was often a site of protest, as was Greenmarket Square, as noted above.

Just across the Bay is the low mass of Robben Island, symbol of struggle and oppression for many, many years. In the midst of the beauty and majesty of its natural setting, the ugly face of politics is never far from consciousness.

Because of the many cultural, racial, religious and social threads that come together to make the multicoloured tapestry of the Cape so interesting, there is also a constant undercurrent of tension, of something that won’t be buried, can’t be buried by the surface beauty. It’s a shadow presence that works to keep one awake, alert.

It’s so very easy to be seduced by the white sands, the bracing waters of the western seaboard and the lazy beaches of False Bay, and yet one is constantly reminded that there is another aspect to the Cape, a dark side to it that cannot be erased. The reminders come at one like the cold, damp northwester that blows in winter, turning umbrellas inside out, lashing the seas into frantic sprays and the roads into glistening, treacherous ribbons.

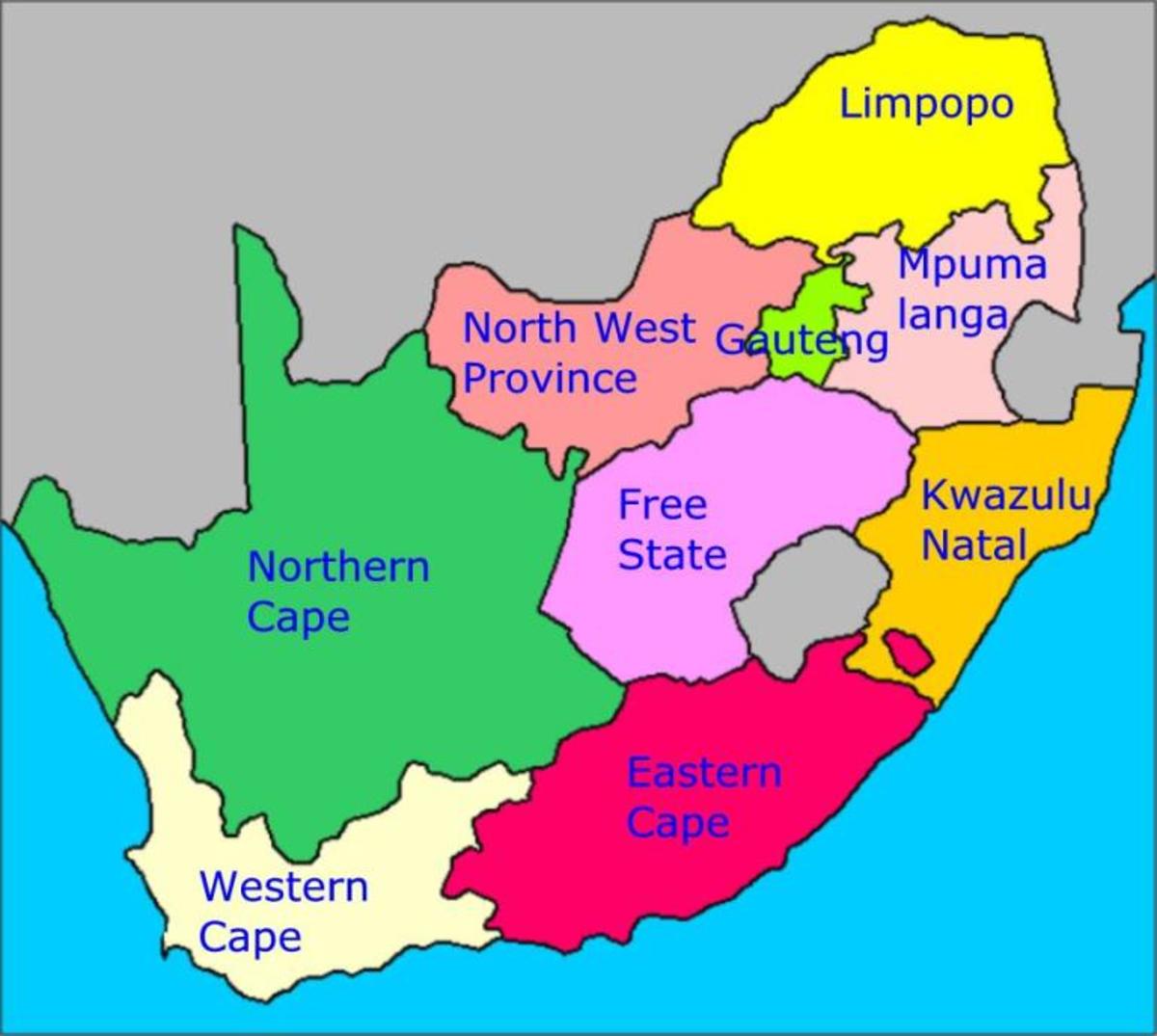

When the police in March 1960 shot and killed 69 people at Sharpeville, in what is now the Gauteng Province, during protests against the hated “Pass Laws”, similar events took place in Cape Town. A peaceful march on Parliament, by tens of thousands of people from Langa and Nyanga, was led by a young man Philip Kgosana. The police fired on protesters in the townships of Langa and Nyanga. A child was killed, shot dead in its mother’s arms. Great Afrikaans poet Ingrid Jonker was so moved by this incident that she wrote a poem then which was quoted by Nelson Mandela in his speech at the opening of the first democratically elected parliament of South Africa 34 years later.

Mandela said:

“In the midst of despair, she (Jonker) celebrated hope. Confronted by death, she asserted the beauty of life.

“In the dark days when all seemed hopeless in our country, when many refused to hear her resonant voice, she took her own life.

“To her, and others like her, we owe a debt to life itself. To her, and others like her, a commitment to the poor, the oppressed, the wretched and the despised.

“In the aftermath of the massacre at the anti-pass demonstration inSharpeville, she wrote:

‘The child is not dead...’”

The title of the poem: "Die kind wat doodgeskiet is deur soldate by Nyanga (The child who was shot dead by soldiers in Nyanga)". The final stanza reads:

Die kind is die skaduwee van die soldate

op wag met gewere sarasene en knuppels

die kind is teenwoordig by alle vergaderings en wetgewings

die kind loer deur die vensters van huise en in die harte van moeders

die kind wat net wou speel in die son by Nyanga is orals

die kind wat n man geword het trek deur die ganse Afrika

die kind wat n reus geword het reis deur die hele wereld

sonder n pas

This poem has been translated by Antjie Krog and Andre Brink, published in the collection Black Butterflies (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 2007). That beautiful final stanza reads in this translation (note: a Saracen was a South African armed personnel carrier frequently used by the army and police in “riot control” actions at that time):

The child is the shadow of the soldiers

on guard with guns saracens and batons

the child is present at all meetings and legislations

the child peeps through the windows of houses and into the hearts of mothers

the child who just wanted to play in the sun at Nyanga is everywhere

the child who became a man treks through all of Africa

the child who became a giant travels through the whole world

Without a pass

Ingrid Jonker wrote in an article in Drum magazine in May 1963: “I am surprised when people call it (the poem) political. It grew out of my own experiences and sense of bereavement. It rests on a foundation of all philosophy, a certain belief in ‘life eternal’, a belief that nothing is ever wholly lost.”

Jonker committed suicide by walking into the sea at Three Anchor Bay in July 1965:

Korreltjie klein is my woord

korreltjie niks is my dood

(Small grain of sand is my word, my breath

small grain of sand is my death)

- From the poem “Korreltjie sand (Little grain of sand)”

Table Mountain

The most famous and recognisable feature of Cape Town is, of course, the mountain. No-one I think can see this magnificent mountain and not be moved. I have been to the top of the mountain many times, by Skeleton Gorge, by Platteklip, by the Bridle Path and by the cable car. Whatever route or means I have taken the place has been magical to me and I never tire of it.

The first European to climb the mountain as far as we know was Portuguese Admiral António de Saldanha who did so in 1503. He had sailed into Table Bay and was not sure whether or not he had rounded the Cape of Storms and so climbed the mountain to check. He gave the mountain its name and carved a cross on a rock on Lion’s Head. The indigenes had called the mountain Hoerikwaggo, which means “Sea Mountain.”

Five dams were built on Table Mountain in the late 19th Century to supply water to Cape Town. These dams are no longer part of the city’s water supply.

The cableway was first opened in 1929 and extensively refurbished in 1997.

A stylised graphic of the mountain serves as a sort of logo for the City of Cape Town.

The mountain has for centuries since Camoes’ time inspired artists, writers and poets. Noted writer Antjie Krog, wrote “four seasonal observations of Table Mountain” that were published in her 2006 collection Body Bereft, which at the time had some moments of notoriety due to its cover which showed the naked breasts of an older woman (Cape Town: Umuzi).

Part of the autumnal observation, titled "Sunday 10 may", reads:

I try to ponder you: rock

hard, stone cold, everlastingly

aloof in

muted matting casings

until the

mass of umbrella pines fall

from scale, the foghorn moans

your absence into apprehension

that where you

are will ultimately

be one great

void.

Copyright notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2010