Cassava and How a Poisonous Plant Conquered Humans

One of the most important crops in the world

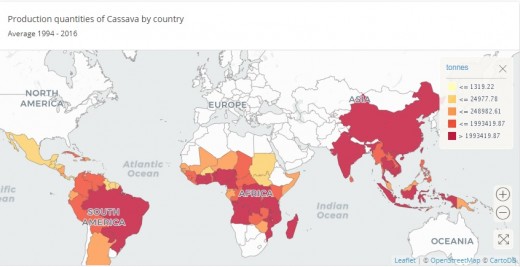

Of all the plants in the Americas, cassava or manioc, Manihot esculenta Crantz, is indeed the only one that competes with potatoes and maize in terms of importance in the traditional native diets of Central and South America. In fact, it is the third largest source of carbohydrates in the tropics, after rice and maize, and one of the main staple foods in the developing world, existing in the basic diet of more than 500 million people worldwide. Nonetheless, it is a peculiar choice that among the so many plant species that can be considered food, Central and South Amerindians preferred just one of the most poisonous. All varieties of cassava have a high content of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) ranging from 15 to 400 mg/kg of cassava. This poison, also known as prussic acid and long known to humanity, saw its popularity rise to unimaginable levels as it was one of the Nazis favourite weapons, used not only in the gas chambers to annihilate Jews but also as their last escape. The varieties of cassava with the highest poison content can only be consumed after previous processing to remove hydrogen cyanide. This processing is rather laborious, and only a few varieties known under the general name of sweet cassava can be consumed after a simpler processing such as cooking.

10,000 years ago

From the earliest days of domestication, a distinction has already been made between poisonous and “non-poisonous” types of cassava; being the “non-poisonous”, i.e. the least poisonous that would require simpler processing, simply called sweet cassava as opposed to the poisonous ones called wild type. This distinction even led these plants to be classified as distinct species. However, nowadays it is known that the morphological characteristics of both groups are exactly the same belonging to one single species Manihot esculenta Crantz, being different in the hydrogen cyanide content only. The toxicity of cassava is not totally intrinsic rather it is also affected by environmental conditions in which the plant grows, so that the content of hydrogen cyanide may change for the same plant variety growing in different locations. Cassava is a shrub belonging to the spurge family Euphorbiaceae, with its most famous members being the Pará rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) and castorbean (Ricinus communis L.). It is thought that cassava originated in the more remote forests of western Brazil (southwest of the Amazon), where it must have domesticated and selected about 10,000 years ago. Before the arrival of Europeans to America, cassava had already been disseminated, as a food crop, northwards up to Mesoamerica (Guatemala and Mexico). It is one of the most drought-tolerant crops, capable of growing on marginal soils. The oldest direct evidence of cassava cultivation comes from a 1,400-year-old Maya site, Joya de Cerén, in El Salvador.

Amazon Origin of Cassava

Edible but deadly

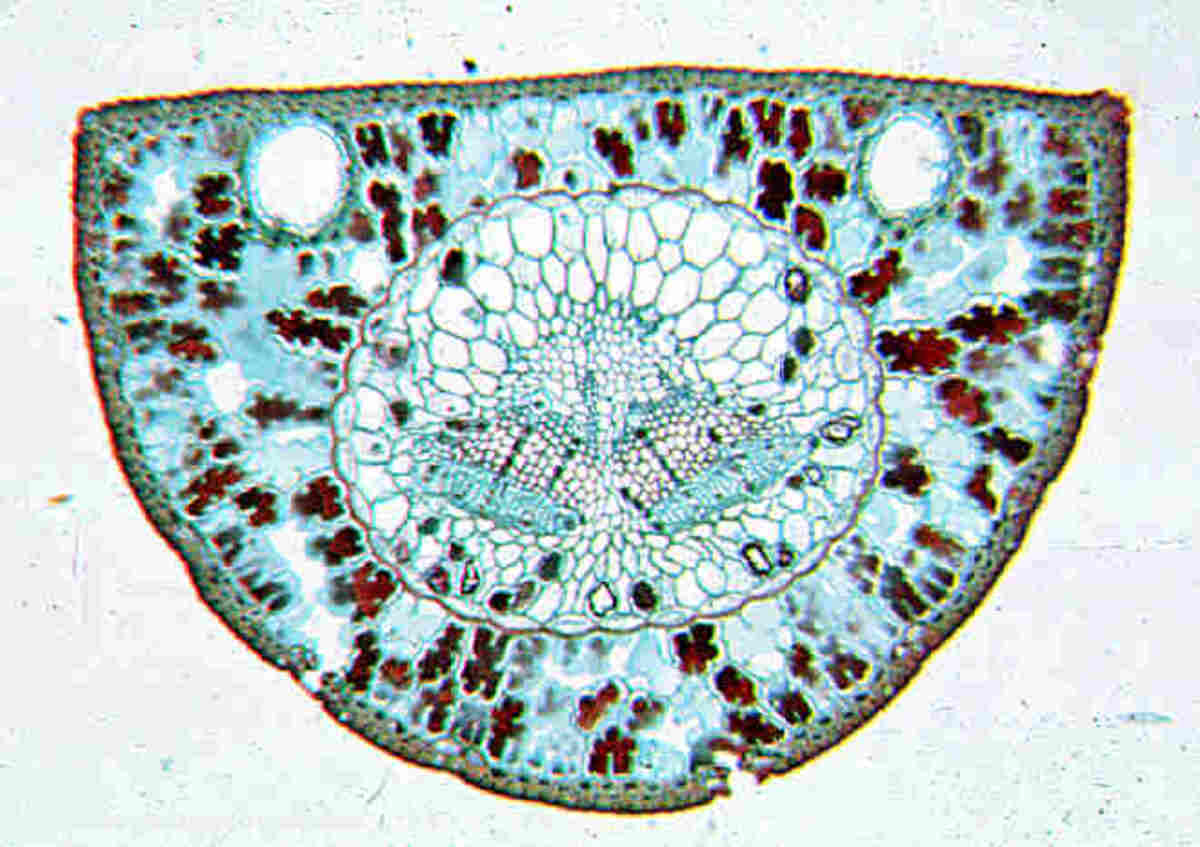

The cassava root is long and tapered, up to 30 cm long, with a firm, homogeneous chalk-white or yellowish flesh enclosed in a detachable rough brown rind. Cassava root is a typical adaption to drought or transient periods of water stress shown by some plant species, being very rich in water, starch, with small amounts of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin C, but poor in protein and other nutrients. What makes cassava poisonous is a precursor of hydrogen cyanide called linamarin, a cyanogenic derivative of glucose (glycoside), which is broken down by an enzyme present in the plant itself, linamarase. This results in the release, among other substances, of hydrogen cyanide. In the bloodstream of many animals, the hydrogen cyanide releases the cyanide ion, CN-, which is then transported by hemoglobin instead of oxygen. Once reaching the cells, cyanide binds strongly to the mitochondrial cytochrome, which is responsible for the transport of electrons in the cellular respiration, stopping cellular respiration leading to cell asphyxiation and depending on the amount of cyanide in the blood, to death. Linamarin is found in the leaves and roots of many plants such as cassava, lima beans, flax, apple, oats, wheat, rye and sugar cane. However, cassava is the only one that presents the linamarin in its edible parts. Other plant species, like almonds, apricot, peach, and plum, for example, present other cyanogenic glycosides, amygdalin, in its seeds (kernels).

Giving a poisonous plant such a prominent role in a population's diet seems to be nonsense, but the fact is that the Central and South Amerindian cultures have evolved to accept the importance of this plant species. Therefore, a series of methods and instruments (e.g. graters, roasters, and sieves) were created to facilitate the processing of cassava and in Brazil the cultural organization of native populations was deeply influenced by the cultivation of cassava. For example, the heavy workload that comes from processing this plant was the sole task of women. The tipiti is a native Brazilian instrument inspired on the body of the snake Boa constrictor. Its invention by South American Amerindians is a very interesting example of how human culture advances in order to adapt to the surrounding environment. The tipiti is made of finely woven palm leaves that can be widely widened to receive the cassava paste and then separate water (juice), containing linamarin, from starch, both accumulated in the plant’s root, thus allowing cassava to be consumed.

Life around cassava

One of the innumerous indigenous legends dealing with the origin of cassava was reported in 1876 by Couto de Magalhães (a Brazilian politician, military, writer, and folklorist): “In olden times the daughter of a very important village chief who lived in the vicinity of today’s city of Santarém, in the state of Pará, at the very heart of the Amazon forest, appeared pregnant to her family and all the village surprise. The chief wanted to punish the offender who dishonored his daughter and demanded to know who he was. He threatened her with severe punishments. However, nothing worked as the young woman remained adamant, saying that she had never had any kind of relationship with any man. Having all his efforts made in vain, the chief had made up his mind about sentencing her to death, thus serving as an example to all other women who would dare to follow his daughter. Not so long before the scheduled ritual ceremony, a white man appeared to the chief in a dream, telling him to spare his daughter’s life, for she was indeed innocent and had no relationship with any man. The chief relinquished his initial orders and followed his dream. After nine months, the chief’s daughter gave birth to a beautiful and white baby girl, which caused great surprise not only to her local tribe but also to all neighboring villages. News spread fast and people traveled long distances to visit the white immaculate child believed to be special and of a new race. However, the child, named Mani, being precocious by starting to walk and talk far earlier than anyone has ever seen died just after a year, without ever becoming ill or showing any signs of pain. She was buried inside the family house and her grave was cared for and watered daily, according to local tradition. After a while, an unknown plant emerged from the grave and due to its novelty and appearance, people did not pluck it as they did to the other plants that grew on the infant’s grave. The plant grew, flourished, flowered and finally bore fruit. Birds that ate its fruits became intoxicated, and this phenomenon, unknown to the local population, increased its suspicions about the new plant. One day the earth cracked and people dug it recognizing the plant’s white immaculate root as the body of little Mani. They ate it and from then on they learned how to cultivate and use cassava.”

Having in mind the limited knowledge of native southern Amerindian populations about plant development and physiology, it is still worthy of note some interesting elements in this story. Mainly because one can identify in it some facts of cassava’s physiology and development, although one must not forget the context and time at which these stories were created. Note that the chief's daughter becomes pregnant without having sex. Oddly enough, there are two characteristics of cassava that can be directly related to this part of the story. First, cassava, as many other plant species, is a plant that propagates vegetatively; that is, it can grow from root or stem cuttings. In addition, cassava has the incredible ability to generate seed without being fertilized, in a very intriguing process known as apomixis (asexual reproduction) through parthenogenesis. It is very difficult to believe that southern Amerindians of the Amazon basin had knowledge of apomixis. However, they obviously knew plant vegetative propagation, so that it is possible this story, as many other similar ones about plants, was elaborated with this in mind. Also, the story tells us that birds that ate its fruits got drunk. It is possible that this refers to the toxic properties, namely the presence of hydrogen cyanide, in this plant.

The advantages of being poisonous

It is really interesting that some people selected a highly poisonous plant for their food. Even more interesting is that, having the option for varieties with less poison content, the poisonous ones are favoured. In fact, wild cassava is widely cultivated not only by native people in Brazil’s inland, but also by some farmers. They prefer the most poisonous varieties. In a study made with the Tukanoans in northern Amazon, it was found that although they had access to less poisonous varieties of cassava, 90% of their cultivation was poisonous plants against only 10% of the so-called “sweet” varieties. One must not forget that the processing necessary to remove the hydrogen cyanide from cassava is very laborious, and apparently it would be a gift to have varieties almost without any poison. However, cassava is possibly the only food in the world that has been consciously selected to favour more toxic cultivars over other less toxic. In order to understand why this happened, a group of researchers from the New York Botanical Garden compared the yield of wild (more poisonous) and sweet cassava cultivars, and came to a conclusion that explains why such preference. Wild cassava varieties have generally higher yield than sweet varieties. In addition, another characteristic that may help us understand such peculiar choice is that in an environment full of pests and herbivores venomous varieties show higher productivity as hydrogen cyanide is highly toxic to virtually all living things. Thus, by protecting the plant against herbivores and other pests, including thieves, it allows it to develop more than sweeter varieties facing similar threats. This fact makes even more sense if one imagine these populations living in environments with limited knowledge or access to modern methods of plant protection. Therefore, for these populations using nature’s own means to protect the plant seems to be a sensible way of living and competing in such adverse conditions, even if there is a higher price to pay in getting food, in these case getting rid of cyanide. In fact, studies conducted with the other cyanogenic plant species, e.g. white clover (Trifolium repens), bird's-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) and alpine bird's-foot trefoil (Lotus alpinus) have shown that many animals avoid consuming the most poisonous varieties.

How it became global

As with many discovered or introduced plant species by Europeans while making their first efforts to globalization, the Spaniards and the Portuguese in their early occupation of the Americas had all sorts of prejudices against cassava. In this respect, Spaniards were particularly keen on keeping theirs. In fact, it took them longer to be convinced of the nutritious features of cassava as they thought it, like they did with maize, insubstantial, dangerous, damaging to Europeans and not nutritious. Also, and possibly the worst thing, was that at the eyes of these Christians in the New World, cassava was not suitable for communion since it could not undergo transubstantiation and become the body of Christ. Nonetheless, the cultivation and consumption of cassava was continued in both Portuguese and Spanish America. However, wheat, and any cereal for that matter, could not be grown under the tropical weather in the Caribbean islands. Thus, facing the dilemma of how to best feed the crews of their ships while traveling back and forth to Europe in journeys that would take months, Spaniards finally surrender to being practical, after all native Americans lived by eating cassava. The first mass production of cassava bread was established in Cuba to supply the Spanish ships departing to Europe from Cuban ports, such as Havana, carrying goods to Spain. In this respect, cassava had another advantage as its bread would not go stale as quickly as regular cereal bread, although it did not prevent sailors from complaining that it caused them digestive problems. The Portuguese seemed to be more pragmatic earlier than their Christian brothers as they introduced cassava into Africa, and later Asia, from Brazil in the 16th century. As with maize, cassava is now an important staple foods replacing native African crops and for that reason it is sometimes called as the “bread of the tropics”.

You might also find useful to read:

- The Long and Troubled Voyage of Sugar: from the Idyl...

Sugar has long been known to man. However, sugar as we know it was only made around 400 AD and its industrialization occured much later in the sixteenth century. Here is a description of its long and troubled voyage from 8000 BC to our tables. Once c - The Old and Intriguing History of Maize

Before becoming today's most important crop in world, maize had a long and troubled voyage that started centuries ago. It had a dark secret in it that may have inspired one of the most popular novels. - Tobacco: The Incredible Journey of a Notorious Kille...

The Age of Discovery, initiated in the fifteen century, introduced many plant species to many different regions throughout the world. Some plant species changed society and economy dramatically and their effects are still present. Here is the story o - Chocolate: The Aztec Treasure that Became Global

Once a treasure very well kept Aztecs, cacao made a long journey from its native Amazon forest to our cups and cakes. Used as currency in Central America, and served as beverage to Aztec royalty, it was then sweetened by Spaniards who created chocola - Plants and Portuguese Discoveries: How Americans Got...

Many of our most useful, tasteful and favourite food and plants have made a long journey to reach our tables at home. That journey began long ago and some of those plants changed European and Asian societies dramatically. Know more about how and why